Don McLean’s American Pie is usually shared as an elegy for rock ’n’ roll and American innocence. It’s a song with tremendous meaning to me, sung as a group while my high school class graduated, I went to study the lyrics and history in college, teaching myself how to build and website (then with notepad, html, and ftp) so I could publish my assessment of the lyrics where others might enjoy. In the 30 years since that analysis of American Pie (here if you’re curious) was published, I’ve heard from thousands of fans, academics, and even a few documentaries, citing what became my first webpage on the internet.

It just so happens that today, February 3rd, is not only 30 years since I published, it has been 67 years since The Day the Music Died; on February 3, 1959, American rock and roll musicians Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and “The Big Bopper” J. P. Richardson were all killed in a plane crash near Clear Lake, Iowa, coined when singer-songwriter McLean referred to it as such in his song.

Article Highlights

Today the Music Died

Music defines my life in many ways, but my work online has evolved from curiosities about lyrics and music history, to instead shape startup ecosystems, guide founders, and serve venture capital. With that in mind, if you’ll roll with me, I thought explore the lyrics from a different point of view and consider if we can shape them from what they actually mean, to instead be meaningful to founders.

Listen instead to a long, bruising post-mortem of a startup, and it works. The song becomes a founder’s retrospective on the day the startup died, told years later by someone who’s lived long enough to understand why it was inevitable. Something from which we can learn.

The genius of the song is that McLean never narrates the “death” directly. He circles it, mythologizes it, disguises it in symbols and scenes. That’s exactly how founders talk about failure too. Nobody says, “we misunderstood distribution and burned runway.” They say, “Things just changed,” or “The market moved,” or “It stopped feeling like fun.” The day the music died is the day belief collapsed; when momentum, morale, and meaning broke before the cap table.

McLean opens with childhood, learning to sing, faith in music, belief that something pure could last forever; he’s describing the pre-startup phase – naïve optimism in the first idea that feels obvious and righteous. The early conviction that if you just work hard and stay true, the world will reward you. Every founder starts there. You don’t quit a safe job because you ran the numbers; you quit because you felt something.

News arrives and “February made him shiver,” the first real signal shock. For us in this different context, perhaps a competitor launches, a platform changes its rules, or a key partner or cofounder pulls out. It’s not fatal but it is cold. You realize the game is bigger than your product. Founders still think grit alone will save them.

As the song moves into scenes of celebration: the levee, dancing, and singing; you’re in the early traction phase with demo days, some social media traction, and early users telling you they love it. Advisors are nodding enthusiastically while everyone is drinking the same optimism (repeating the same refrains). But the levee is dry and that’s a tell too many of you ignore: there’s no underlying flow – no real distribution engine and no repeatable growth. Just vibes.

“The jester” and the shifting cast of characters mark what you might think of as a professionalization phase: consultants, investors, accelerators, service providers swoop in to help given the hype. Often, the founder stops being the storyteller and starts reacting to other people’s narratives. Strategy decks replace execution and the vision gets abstracted into playbooks as the team grows with managers who need to know how to manage people. The company sounds more impressive but feels less alive.

By the time the song reaches the chaos of missed signals, crossed wires, and battles between factions, it’s late-stage dysfunction. This is when startups confuse motion with progress: meetings multiply, metrics contradict each other because no one really even knows what KPI means, and culture fractures. Everyone senses the music is off, but nobody wants to stop the show.

And then the refrain lands again as it does throughout, “the day the music died” but this time, here, it means something. Not bankruptcy nor shutdown, that comes later, this is the day the founders stop believing the story they’re telling. This is the day hiring gets harder because the spark is gone. The startup is still operating but it’s already dead. What makes Don McLean brutal here is his refusal to assign clean villains. Just like in startups, nobody killed the company alone as incentives drifted, signals were misread, and power consolidated in the wrong hands. Creativity was crowded out by safety. Leadership lost among advisors, consultants, agencies, and investor priorities. Execution died to risk aversion. All that made it special was slowly optimized away.

