From the freezing tundra of Austin, Texas, this weekend I was asked, “Is it true that the U.S. became a leading industrial power through entrepreneurship, innovation, and mass production, creating immense wealth?” and it struck me that this city being quiet on a Monday when the northern part of the United States is at work, is a perfect reflection of if, how, policy and entrepreneurship work in concert to create opportunity.

We’re going to talk about America here so for my readers elsewhere, put yourself in the shoes of policymakers in your part of the world, and consider the role local and national government plays in helping or hindering the work that you’re doing to make the world a better place.

America didn’t become an industrial superpower because a Senate subcommittee “managed innovation,” it happened because a ridiculous number of people with sleepless night habits kept figuring out how to make things cheaper, faster, and more reliable… and then scaled those improvements through mass production and national markets. The United States is a great petri dish in the creation or limitation of wealth through which, for most of its history, created unparalleled wealth throughout the world. The U.S. didn’t “discover” prosperity; it manufactured it.

And yes: entrepreneurship, innovation, and mass production are the core reasons the U.S. became a leading industrial power and then a leading global economic power.

The cleanest way to see it is to track what changed over time: not that Americans were uniquely virtuous, but that the U.S. built a system where (1) people could take risks and keep the upside, (2) ideas could be turned into repeatable processes, and (3) large markets could be reached cheaply enough that scale mattered. When those three show up together, “immense wealth” develops naturally.

Article Highlights

Entrepreneurship + innovation + mass production: the American flywheel

Long before “startup culture” became a buzzword even I use too much, Americans were doing the same basic thing: spotting unmet demand, applying a new method or technology, and then scaling distribution. The “American System of Manufactures,” interchangeable parts plus specialized machinery plus organized assembly, is one of the earliest forms of modern scale economics. Michael Goodfriend’s work with Carnegie Mellon, put together with University of South Carolina’s John McDermott, describes it as using interchangeable parts to reduce reliance on craft fitting, paired with the invention and diffusion of specialized machines.

That’s the bridge from “invent something” to “produce a lot of it without losing your mind (or your margins).” Interchangeability isn’t sexy, but it’s basically the reason you can buy an affordable anything.

When I look at the modern economy and see something like WordPress being used for most of the websites on the internet, or even ChatGPT interchanging all that’s available there, we see how humanity’s history with machines and scalability, applies even today.

Early versions of that system emerged in U.S. military armories and industrial manufacturing experiments, the benefits of which spilled out into public life as we uncovered the process of scale creating an increase of supply driving affordability: a breakthrough in process and standardization, followed by a flood of entrepreneurs who build businesses around it.

Then the U.S. did the very American thing: it scales that flywheel across a continent.

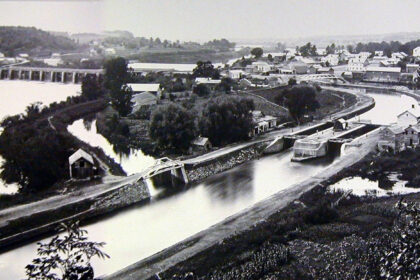

How? Think of transportation and logistics as silent partners and you’ll appreciate why the internet was coined the Information Superhighway. When moving goods costs too much, local artisans win. When moving goods gets cheap, scalable producers win. The Erie Canal is an early “oh wow” moment which slashed transport costs and time, effectively enlarging markets and enabling specialization and consumer trade. Railroads follow, then highways, ports, and air freight; the U.S. industrial story is also a logistics story uncovered in how Detroit and Chicago became the major cities that dominated the early 20th century economy.

Converting hand labor into seemingly limitless supply, mass production is where the wealth literally makes noise. Henry Ford is the cliché example because his impact was so evident: the assembly line and standardized parts turned automobiles from luxury items into mass consumer goods, which then created entire supply chains, cities, and labor markets around that scale.

And when the U.S. needed to prove it could out-produce enemies, World War II wasn’t so much the catalyst of American production, as it’s known, it was more like the venture capital investment in what already existed in nascent (“startup”) form. Faster than AI took all our jobs, U.S. aircraft production became the largest sector of the wartime economy (h/t Christopher Tassava), spilling out into public life in the form of the American airline industry and demise of the country being connected by rail (a sore spot for us still).

Hundreds of thousands of aircraft produced not because the Wright Brothers flew but demand, policy, and will, created the circumstances that organize capital, labor, and process at scale. That is how wealth is created: productivity – more output per unit of input.

