Article Highlights

Entrepreneurial DNA: The Science in Startup Success

The mythology of entrepreneurship has always been convenient for investors and romantic for founders: anyone with grit, an idea, and caffeine can succeed. But data is increasingly cutting through the myth. A growing body of research confirms that personality traits, psychological wiring, and the composition of the founding team are among the most consistent predictors of startup success or failure.

That shouldn’t be surprising. Startups are not small businesses; they’re high-variance experiments in markets where 90% fail. What tips the balance between survival and collapse is rarely a spreadsheet (though, ironically, I’m going to give you a spreadsheet I’ve been playing with). It’s the behavior of people under uncertainty: how they react to setbacks, how they make decisions with incomplete information, and whether they can persuade others to follow them when the plan looks insane.

The question for founders and investors is no longer whether these traits matter, it’s how to measure them, how to build teams that complement them, and how to de-risk ventures by paying attention to Entrepreneurial DNA.

What the Research Shows

In October 2023, a research team at the University of New South Wales published a landmark study in Nature Human Behaviour. The conclusion was blunt: founders are distinct in personality from the general population, and those differences strongly predict startup outcomes. Successful entrepreneurs consistently exhibited higher levels of novelty-seeking, resilience, energy, and social vitality.

A 2022 systematic literature review in Frontiers in Psychology analyzed decades of entrepreneurial research and found five traits that most reliably predict entrepreneurial intention and performance:

- Self-efficacy – the belief in one’s ability to execute and achieve.

- Conscientiousness – being organized, disciplined, and persistent.

- Locus of control – believing outcomes depend on one’s own actions, not chance.

- Innovativeness – willingness to generate and try new ideas.

- Need for achievement – motivation to meet and exceed challenging goals.

Classic meta-analyses of the Big Five personality traits (Zhao & Seibert, 2006, Journal of Applied Psychology) reinforce this: entrepreneurs tend to score high on openness to experience and conscientiousness, somewhat lower on agreeableness, and significantly lower on neuroticism. In practical terms: they thrive on novelty, manage tasks rigorously, are willing to challenge norms, and don’t fold under pressure.

Perhaps most importantly, a 2023 large-scale analysis of startup teams showed that personality diversity among co-founders increases survival rates and growth trajectories. Teams where all founders shared the same traits – say, three visionaries with no detail-oriented executor – fared worse than heterogeneous teams with complementary wiring.

I covered this years ago when work was increasingly published and Oxford rolled out their assessment of the need variety and novelty, reduced modesty, an openness to adventure, and heightened energy levels among founders, correlating those qualities with an exceptionally higher rate of success.

The implication is clear: you don’t need to be everything yourself (you can’t be) – but your team collectively does.

The opportunity is less well known: for more than a decade, the assessment of entrepreneurs has been readily available and ideal to idea stage entrepreneurs, all through a partner every startup ecosystem should have in place to identify and develop local entrepreneurs.

Entrepreneur DNA Assessment

Unlike legacy personality frameworks built for corporate HR (Myers-Briggs, DISC), both of which are meaningful, an assessment you all should using or providing was designed specifically to measure the behavioral traits that matter in entrepreneurial contexts.

The methodology draws on over 100,000 data points from founders worldwide, tracking which traits correlate with persistence through acceleration programs, venture creation, and fundraising outcomes. The assessment is structured across 25 dimensions of entrepreneurial potential.

The Dimensions of Entrepreneurial DNA

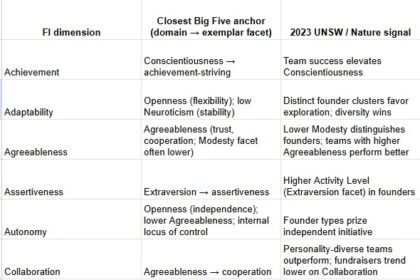

As I dug into the 25 Dimensions of Entrepreneurial DNA that Founder Institute developed, my MBTI-wired brain couldn’t help but notice that the varied research reinforces a few of the same qualities that all but determine success or struggle.

Some of the dimensions I’ve assessed can be grouped into categories that map directly to validated research:

- Self-Belief and Drive

- Self-efficacy

- Need for achievement

- Internal locus of control

- Execution and Grit

- Conscientiousness

- Perseverance

- Time management

- Stress tolerance

- Innovation and Creativity

- Openness to new experiences

- Ideation ability

- Problem-solving flexibility

- Risk and Adaptability

- Risk tolerance

- Ambiguity acceptance

- Resilience after failure

- Social and Leadership Capital

- Persuasiveness

- Networking ability

- Leadership presence

- Empathy and team orientation

- Pragmatism and Market Focus

- Customer orientation

- Learning agility

- Decision-making speed

These categories are not arbitrary; they overlay tightly with the peer-reviewed literature. This assessment is operationalizing research for startup contexts and while communities, startup development organizations, and universities continue encouraging entrepreneurship without this assessment in place, they’re effectively fostering failure by neglecting what might be the only sound science we have into what makes startups successful.