The final verses (quiet, reflective, unresolved) are what founders sound like years later after the “failure was the best thing that happened to me” speeches.

There’s wisdom, sure; but also grief. Because something real did die, and pretending otherwise is cope.

Let’s see what we can learn: American Pie Lyrics

A long, long time ago…

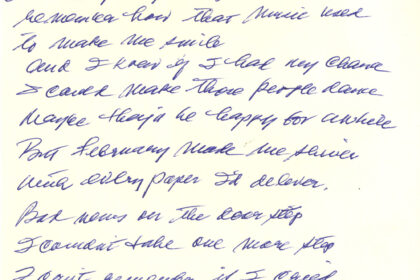

I can still remember how That music used to make me smile. And I knew if I had my chance, That I could make those people dance, and maybe they’d be happy for a while

“American Pie” becomes the founder looking back at the early years of “startup America” when the playbook was simpler, the community was smaller, and the feedback loop between creator and customer was perhaps more honest. In startup terms, this is the era before growth hacks, before “blitzscaling” became a religion, and before everyone learned to talk like a pitch deck.

This is founder origin story. The “music” is the first version of the product that works, not in a theoretical TAM way, but in the “holy hell, people actually like this” way. Making people dance is product delight while the “happy for a while” is the honesty every founder eventually learns: early traction isn’t permanence; it’s a temporary window where novelty + novelty distribution + novelty demand align. The smile is the dopamine of being understood by strangers.

But February made me shiver,

Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and “The Big Bopper” J. P. Richardson, died on February 3, 1959 but in our variation, this is the moment the market turns cold in that platform change or a competitor finding funding. Perhaps it’s a regulatory shift, increasingly common and part of the work I do to prevent such things happening. Maybe a key channel dries up. Typically, this isn’t really a lesson learned because we teach founders to pivot; no, this is physical as founders shiver and feel it in their gut.

With every paper I’d deliver,

This is the unglamorous part most of you only appreciate later despite it being one I rant about alongside many; the hustle phase where you’re doing work that doesn’t scale, such as selling manually, handling support yourself, and shipping at midnight. Worse, while some, along with me, are pushing you all to do marketing instead, bad advice is telling you to do things that don’t scale (largely only because people don’t know how to do marketing, so they tell you instead to sell). “Every paper” is every cold email, every demo, and every awkward first sale merely keeping the lights on while you pretend you’re getting validation.

Bad news on the doorstep… I couldn’t take one more step. I can’t remember if I cried When I read about his widowed bride

Bad news hits founders like grief because it is grief: you’re mourning the future you had already started living in your head. The “widowed bride” is a harsh startup metaphor: the company wasn’t just a project; it was a relationship. Something you committed to publicly. Something you planned your life around. When the bad news arrives, your identity gets widowed before your cap table does.

But something touched me deep inside, the day the music died.

Here’s the core translation: the startup dies when the founder feels, unmistakably, that the thing no longer has a pulse. In venture land, people try to turn this into spreadsheets with CAC/LTV, runway, and burn rates. Sure, those matter, but we also write about Grit, Passion, and Tenacity, because every “dead company walking” has a moment where the founder knows, privately: distribution isn’t working, retention is lying, the team is pretending, the story feels fake coming out of their own mouth. It isn’t working.

So…

(Refrain) Bye bye Miss American Pie,

“Miss American Pie” is the beautiful, naive version of the company; the one you pitched when you still believed the market would reward effort and charm. It’s also the myth of inevitability (we’re building the future, therefore we must win). Bye bye is goodbye to innocence.

I drove my Chevy to the levee but the levee was dry, Them good ol’ boys were drinkin’ whiskey and rye Singing “This’ll be the day that I die, This’ll be the day that I die.”

This is founders joking about failure long before they believe it. Every startup has this gallows humor phase: “If this doesn’t work, I’m going back to consulting.” The irony is that when founders joke about dying, it’s usually because something already feels off: the levee is dry. The channel they assumed would carry them isn’t carrying anything. So, they drink (metaphorically or literally) and keep repeating the story because silence would force acknowledgement.