Government doesn’t create wealth, but it can absolutely make it possible

A little aggravation of mine is hearing the trumpet from the White House celebrating how many jobs the President’s economic policy created. To be blunt and a little harsh, the two dumbest takes in American politics are (a) “government has no role” and (b) “government creates the wealth.’

Those assertions do a discredit to entrepreneurs while misleading people in ways that enable governments to get involved in the wrong ways, hindering value. Entrepreneurs convert uncertainty into products and services people pay for. Innovation creates new value by improving capabilities or reducing costs. Marketing and distribution decide whether the value becomes a business or stays a lab demo. Government doesn’t do that loop well because it can’t reliably price risk, it doesn’t face competitive discipline, and it rarely gets punished for wasting capital.

But government does matter, because markets require rules, enforcement, and shared infrastructure. Economists have been direct about this for decades, hoping the right role and responsibility sinks in. Douglass North’s work on institutions argues in Journal of Economic Perspectives, that institutions shape incentives and thereby the direction of economic change. North followed that research with what is called the “credible commitment,” a warning label: for investment and growth, the state has to credibly commit not to expropriate returns after the fact

“Institutions are the humanly devised constraints that structure political, economic, and social interaction. They consist of both informal constraints (sanctions, taboos, customs, traditions, and codes of conduct), and formal rules (constitutions, laws, property rights). Throughout history, institutions have been devised by human beings to create order and reduce uncertainty in exchange,” North in the simply named paper, ‘Institutions.’ “Institutions provide the incentive structure of an economy; as that structure evolves, it shapes the direction of economic change towards growth, stagnation, or decline.”

I’ve bolded stagnation and decline in quoting him because we’re all too easy to overlook the fact that the institution of government causes stagnation and decline just as much as it can foster the creation of wealth. Institutions have been devised by human beings to create order and reduce uncertainty in exchange, and they can just as easily enable restrictions, costs, or monopoly controls, that make things worse.

Still yes, government can help, when it does three things well.

1) Defending rights: property, contracts, speech, and the freedom to trade

If you want a society where people invest, invent, and build, you need them to believe the upside won’t be stolen by a monarch, a mob, or a bureaucrat with a pen and a crusade.

The Boston Tea Party era is often reduced to a children’s book about taxes, but it’s also about the legitimacy of extraction and monopoly privileges; every summary of the Tea Act consequences emphasizes the monopoly power and taxation legitimacy as triggers of revolution. The point isn’t “taxes bad;” the point is that arbitrary extraction and monopoly favoritism poison investment incentives.

We can (and should) look further back in American history. Most Pilgrims certainly weren’t libertarian saints; yet the early American experiment is saturated with fights over conscience, belief, and autonomy. Study of those who emigrated to the New World largely reflect religious nonconformity and persecution as key drivers of migration decisions (interesting, that the same thing could be said of a lot of migration today). The long arc of those foundational values eventually shows up legal commitments to speech and belief in the United States, two core issues which you might not fully appreciate the implication of in entrepreneurship… Speech is how markets coordinate whereas when you clamp down on expression, you don’t just hurt culture; you cripple discovery, persuasion, and trade.

Then, in the 20th century, “defending rights” grew to include those protections beyond U.S. borders with defense of trade routes and the ability to move goods globally. The Council on Foreign Relations’ Sea Power: The U.S. Navy and Foreign Policy is explicit about the U.S. Navy’s dominance being a guarantor of global trade. We can argue about the politics of it, but economically it’s straightforward: secure sea lanes reduce the risk premium on trade, lower risk premiums increase investment and commerce. Such protections are the foundation of global capitalism.

Here is where I hope, you can again see the implications to the Information Superhighway and how that forum of speech and medium of trade is subject to the exact same considerations, well beyond the interchangeability of WordPress. The U.S. became rich in part because it kept widening the “market for ideas,” not shrinking it. If we treat modern communication networks like controlled utilities where permission is required to speak, ship, or build, we’re not “saving democracy,” we’re kneecapping entrepreneurship while pretending it’s a moral victory. Rather, that’s not quite right, it isn’t pretending a moral victory, it’s propaganda that it needs to be controlled instead of protected, to “keep us safe.”

2) Investing tax dollars in infrastructure: the boring stuff that makes scale possible

Infrastructure is the underrated enabler of mass production. You can’t do national markets without roads, ports, rail, power, and communications. Entrepreneurs can build factories; they can’t sensibly build the interstate system.