The Four Entrepreneur Types

This assessment clusters founders into broad “types” based on their dominant patterns. Typically, framed Visionary, Builder, Optimizer, or Strategist, the principle is that different founders succeed in different environments. This is why, I surmise, we have different types of founders defending their potential despite some personality assessments while we also find the ideal entrepreneurs failing despite having the right qualities. In the work you’re doing, deciding that someone is an entrepreneur isn’t sufficient to helping everyone succeed; your work can do so much more – developing the various circumstances (environments) in which different types thrive:

- Visionary Innovators thrive in novel, uncertain markets but often need execution-driven co-founders.

- Disciplined Executors keep the trains running but may under-invest in risk-taking.

- Social Mobilizers excel at persuasion and team-building but need partners strong in technical rigor.

- Pragmatic Optimizers scale existing models effectively but may resist radical innovation.

Again, research supports this segmentation. A 2023 UNSW study identified similar archetypes (novelty-seekers, exuberant initiators, disciplined operators) showing that startups with coverage across these archetypes had significantly higher performance.

And hopefully you can see yourself in a more or less ideal environment, if you’ve taken Founder Institute’s Assessment or at least evaluated your personality with one of the more broadly applicable evaluations. I find myself comfortable in environments where I can thrive being a Social Mobilizer or Visionary Innovator but burden me with existing models that resist change (where Pragmatic Optimizers excel). And notice, founders or cities, the deeper dive into Entrepreneurial DNA that partnering with Founder Institute provides, guides how to help startups develop the right teams – as a Social Mobilizer, someone like me needs a partner strong in technical rigor. Knowing this, and telling founders, isn’t criticism, it’s the meaningful advice that entrepreneurs are clamoring for among the noise of people yelling “Product Market Fit” and “CAC.”

Comparing Methodologies

I’ve referred to the more well-known evaluations so let’s compare a bit with familiar frameworks:

- DISC helps explain communication styles, but it has limited predictive validity for entrepreneurial outcomes.

- Myers-Briggs (MBTI) is popular in corporate environments, but psychologists rightly critique the inaccuracy of the countless *test* that people have created to capture your information (for years, I thought I was an ENTJ until I put more rigor into knowing myself). It can be a useful conversation starter but not a predictor of success if it’s wrong.

- Rocket Fuel’s Visionary/Integrator model (Gino Wickman) offers a practical lens for pairing leadership roles but might simplify the founder’s psychology too much into a binary.

What the Entrepreneur DNA Assessment contributes is specificity: it measures exactly the traits most correlated with starting and scaling ventures, validated against outcomes. It doesn’t replace other tools, but it provides a more predictive base for founder development and team design.

For Founders AND Investors

Knowing your profile allows you to be intentional about co-founder selection and personal growth. The right takeaway is not “you don’t have what it takes,” but “you may need to pair with someone who has what you lack.”

For investors: founder assessment is often intuitive and biased – and it certainly shouldn’t be when we have decades of data and research correlating personalities without comes. Seriously, what investor in their right mind would neglect having this data in place? An empirical model grounded in psychology reduces subjectivity. It provides a structured way to identify which founders are more likely to execute, which teams are complementary, and where risk mitigation is needed.

For ecosystems and policymakers: entrepreneurial training programs often over-index on business planning and fundraising. The evidence suggests they should also emphasize founder psychology – coaching self-efficacy, resilience, and team composition. In much of my personal passion and work, I want to see this in place in your community so stop considering it and reach out to me to get it there.

Entrepreneurial DNA is measurable, and it matters. Ignoring it is akin to ignoring burn rate or runway. The Founder Institute’s DNA Assessment is one of the few tools designed to operationalize this science for founders in the real world.

Taking the assessment is not about vanity. It is about data: where you thrive, where you falter, and where you need others. In a market where the failure rate hovers at 90%, that knowledge shouldn’t be optional – and failing to expect it or provide it so that entrepreneurs can optimize their start, is neglect.

Entrepreneurial personality traits strongly predict startup outcomes. The question is whether founders and investors will choose to measure them or continue relying on instinct and charisma.

If you’re building a company, start by understanding your own entrepreneurial DNA, take the assessment to have one empirically grounded way to do so. Then build deliberately: not just a product or market strategy, but a team whose combined traits tilt the odds in your favor.

It isn’t the idea that fails. It’s the team’s psychology that cracks first.