Weaving together narratives for a moment, I want to touch on the interesting correlation with the fact that we tend to appreciate that the ideal startup founding team is 3, not two and certainly not a sole founder. In Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and The Big Bopper, we have our CEO, CMO, and CTO, the 3 ideal to the founding team, singing, “This’ll be the day that I die.”

(Verse 2) Did you write the book of love, and do you have faith in God above, If the Bible tells you so?

This entire verse is about belief systems and what founders trust when things stop being simple.

When a startup is young, belief is emotional: people love it, it feels right, this should work. As pressure increases, founders start reaching for substitutes for real market truth.

“Did you write the book of love”

This is the founder asking whether the original story was ever real. Did we actually understand customers, or did we just romanticize them? Was the insight authentic, or a projection?“Do you have faith in God above, if the Bible tells you so?”

This is authority-based belief. In startup language: investors, accelerators, famous founders, playbooks, dogma. Is it true because someone important said it?

Now do you believe in rock ‘n roll? Can music save your mortal soul? And can you teach me how to dance real slow?

Rock ’n’ roll here is the thing itself: the product, the craft, and the act of building. The question is tough – Do you still believe in what you’re making, or only in the narrative around it? Founders often hope the product will redeem everything: the sacrifice, the debt, the stress, and the relationships strained. This line asks whether the company can actually justify the cost of founding it.

“Can you teach me how to dance real slow?”

This is about execution discipline. Not hype. Not speed. Can you operate with patience, restraint, and rhythm, or do you only know how to sprint?

Well, I know that you’re in love with him ‘Cause I saw you dancing in the gym

This is the founder watching customers fall in love with something else. The “gym” is the open market where other students are watching. This is where denial starts to crack.

You both kicked off your shoes

Early adopters committing. They’re not just flirting, they’ve invested time, data, and habit. Switching costs are forming, just not in your favor.

Man, I dig those rhythm ‘n’ blues

This line is about roots. In startup terms, it’s the realization that what works is often older, simpler, less flashy than your innovation. The market rewards fundamentals, not novelty.

Before the popularity of rock and roll, music, like much elsewhere in the U. S., was highly segregated. The popular music of black performers for largely black audiences was called, first “race music,” later softened to rhythm and blues. In the early 50s, as they were exposed to it through radio personalities such as Allan Freed, white teenagers began listening too. Starting around 1954, a number of songs from the rhythm and blues charts began appearing on the overall popular charts as well, but usually in cover versions by established white artists, (e.g.”Shake Rattle and Roll,” Joe Turner, covered by Bill Haley; “Sh-Boom, “the Chords, covered by the Crew-Cuts; “Sincerely,” the Moonglows, covered by the McGuire Sisters; Tweedle Dee, LaVerne Baker, covered by Georgia Gibbs).

I was a lonely teenage broncin’ buck with a pink carnation and a pickup truck

This is the founder archetype: confident, undercapitalized, overcommitted, powered by identity and charm. The pickup truck is independence, and the carnation is performative confidence. You look like you belong (even if you’re improvising everything).

But I knew that I was out of luck The day the music died I started singing…

Here’s the first explicit founder self-awareness moment. Luck didn’t really run out though, fit did. The realization that no amount of hustle fixes a solution that no longer resonates.

Refrain

(Verse 3) Now for ten years we’ve been on our own and moss grows fat on a rolling stone

This is what happens after the golden age of the startup; the ecosystem professionalizes, money pools, and bureaucracy creeps in. Founders stop moving, stop experimenting, stop risking. The “rolling stone” settling is what happens when success calcifies into comfort.

Bob Dylan wrote “Like a Rolling Stone” in 1965, his first major hit. How about these lyrics relevant in a startup failing, “You used to laugh about, everybody that was hangin’ out, now you don’t talk so loud, now you don’t seem so proud, about having to be scrounging your next meal“?

