Silicon Valley’s legendary status as the birthplace of innovation isn’t merely a product of geography or luck — it is rooted in a culture of creative destruction, a term popularized by Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter, author of Theory of Economic Development. Creative destruction is the process by which innovation disrupts existing industries, rendering outdated systems obsolete while paving the way for new growth. In Silicon Valley, this ethos isn’t just a byproduct of progress; it’s a philosophy that has been intentionally nurtured, celebrated, and refined.

The seeds of creative destruction in Silicon Valley were planted long before it became synonymous with the tech industry. In the mid-20th century, the region’s proximity to Stanford University and defense contracts during World War II fostered a symbiotic relationship between academia, industry, and government. I’ve asserted that the underpinning of Silicon Valley draws from WAY before that though, in the counterculture of Haight-Ashbury and even earlier, the creative destruction of fashion thanks to a man named Levi Strauss.

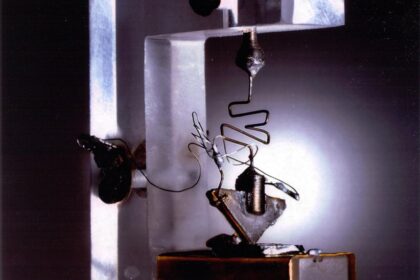

Still, in tech, pioneering figures like William Shockley, one of the inventors of the transistor, brought cutting-edge research to the area, attracting talent and funding. When Shockley’s management style alienated some of his brightest employees, the infamous “Traitorous Eight” left to form Fairchild Semiconductor—a bold act of defiance that epitomizes the Valley’s embrace of reinvention and risk-taking.

This pattern repeated itself as Fairchild became the incubator for numerous other companies, including Intel. The willingness to challenge authority and strike out on one’s own became an unspoken rule of the game. Silicon Valley didn’t just accept creative destruction; it institutionalized it.

In the words of Mark Suster, entrepreneur and venture capitalist, “Great entrepreneurs don’t fall in love with their solution. They fall in love with the problem they’re solving.” This mindset is foundational to creative destruction—it’s about building something new not for the sake of novelty, but because the status quo is no longer adequate.

The Role of Venture Capital in Reinventing Industries

Central to the Valley’s culture of creative destruction is its robust venture capital ecosystem. Firms like Sequoia Capital and Andreessen Horowitz don’t just invest in ideas—they invest in disruption. These investors understand that failure is not a bug of the system; it’s a feature. The appetite for risk, and the willingness to back founders who may fail before they succeed, has fueled a cycle of relentless innovation.

Fred Wilson, a partner at Union Square Ventures, captured this spirit when he said, “Invention requires a long-term willingness to be misunderstood.” Venture capitalists in Silicon Valley are betting not just on technologies, but on the unorthodox, contrarian thinkers who are willing to challenge prevailing norms. This creates an environment where failure is not just tolerated—it’s often a badge of honor, signaling that someone has dared to test the limits of what’s possible.

Positive Destruction

While the term “destruction” carries a negative connotation, Silicon Valley has demonstrated time and again that the process is overwhelmingly positive. Consider the demise of physical media like DVDs and CDs. Streaming platforms such as Netflix and Spotify have emerged not just as alternatives, but as superior solutions that democratize access to entertainment. The same is true for industries like retail, where the rise of e-commerce giants like Amazon has redefined how we shop.

What makes Silicon Valley somewhat unique is its ability to see opportunity in upheaval. By dismantling entrenched systems, new possibilities emerge, often leading to increased efficiency, broader access, and the creation of entirely new markets. The gig economy, for example, has empowered millions of individuals to work on their terms—something inconceivable just a few decades ago.

At its core, Silicon Valley’s culture of creative destruction thrives on a shared understanding that the future cannot be built by clinging to the past. This principle is evident in the region’s acceptance of rapid cycles of innovation. Steve Jobs famously declared, “Innovation distinguishes between a leader and a follower,” underscoring the Valley’s relentless pursuit of what’s next.

Not without its challenges, disruption inevitably leads to displacement, as industries adapt and workers retrain for new roles; this is often painful, difficult, and even fails. Yet Silicon Valley’s enduring optimism has reframed these challenges as opportunities. Initiatives like the burgeoning “upskilling” movement aim to equip workers with the tools they need to thrive in a rapidly changing landscape.

In this sense, Silicon Valley offers a blueprint other startup ecosystems should study. It’s not about tearing things down for the sake of destruction; it’s about rebuilding something better. By viewing disruption as an opportunity rather than a threat, the Valley has not only survived but thrived, becoming the world’s most influential hub of innovation.

The lesson? If you want to build the future, you can’t be afraid to challenge the present. That, in essence, is the magic of Silicon Valley: its ability to turn the chaos of creative destruction into something golden.

Amazing to find Schumpeter in a LinkedIn article in 2025, decades after my thesis on innovation management quoted him literally in the first sentence — Great article, Paul O’Brien!

Love this part of your reflections, Professor O’Brien: “In this sense, Silicon Valley offers a blueprint other startup ecosystems should study. It’s not about tearing things down for the sake of destruction; it’s about rebuilding something better. By viewing disruption as an opportunity rather than a threat, the Valley has not only survived but thrived, becoming the world’s most influential hub of innovation.”

Trevor Jeyaraj re: ” it’s about rebuilding something better.”

“…it’s about rebuilding something better, *as defined by the market*”.

Remember the .com boom and bust? Most of the bust wanted to disrupt something in way that no one cared. about. Had Netflix skipped DVDs and went right to streaming would they have survived?

In a different way, remember the iPod? Apple didn’t invent the MP3 player. There were plenty of those. What it did do was give the public an easy and legit way to buy music. More importantly, it gave the then-desperate music industry (i.e., another market) a way to maybe save itself**. The hardware wasn’t new per se but the model and the markets were. That said, could a startup have gotten the music industry’s attention and buy-in then? Probably not. It had to an Inc on the order of Apple.

** The dirty little secret here is Jobs & Co sold tons of hardware on the backs of (starving) artists. 99 cents was a loss leader. Apple effectively turned music studios into sweatshops for all but the biggest artists. Thanks Steve?

Revenge of the Nerds.

I wish Houston had this spirit. I know I do, but I feel like I’m speaking in the wind and that no one hears it …

The instant we become satisfied with the status quo, we’ve lost. Complacency is the enemy. Always enjoy your reflections Paul O’Brien and I hope you’re well!

Capitalism drives creative destruction, only governments and regulation slow it down.

Steve Jennis article pondering something similar getting published soon