The Erie Canal example is the principle: reduce transport friction and markets expand. The interstate highway system is the 20th-century version: restructure logistics, commuting, distribution, and regional specialization. The Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond published that the relationship of that with growth. Academic work keeps finding the same general direction: infrastructure investment can raise productivity and income growth under certain conditions, even as the details vary by place and design.

Electrification is another clear example which we should weave in here as we lead back to the internet and AI. Rural electrification changed productivity and enabled new economic activity in areas the private sector under-served because the payback period was too long or too uncertain. Without electrification, rural productivity lagged, widening the gap with urban standards of living; we can replace “electrification” with the modern era’s internet access or high-speed bandwidth.

The internet is not a folk tale where either “government built it” or “government did nothing.” The historically accurate version is that early networking and backbone efforts were government-funded (DARPA/ARPANET; NSFNET), for a time protected from infringement like our trade routes, enabling entrepreneurs and innovation to turn capability into the modern economy.

Government funds or coordinates certain kinds of infrastructure because the payoff is diffuse and long-term; entrepreneurs then build competitive products and markets on top of it.

Consistent with my point is history: the enabling layer matters but that’s not the same thing as creating wealth. Governments mistakenly try to fund startups when what we need from policymakers is focus on neutral infrastructure that founders can’t (and shouldn’t) allocate resources to fund.

3) Preventing corruption: not just crime but also market power, capture, and rigged access to knowledge

Corruption is broader than bribes handed out on park bench along the National Mall. We need to talk about monopoly power used to block entrants, regulatory capture used to cartelize a sector, and political self-dealing that turns public office into a trading desk.

A competitive market is an anti-corruption tool. When markets stay contestable, the next entrepreneur will challenge incumbents; when they don’t, you get rent extraction (wealth transfer dressed up as efficiency).

This is where antitrust shows up as pro-market, not anti-business. The Standard Oil case of 1911 is a defining example of government acting (however imperfectly) to stop monopoly behavior that restrained trade where The Supreme Court’s opinion framed the conduct as an “unreasonable and undue restraint of trade,” and the remedy dissolved the trust. Whether you like the “rule of reason” doctrine or not, the intent was to preserve competitive conditions rather than let private power become a parallel government.

One can argue we’re slipping a bit on this front because the same logic applies to internet platform monopolies and permissioned digital markets (Think, net neutrality or the causes of torrenting). If a handful of gatekeepers can decide who gets distribution, we don’t have a free market, we have an approval process. In many respects, Google, and increasingly AI, sort of decide what we know so appreciate the risks of controlling that, limiting it, or allowing politicians to be influenced by it.

The U.S. Constitution explicitly empowers Congress to secure exclusive rights for inventors “for limited Times” to promote progress while economists studying innovation history note that early U.S. patent institutions likely encouraged development by lowering the costs of adopting and copying foreign inventions (“IP maximalism” is not the same thing as “innovation” which requires mainstream adoption). Now, who makes the rules?

Thus, my anti-corruption / pro-competition posture on IP is not “abolish patents” and certainly isn’t “lock everything down,” it’s: keep IP rights limited, enforceable, and not easily weaponized by incumbents to block entrants. That includes cleaning up patent trolling, abusive injunction strategies, and regulatory games where compliance becomes a moat. When knowledge is in the market, which includes other countries making it available, it should become free use because to do otherwise enables foreign competition while handicapping domestic innovation.

If you really want to take preventing corruption seriously, we can’t ignore political self-dealing. Insider trading by public officials is a trust-destroying tax on the entire economy because it signals that rules are for civilians, not insiders. Even when it’s not prosecuted, the perception alone raises the “why bother?” factor for entrepreneurs who don’t have access.

Marketing is the wealth multiplier everyone pretends is beneath them

Most American industrial greatness wasn’t invention, it was commercialization. The U.S. repeatedly turned technical capability into scalable markets by pairing production with distribution, branding, and sales. You can invent interchangeable parts, but if you can’t sell the product at scale, you’ve created a neat museum exhibit, not wealth. A thought which again makes me reflect on University Tech Transfer offices (most of which are struggling with commercialization).

Marketing is not “ads.” Marketing is the discipline of understanding demand, positioning value, and building channels. It’s how innovation becomes adoption. That’s why American firms, across eras, created immense wealth even when other countries had comparable science: they were often better at commercialization (which is MARKETING, not licensing IP): turning new capability into solutions people would actually buy, and then building a system to keep selling it.

This is also why it’s a category error to claim government creates wealth. Government can create conditions, it can sometimes fund enabling infrastructure, but it does not do the iterative loop of customer discovery, pricing, persuasion, distribution, and competitive adaptation that turns novelty into market value, entrepreneurs do.