McLean could have also been The Rolling Stones as many musicians were angry at the Stones for selling out when they became citizens of another country merely to save taxes. In our case, maybe disappointment in selling out to investors, an early exit, or a bad deal out of desperation?

But that’s not how it used to be when the jester sang for the King and Queen

In the song, the jester is Bob Dylan, as will become clear later. The king some think is Elvis Presley, which would be rather obvious, while the queen of the time might have been Connie Francis or Little Richard. What we lack here is why the jester sang to them. Instead, historically and interestingly, it works as the Kennedys (the King and Queen of “Camelot”), who were present at a Washington DC civil rights rally featuring Martin Luther King where there is a recording of Dylan (the jester) performing… which hints that the jester could instead be Lee Harvey Oswald who sang (shouted) before he was shot for the murder of the King (JFK).

Apologies though that I went off track (or rather, on track) in my passion for the song and history. In our case here, let’s say the jester is the founder: irreverent, honest, and dangerous, while the king and queen are capital and culture. Early on, founders challenge that power while singing to it for support. Later, failing, founders perform for it.

In a coat he borrowed from James Dean

In the movie “Rebel Without a Cause,” James Dean has a red windbreaker .that holds symbolic meaning throughout the film In one particularly intense scene, Dean lends his coat to a guy who is shot and killed; Dean’s father arrives, sees the coat on the dead man, thinks it’s Dean, and loses it. On the cover of “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan,” Dylan is wearing just such a red windbreaker, posed in a street scene similar to movie starring James Dean.

For our purposes, our founders (the jester) lend the coat of experience to team members who have moved on and who themselves try to start something. Given similarities drawn from experience, as those startups die, friends and family too anguish.

In a voice that came from you and me

Startups speak from lived pain and direct experience but a voice that matters also listens to and uses the voice the market: you and me. While dying, the founder sings with a voice that has more appeal now drawn from their audience.

Oh, and while the King was looking down the jester stole his thorny crown

This is the moment when a founder stops being an outsider and becomes the establishment they once mocked.

The king is the incumbent logic: old capital, old industries, old rules. Our jester, the founder, irreverent, underestimated, and allowed to speak uncomfortable truths precisely because they have no power, now has what appears to be success – they “steal the crown.”

In startups, this is the moment when the founder wins legitimacy: big funding round, press validation, or marquee customers; they are no longer protected by scrappiness, they are now accountable to the system they probably once criticized.

The crown is thorny because scale introduces incentives that punish honesty. The founder can no longer say what they really think and the product doesn’t really do what they really wanted to do; governance replaces instinct and optimization replaces creation.

This is not victory; it’s transformation and often the beginning of the end.

The courtroom was adjourned; no verdict was returned.

This is the most damning lyric in the entire song for entrepreneurship because in startup terms it’s failure without truth. No verdict means no clear reason given, no post-mortem. no accountability, and the assertions that the company didn’t “fail,” it “pivoted,” “merged,” “soft-landed,” or “returned capital.”

The courtroom exists (boards, investors, customers, the local community, and media) but it never really renders judgment so much as the rumor mill floats opinions. Founders never learn, other founders never really learn, investors never admit the mistakes, and patterns repeat.

(This is how bad ideas get recycled with new logos and new pitch decks)

And while Lennon read a book on Marx,

This is the moment when the company’s internal conversation shifts from customers and craft to ideology and power. “Marx” here is shorthand for systems thinking about control (who owns what, who decides, who gets paid, who is exploited, who is allowed to win). This is when the team starts sounding like they’re doing sociology instead of shipping. Sometimes that’s necessary (labor, fairness, governance) but most of the time it’s a tell that the company has drifted from direct value creation into narrative warfare.