Oh the spreadsheet!

I’ve been mapping different assessments together – you see a glimpse of it in the spreadsheet image above. If you’re curious or would like to contribute, drop your email address by subscribing to my substack and I’ll get you added (if you’re already a subscriber, DM me)

Who are defining as entrepreneurs and startups in your data? Are you talking about investor-funded startups with very high potential, typically in the tech area? Or are you including the other 999 out of 1000 business owners who start most businesses that many call “small to midsize” businesses?

Great question, and important distinctions. In this analysis, “startup” follows Steve Blank’s definition: a startup is a temporary organization designed to search for a repeatable, scalable business model. That’s about stage and intent, not sector or funding; a scalable search can happen in biotech, beverages, or software, with or without venture capital. Small–midsize businesses are built to operate on known models from day one, valuable to the economy, but fundamentally different in risk, policy needs, and outcomes.

For context, policy and research bodies separate these categories, too. OECD and BLS define “high-growth” firms by performance (typically ?20% annualized growth over three years), which is a different population than the broader universe of small businesses. Kauffman’s growth entrepreneurship work likewise focuses on the minority of firms that scale employment and revenue rapidly, while Brookings notes that this high-growth slice is small but disproportionately impactful. My work uses the startup definition above, then looks at traits and team composition within that subset.

If it helps: I’ve also written on why conflating startups with small businesses leads to bad policy and bad expectations; useful background on why I draw the line where I do.

People have asked: “Are you worried someone will steal your idea?”

I’m like… absolutely not.

Because building a startup is the hardest sh*t ever.

It’s not about the idea. It’s about the drive to build and fearlessly execute when no one’s watching, no one’s clapping, and nothing’s working yet.

This post from Paul O’Brien nails it:

Success comes down to traits that can’t be faked.

For me, #1 is self-belief and drive.

I’ve always believed in myself. Almost crazily so.

(Thanks, Mom & Dad.)

Because I know I’ve got the grit.

I always plow through until I get where I want.

I get what I want because I make it a reality.

And I will relentlessly execute, forever.

I’m competitive with myself. I’m competitive with my co-founders.

“Work as if someone is working 24/7 to take it all away from you.” Mark Cuban

I’m doing that.

Shoutout to my ride or die co-founders Ben Brewer and Eric Davis.

I love this and I clearly agree with you on the substance – Ideas don’t win; people do. For clarity with readers who blur “small business” and “startup,” I use Steve Blank’s frame: a startup is a temporary organization searching for a repeatable, scalable model; not a smaller version of an existing business: https://steveblank.com/2010/01/25/whats-a-startup-first-principles/

Where I’d add (and where I think our worlds overlap Laura): psychology is necessary; the policy environment is decisive. Grit can still get kneecapped by procurement cycles, licensing and compliance burdens, and misaligned incentives. Your platform sits right at that fulcrum: government relations as the lever that reduces friction for the teams who already have the right DNA. That’s why Founder Institute built an assessment that founders and ecosystems can actually use to compose complementary teams and then tackle the right external constraints first.

We might explore the traits we’re seeing in successful ventures against specific policy bottlenecks, then publish a short, evidence-based brief that agencies and lobbyists can act on: procurement pathways, regulatory pilots, the stuff that measurably moves the needle for startups. I’ll DM

the difference between founders who make it and those who don’t? it’s exactly this… pushing through when logic says quit. paul’s right about that execution piece being everything.

Yup. Ideas without action aren’t worth the paper they’re written on. It’s all about execution and distribution Laura!

Would be good to see how an AI investment agent trained on this data would perform as a virtual VC. Not doubt some LPs are doing this (in stealth) to see if they can get better value for money than VCs offer.

Steve Jennis cc Joshua Sutton, CSPO…

I’ll send you both the spreadsheet if you want, LMK, I’m impressed at the implication of tying together the various assessments and studies.

Loved everything about Paul. Thanks for sharing

Love the deep insight!

The best part is that once you know your Entrepreneur DNA, you can work on improving your weaknesses and doubling down on your strengths

This is very analytical Paul and data is always important so you can be causative about your hires!

Susie Coelho I love seeing the recruiters or job sites that are actively and intentionally using deep personality insight to help connect employers with the right people.

Take someone like me vs. someone operationally oriented… both equivalent in marketing experience: what makes the right fit for BOTH the employer and the hire is culture, personality, and fit with the team – NOT experience and skills!

Dr. Manuel Blasini-Méndez reminds me of your work with entrepreneurs!

Alexa Schutz, MPA most definitely! Thanks for the tag!

Dr. Manuel Blasini-Méndez working on phase 2… perhaps we explore it together.