So yes, it’s true, and it’s also a warning label for 2026

The U.S. became a leading industrial power through entrepreneurship, innovation, and mass production.

Immense wealth followed because productivity rose and markets expanded. Government helped most when it defended rights, invested in infrastructure, and prevented corruption (especially monopoly and capture) without pretending it was the producer.

The modern risk is that we forget which parts are the canals and who makes the ships. If we throttle speech and digital exchange, treat AI as permissioned knowledge, let incumbents cartelize distribution, or allow political self-dealing to become normal, we don’t get “safety,” we get stagnation.

If you want a pointed way to test whether a policy is pro-wealth or just pro-control, ask yourself one thing: does it make it easier for a new entrant to compete or does it make permission mandatory or participation expensive?

Quite simply, it’s freezing in Austin, Texas right now, uncharacteristically, and we don’t have the same infrastructure in place to get everyone working. Economic policy takes entrepreneurship one way or the other.

Understanding how the government creates conditions rather than directly creating wealth is a powerful reminder for leaders, Paul!

Our energy and optimism are fueled by choices we make: about how we lead, connect, and empower others. When we focus on autonomy and inspiring action, we shine brightest.

What small shifts are you making today to energize your leadership and support your team’s growth?

Couldn’t agree more, the dynamic between policy and human ingenuity is like an iterative algoritm, always refining towards prosperity.

Well monopolies are in full swing and the power of the tech bros is to be mild, technocratic. We are not living in an era, at least right now, that offers incentives to entrepreneurs —not least for those who are “disloyal” to the thug in charge.

Rainboy, It *can* be. Feels like it increasingly hinders; I hope to help break that trend.

I’ve told city councils and developers all that city government’s job isn’t to create jobs, wealth or opportunity. It’s job is to create a fertile environment whereby the wheels of industry and commerce can flourish. This means good infrastructure and essential services, a reasonable and consistent regulatory environment, and a tax environment that pays for these things, but doesn’t try to gild the lilly in the process. Great article and I agree with your assessment.

Robert Hanna love this sentiment from Michael Bob Starr today, “‘build from scratch’ does not mean ‘do it yourself.’ Building a [startup] ecosystem isn’t about creating everything locally. It’s about leveraging what already works, building relationships, and establishing structure early so a community’s strengths can find expression. You borrow the bones from proven models and partnerships — then let the soul of the community give it life.”

That fertile ground enables collaboration. Enables. Then fosters. Too many local communities encourage it but have barriers to entry. That’s an easy way to look at good policy vs. bad: enable everyone first and foremost.

Paul O’Brien yeah, that Michael Bob Starr is on to something in the Key City.

Working to semi- build my own Mission Statement into the possibility of a new startup…only to get it going…mot to be The Driver!!

John Moore

Why

Who

When

Where

What

How

Little trick I learned to get messaging a startup right

interestingly, that same observation can be applied to China over the last two decades…

I thought about writing this with global evidence but the question asked about the U.S. so I went with that for now… maybe I’ll dig deeper with more examples.

it’s fascinating for sure

Agree 100%. Gov can foster the framework so entrepreneurship thrive. Entrepreneurs do the rest, amazingly.

No, the US got rich due to becoming the world’s reserve currency because most of the rest of the world’s manufacturing capacity was either demolished or still developing post WWII

Joseph Petersen anyone who just comes at with me “no” gets an expectation of an explanation. I write to explain and encourage critical thinking, not to assert that I’m right.

The U.S. was *already* the world’s largest economy and industrial power before being the reserve currency; wealth was driven by productivity growth, industrialization, entrepreneurship, and mass-market innovation, not monetary status. This is my sharing the Erie canal example, the protections established by the Pilgrims and the Tea Act, and Ford… which I then pointed out means WWII was more accurately the investment in that, rather than the creation – airplane manufacturing wasn’t created by WWII nor did it replace everywhere else because of WWII, we were already doing it, WWII accelerated it.

What you’re suggesting is like saying the U.S. has most of the wealth in social media because other countries restrict it; U.S. was already doing it all – it’s the entrepreneurs that *created* it. If anything, this reinforces that other countries are missing out on the same because of their policies.

Reserve-currency status is largely a byproduct of economic strength and comes with real costs like trade deficits and deindustrialization, rather than wealth creation.

Curious on how to make this work for a country like Nigeria

Thanks for this! I am too; I’m going to dig into some research and will probably write up some thoughts about Nigeria next week.