Notably, we’ve added Lennon to our cast of characters so at the risk of this getting too confusing, let me continue to steer you to the notion that we’re still talking about the founding team, but instead of using the ideal of three, we’re talking about The Beatles, with Lennon the 4th addition to our three…

The quartet practiced in the park

See it? What quartet speaks volumes in music but The Beatles?? Here, the founding team is rehearsing the act of being a company. “Practiced” is the key word as they’re getting good at demos, pitches, brand voice, and culture rituals, particularly at this stage trying to evolve into a company (and often before actually being any good at consistently producing value). And what do we have here? Lennon, one of our founders, starting to deviate from the rest.

“In the park” is public space: incubators, meetups, demo days, social media. You’re building in front of spectators.

And we sang dirges in the dark

A dirge is mourning music. Why are we singing dirges in the dark? The product stops being joyful and becomes a coping mechanism. The work turns into elegy: long internal threads, solemn all-hands, “we’ll get through this” speeches, post-mortems that aren’t honest. “In the dark” is the lack of clarity as well as hiding the struggle from customers. Your dashboards don’t explain what’s happening, you aren’t being honest about the difficulties, Lennon is off considering a different model, and your customers aren’t telling you the truth.

The day the music died. We were singing…

Refrain again “Bye bye…”

Let’s revisit it this time because now is the explicit marker: the day the startup loses its living relationship with the market. We’re not shutdown yet, we’re not insolvent. This is the day feedback loops break, the vision is gone, the alignment stops, and execution has been replaced with managers.

“Chevy to the levee” is now taking your reliable old tools (your hustle, your network, and your competence) back to the place you expect the flow to be only to find it is indeed dry. Our “Good ol’ boys…” are here the inner circle (founders, early believers, early investors) self-medicating with certainty, often doubling down instead of seriously changing, haunting us again with “This’ll be the day…” as a gallows prophecy: the company repeating its own funeral line to avoid admitting reality out loud.

(Verse 4) Helter Skelter in a summer swelter

Chaos. The company loses a single strategy and starts chasing five. Worse, overheated market conditions: too much money, too much hype, too many competitors, and too much noise. Everyone’s sweating; nobody’s thinking.

The birds flew off with the fallout shelter

Your key channel or partner leaves and the protective story goes with them. The “fallout shelter” is whatever you were hiding inside: brand halo, platform dependency, a distribution deal, or an investor’s reputation. When it goes, you’re exposed to reality.

Eight miles high and falling fast

This is the company floating above the market: talking future, talking platform, talking grand vision, talking TAM (which is a truly irrelevant metric unfortunately hyped in pitch deck workshops), while users are trying to solve basic problems. Gravity is retention, churn, CAC, activation, and referral; it always wins. Falling? It’s going to hit hard and hurt.

It landed foul on the grass

Your pivot misses the field. Perhaps a new launch you hoped would save things. This is, “we built the wrong thing for the wrong buyer,” why and how? Because you took that “do things that don’t scale advice” and talked to a handful of customers while dropping cold emails while ignoring marketing – The grass is where customers live, on the field; if you don’t design for the field, you don’t have a business.

The players tried for a forward pass

The team tries to force progress: new features, new positioning, new pricing, and new sales hires (after all, sales and customers solve every problem, don’t they??) You try anything that looks like moving forward.

With the jester on the sidelines in a cast

Wow. If you’re a failed founder, you felt this line. The founder at this point in a startup is increasingly sidelined: burned out, pushed aside, constrained by board pressure, or psychologically checked out. The founder can’t “play” anymore; they can still talk, still pitch, and still attend meetings, but they can’t create the music.

Now the half-time air was sweet perfume

Okay, take a breath here because that last Board meeting made you feel good that we’re going to get this back on track. It’s half-time and we’re getting back in the game. And why not? This is the intoxicating distraction layer: awards, conferences, press, and social buzz. Perfume covers the smell of decay.

While sergeants played a marching tune

The institutionalization that crept in, the professionalization of process, reporting, and compliance, in the form of OKRs, forecasts, and board decks, the company becomes a marching band. Playing a rigid tempo with no improvisation, you know where this is going…

We all got up to dance oh, but we never got the chance

The team is ready to do the fun part: ship, win, delight customers, and feel alive again! The machine won’t let them; the company is too heavy, every move requires permission, coordination, and risk management. The music can’t breathe and the jester is in cast.