Paul O’Brien something to consider – less than 10% of women start-up founders get funded. That’s not because they lack these personality traits. How much of the personality data portrays a perception of what investors want to see and experience in founders? How many women founders were represented in the data set? How might this profile of success look different, if we looked at just women founders? How do we know what success might look like, if we funded as many women founders as men?

Jo Ann Hair Absolutely. Other studies demonstrate this in women and in my own coaching and organizing the success of women entrepreneurs is greatly influenced by preconditioning, childhood traumas and learned behaviors absorbed by women.

Jo Ann Hair Totally fair to flag the gap. Two things can be true: bias constrains who gets funded, and founder psychology still predicts outcomes. Kanze et al. showed VCs ask men “promotion” questions and women “prevention” questions, which likely relates (as it shifts capital)

My point in the article is to stop guessing.

Investors, startup programs, and cities should demand validated, outcome-linked trait data and publish subgroup results. Use instruments mapped to the Big Five, test measurement invariance by gender, and report fairness metrics like predictive parity. The UNSW work finds specific facets correlate with success and that personality-diverse teams outperform.

The thing is, they don’t. And it aggravates me that they don’t because this is the soundest science we have in startups. We’re here to help them do it, to help entrepreneurs know themselves and to better allocate resources – communities aren’t demanding it and so cities, investors, and startup development organizations disregard it.

Reduce bias by replacing vibe with science. We’re ready to help any investor, SDO, or city run it.

Paul O’Brien what is the definition of success used? It would be insightful to see what emerges from cohorts of women start-up founders. Would the same personality traits correlate with success? Might there be different ones? Are you suggesting that investors & incubators select ventures based on founder personality traits vs. leadership capabilities?

Jo Ann Hair across the various studies, I’m sure they have their own qualification of success; most, I find, tend to use the notion that they’re still operating after 5 years.

Would the same personality traits correlate with success? Might there be different ones?

Fair questions and at the same time, the point of my research in this case, and the spreadsheet analysis I have, is correlating the studies together – they generally reach the same conclusion. Hence my pushing that investors and cities should be demanding it, not ignoring it.

Are you suggesting that investors & incubators select ventures based on founder personality traits vs. leadership capabilities?

I’m not really in the business of suggesting… I look at data and direct what should be done. Oxford, a few years ago, found that these qualities result in a 8x greater likelihood of success ( https://seobrien.com/success-as-a-startup-founder-a-desire-for-variety-and-novelty-an-openness-to-adventure-reduced-modesty-and-heightened-energy-levels )

So, investors, cities, and startup organizations, can choose to ignore it but I was pretty harsh of them in saying that doing so is malpractice or neglect. The data speaks for itself.

that’s soo insightful

For founders, this means doing the hard work of self-awareness and surrounding yourself with the right people. For investors and ecosystems, it means moving beyond gut instinct and looking at the human factors that predict long-term success. At the end of the day, the most important thing isn’t just the idea; it’s understanding what your team needs to survive and grow and being intentional about building it.

It’s so true how much success hinges on the ‘who’ rather than just the ‘what’. Building a strong, intentional team around a solid idea makes all the difference, especially in the long run.

Stephanie A. Rieben-de Roquefeuil what founders should be building first and always foremost is a team capable and then the market relevant to the problem everyone is passionate about and fixated on changing. THEN the solution.

Unfortunately, most don’t want to hear this. To this day, I’m still fielding questions from founders asking how to launch their MVP when they have none of this developed.

90% of startups fail (so says conventional wisdom) and there is no reason the number is so high other than the fact that we aren’t discerning about whether or not the PEOPLE involved are capable and focused on the right things.

Team composition beats brilliant ideas most of the time. The founders who get this early save themselves years of painful pivots and rebuilds.

Sebastian Stockzelius in my experience, founders who get this early save themselves from the inevitable end that comes from a team that would see something implode rather than succeed without them.

Great insights, Paul. Too often we focus on product-market fit or metrics, when the reality is that founder mindset and team composition are what make or break a startup. I encourage entrepreneurs to take note: understanding your entrepreneurial DNA gives clarity on who you are, who you need beside you, and how to structure teams for resilience and growth. Investors and ecosystems benefit when this becomes standard practice rather than an afterthought.

Without question, not enough attention of finding Founder-Startup Fit

I’ve seen too many strong ideas implode just because the team wasn’t wired to carry the weight. Founders who build with that awareness early don’t just avoid failure, they actually scale faster because the team is already built for resilience.

Sebastian Stockzelius precisely. Mountains of research on this so we should be expecting that our Universities, Accelerators, and city programs, use it to help work out how to best help and entrepreneur. Teaching the fundamentals is worthless if the person lacks what it takes, while setting them up for unexpected failure.