Data. Statistics, measurements, and analytics are funny things, particularly in entrepreneurship, as if you think about it, data is invaluable but difficult to aggregate, informational but difficult to consume, technical but immensely educational. Why so hard when so important? Data geeks such as myself often find ourselves lost in the weeds; we love mining information so much so that the idea of analysis paralysis is likely born of our own penchant for wanting data more than others’, less data oriented, experiencing information overload. As a startup evangelist, I often find myself pushing for “market validation” more than “customer validation” but that begs the challenging question of how entrepreneurs find validation at scale.

Consider a fundamental question you should be asking yourself as the founder of a venture: is validation from customers sufficient evidence for what you aspire to do or might you instead/also in need of mass market validation by way of large data sets and research? There is no right nor wrong answer (unless you’re of a school of thought that thinks there is). Personally favoring market validation, I’m the type who looks to failing startups that had customer validation as confirmation that I’m right; confirmation bias that, had they only invested in market data, they might have known to avoid the mistakes they made. My bias doesn’t make me right though, it only affirms that neither customer nor market validation is alone sufficient. Data. How might we deliver both customer and market data to the world to help everyone avoid either deficiency?

The challenge is that collecting, mining, and understanding data, so as to validate a new venture or merely to make a decision in business, is incredibly difficult.

Once the domain expertise of Marketing, Finance, and Information Analysts, our collective experience with data has shifted from focus groups and surveys to technology and data mines; from the world of marketing to that of information technology. Few have had experience in both worlds and thus few have understood not just how to aggregate and access tech enabled information, but how to use it and why.

This election cycle, as an example of the challenge of presenting data in a meaningful way, the Associated Press debuted “Election Buzz,” a tool that uses Twitter and Google data to track the U.S. elections and many of us data geeks rejoiced!

Finally, a tool that leverages social data to give us real insight to U.S. Politics!! An end to the biased era of exit polls and media surveys and the dawn of the true information age. No more customer validation, let’s start looking to what the data says!

The marketer in me rejoiced. Always excited when consumable datasets emerge that help validate the flaw inherent in risking everything on a new venture with customer validation alone.

What the heck does an exit poll know of who is going to win the election!?

In the news March 9th: “Bernie Sanders pulled off a shocking upset in Michigan’s Democratic primary Tuesday night, beating Hillary Clinton in a race that most polls had him trailing by double digits and eclipsing the front runner’s earlier win in Mississippi.”

But, frankly, my honeymoon with Election Buzz was over almost as quickly as it had begun. This is the same thing we had built at Yahoo 15 years ago… it was similar to what Dachis Group was doing a handful of years ago. Damn. Tech and information applied simply for the sake of headlines rather than real information innovation. More proof that collecting, mining, and really understanding what data has to say is exceptionally difficult.

Having now spent more than a few years in Austin, and witnessing here the convergence of, for example, Silicon Valley’s tech with New York’s finance and media experiences, by way of the significant immigration to Texas, it has become clear that Austin is where such worlds are colliding. That convergence is bringing technology to the real world and with it the data that’s causing enterprising entrepreneurs to solve the problem of inaccessible data.

“Tech itself will only ever lead the economy temporarily and in cycles.” cites Brian Hoffman, San Antonio based Intelligence industry Product Manager, “It has always been a means to another end. We happened to be alive during a period of significant tech advances, which always begets innovations to use those advances. A flurry of new skills and jobs are needed to meet the demand for those innovations, because of course we must learn how to wield them first. You never really know where the peak of that demand is going to be, so you ride her til she bucks you.

As long as Maslow’s hierarchy of needs remain unmet universally, the driving force behind markets will always be goods and services.”

Article Highlights

Making Data Meet Our Hierarchy of Needs

Fifteen years ago, Yahoo was doing something very similar to Election Buzz. Imagine that. Much like so many startups that fail to achieve market dominance, we have a product that’s failing to actually meet a significant market opportunity. Why don’t the previous data presentations of election information still exist? Because our need isn’t being met by a pretty chart summarizing results. Without the convergence of real data science and market analysis, with concepts such as natural language processing, predictive analytics, and more, we’re delivering the same experiences as over a decade ago AND/OR failing to recognize the failures of what came before; inventing them again and relaunching experiences that are little more than a new skin. Thanks, ironically perhaps, to a lack of data about what really matters to the market.