‘Cause the players tried to take the field, the marching band refused to yield.

The creators and marketers try to get us back on the field but the system refuses to stop controlling. This is the heart of later-stage startup death: control beats creativity.

Do you recall what was revealed, the day the music died?

This is the moment of revelation founders remember forever: the day you realize you never had product-market fit, or you lost it, or your channel is gone, or your economics are terminal.

We started singing

Refrain

(Verse 5) And there we were all in one place

If you know the song well, you know this is where the melody changes tempo and gets upbeat. We’re in the startup hub downtown, going to the same conferences, supporting one another with encouragement that feels good while it masks groupthink. You maybe add a go at an accelerator, all of which are merely preaching Lean Startup, so there you go; everyone is solving the same problems with the same tools, but at least we feel optimistic again.

A generation lost in space

I seriously laughed this one being so fitting. What the hell are you all doing trying to plugged into the local “community” through some physical space for startups!? These are founders detached from real buyers and startups with no meaningful tie to their sector or potential partners, because you’re sitting there in a startup space wasting your time thinking that the celebrated space will save you.

With no time left to start again

Runway is gone, but more importantly: psychological runway. The founder can’t restart because they’re depleted or trapped by identity and sunk cost.

So come on Jack be nimble Jack be quick

The culture screams speed: Move fast! Iterate, ship… “Nimble” becomes morality.

Can you believe how fitting this is for a song that was written in 1971??

Jack Flash sat on a candlestick

Jack of course, being a nickname of the founders, “Come on dude,” with Flash added because you’re quick now – instead of correct. Velocity becomes the substitute for insight.

Candlesticks are market charts: spikes, hype cycles, short-lived momentum. “Sat on” implies riding the spike: building a company on a temporary candle instead of a durable base.

‘Cause fire is the devil’s only friend

Why? Because fire is burn and burn is thrilling until it isn’t. Burn attracts attention, but it also consumes the only thing you truly have: time.

And as I watched him on the stage, my hands were clenched in fists of rage; No angel born in hell, could break that Satan’s spell

The founder watching the company turn into theater: keynotes, brand performance, story performance: less substance. This is the founders are angry now realizing they helped create a machine that rewards only rewards performative behavior over truth.

“No angel” come on, you have to have be loving this as much as I do! Angel Investors, even those born of the startup environment itself, can get people off the gravy train of revenue (the fire of Satan’s spell) meaningful now, here in the staging of the startup, because it’s wrong.

And as the flames climbed high into the night, to light the sacrificial rite

Burn intensifies. Stakes rise. Pressure rises. The company is spectacularly on fire. Particularly at night, in the dark with no real visibility; you’re burning now, blindly. What do you do? What did you do? Layoffs.

Someone gets sacrificed: employees, early customers, founder health, relationships, ethics, product quality. Startups often pretend this is “necessary.”

I saw Satan laughing with delight

The market doesn’t care; hype doesn’t care. The ecosystem doesn’t care. If you can’t make people dance, the world moves on.

The day the music died He was singing…

Refrain

(Verse 6) I met a girl who sang the blues

Tune in the music again, our tone shifts in the melody here, it slows… it’s almost melancholy. You meet the customer’s real emotional state: skepticism, fatigue, and distrust. They’ve been burned by tools like yours before. You talk to some of your customers and they’re genuinely sad.

And I asked her for some happy news, but she just smiled and turned away

Founders fishing for good signals: “Any excitement?” “Any chance you’d share this?” “Can we count you for referrals?”

The coldest market response isn’t hate, it’s indifference.

I went down to the sacred store where I’d heard the music years before

You return to where the magic used to happen: your old channel, your old community, or your old distribution source. Nostalgia sinks in as you remember when shipping felt like flying and users felt like friends.

But the man there said the music wouldn’t play

That channel is gone. That era is gone. That advantage is gone. Past traction doesn’t replay on demand.

And in the streets the children screamed

The broader world is in chaos: layoffs, political turmoil, platform shifts, economic cycles. Your company is not insulated and what we’re reminded of here are the start of the lessons – the tense changes to PAST tense. The music wouldn’t play again, but in the streets remember, the children screamed. YOU ignored that.

The lovers cried and the poets dreamed

Your customers AND the market (not just customers!!) tried to tell you but you didn’t listen to the crying. People who loved the mission kept trying to keep you on it. Storytellers, influencers, and journalists, dreamed of the future you promised but you didn’t stick to it. Besides, dreams don’t fix distribution; it is understandable that you were torn.

But not a word was spoken, the church bells all were broken

But, back to the PRESENT, silence from the market, silence from the press, silence from users, the scariest signal. Want a religious parallel if only because it’s evident here? Those three founders: CEO, CMO, and CTO… Holly, Valens, and The Big Bopper…. are in the Christian religion very relevant in 1970s America, are the Holy Trinity… the Church bells have stopped ringing for them.

And the three men I admire most The Father, Son, and Holy Ghost

This could obviously be those 3 founders, leaving and moving on (as the next line brings about). But we could also see here pillars of your identity as a founder: your mentors, your heroes, your original inspirations, or, in a company sense, the three core legs: solution, market, and resources.

In a mythic trinity, this could be soft of a holy trinity founders worship without admitting it: truth, trust, and traction.

The lesson here? Lose one and the other two collapse. CEO, CMO, and CTO. Solution, Marketing, and Resources. Truth, Trust, and Traction. Too many founders don’t even lose one, they ignore it. That is why you fail.

They caught the last train for the coast

This is actually not leaving in failure because again, the coincidences are uncanny with the coast being the California coast – Silicon Valley? A last chance to pivot, to recover, or to re-found. The last train is your final window of optionality. Typically in a demise of a startup? An acquihire. Maybe a move to somewhere else.

The thing is that the coast is where things “end” in American mythology.

The day the music died

And they were singing…

Refrain (2x)

Even at the end, the system keeps singing the old chorus. Founders keep pitching. Investors keep tweeting. Ecosystems keep hosting events. But this song is over.

By the last chorus, the refrain isn’t denial anymore. It’s memorial. It’s the founder admitting: we kept repeating the old lines because we couldn’t face the moment the music stopped.

What American Pie Really Teaches Founders

Read this way, American Pie stops being a nostalgic riddle about music history and becomes an eerily precise anatomy of how startups too frequently die.

The song never treats death as a single event and in a startup it isn’t. There is no moment where everything collapses at once. American Pie documents drift: belief replaced by ritual, craft replaced by performance, feedback replaced by ideology, and rhythm replaced by control. The “day the music died” is not the day the company shuts down or exits; it is the day it loses its living conversation with the market. Everything after that is administration.

What made McLean’s lyrics mean so much to me is that they capture culture, history, and psychology in a narrative of downfall better than any post-mortem email to stakeholders. The early verses are full of innocence, joy, and communal creation: the founder phase, when people dance because the product speaks to something real. As the song progresses, success hardens into hierarchy, experimentation gives way to marching orders, and institutions form that cannot yield even when the builders are ready to play again. By the time capital, process, and reputation dominate, the music has already stopped.

But what it reveals is that you didn’t actually listen. You went in on the groupthink space. You disregarded the third part of the trinity. You took the thorny crown of celebrity and turned away from your mission.

The lesson is not sentimental, and it is not kind: startups do not die from lack of effort, talent, or capital. They die when they stop making people dance; when they stop listening to the rhythm that makes people dance and instead replace it with structure, certainty, and story – which no one wants.

If there is one thing I hope you enjoyed and learn to hold on to with me, it’s listen to the music: retain your music. The moment you can no longer hear it, the end has already happened, we merely have another refrain to play before it’s over.