Failure, of course, is a key tenet of entrepreneurship. But such failures: failing to succeed in a new venture simply because of a lack of data about what’s been done before?? That’s the inexcusable mistake we must strive to overcome. Begging the more important question: how does one avoid making mistakes so as to bring to more successfully bring something to market?

Data.

Since the nineties, Big Data has been available but it has been locked in the minds and technologies of engineers and data scientists. I recall looking on with amazement at the amount of information Yahoo collected about individuals simply by way of users’ engagement with the once dominant internet property. ‘What could be done with it??’ we wondered.

It was immediately obvious how companies that amass massive audiences are worth billions despite their not selling anything?—?never before had it even been possible to know so much about individuals, communities, regions, markets, industries, or economies. The internet in one fail swoop dawned the information age and in many respects made ignorance inexcusable, but failed to make it consumable.

It was immediately obvious how companies that amass massive audiences are worth billions despite their not selling anything?—?never before had it even been possible to know so much about individuals, communities, regions, markets, industries, or economies. The internet in one fail swoop dawned the information age and in many respects made ignorance inexcusable, but failed to make it consumable.

One million men from Silicon Valley (meaning 140,000 work in tech, 450,000 have a college degree, and all live in one of most expensive places in the world) in one 2,000 square foot bar?! Snarky comments aside, that’s a veritable gold mine of success, as long as one has the means to do something with that market.

And there’s the rub, this was at a time before the technology existed to make data manageable, we had databases but few user friendly data tools. More importantly, it was as a time before traditional industries had the opportunity to form any concepts on the implications.

For the better part of the last fifteen years, those worlds have converged: technology and market. The technology has developed, evident in, Google’s application of algorithms and scalable databases, APIs that essentially open source information so that other developers can invent upon data sets, Twitter and LinkedIn radically maturing our understanding of the social graph, and companies like Sprinklr (and Austin’s Dachis Group before that) making such data available to everyone in a business. In parallel, the market has matured as the internet and technology have grown from niche industries to ubiquitous considerations of every business. Internet technology has evolved through changes perhaps easily understood by the decades that constrained the set of milestones that have passed. The nineteen eighties brought internet technology to only the most ardent enthusiasts before the nineties introduced that technology to the public. The 2000s effectively commercialized the technology as, though it already had become the .com (commercial) property we know, businesses were only just figuring out how to leverage the web.

The tech to market cycles to which Hoffman alluded.

Thus we find ourselves in the next cycle, in the 2000-teens, working through the next decade. Traditional industries such as energy, education, finance, and retail, having figured out what to do with the internet, are now asking what to do with the data.

Austin knows.

Austin’s Convergence of Big Data, Technology, and the Market for it

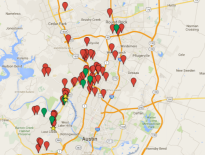

Not long ago, one of Austin’s most amazing and disruptive innovations, an analytics platform for PR, TrendKite, proved this convergence. Herein, a traditional form of media and marketing that most simply resigned to something forever immeasurable: Press. Earlier this year, Vast found venture capital validation for its autos and real estate data-as-a-service platform by way of Capital One Ventures. As we drill into specific industries, we find in Austin the significant and successful application of Social Data, Real Estate Data, Education Data, Financial Data, and more, to real world markets. Technology and market are converging in Texas to solve what we do with this data that has become available.

Nearly a year ago, I challenged Austin tech to refine our brand; to distinguish what’s unique about Austin’s application of technology to innovation. I posited that a similar convergence, that of the real world with technology, put Austin at the center of “where technology truly comes to life.” This collision of real world and technology in data is really no different; data is looking to meet Maslow’s needs, making Texas the bridge from Silicon Valley’s data foundation to real world application of big data analytics, intelligence, etc.

To put if frankly, it seems like Texas’ substantial non-tech industries are driving Texas entrepreneurs to innovate how the old world meets the new?—?and we’re doing that through data services.

I could think of no better way to point this out than to lay it out…

Austin’s love affair with consumable data might have started with Trilogy, or before, but that was merely the kernel of things to come, with our tech community today exposing data meaningfully through the likes of Rony Kahan and Kevin Kwast’s hiring work with Indeed as well as Andy Wolfe’s work to change recruiting through ROIKOI; what Ken Cho is doing at PeoplePattern; Richard Bagdonas and Zac Jiwa tackling health and medicine through MI7; cracking real estate through what Joshua McClure, Craig Hancock, and Jason Vertrees started with RealMassive and what Rick Orr is doing with RealSavvy; how Joshua Dziabiak and Adam Lyons are admirably taking on insurance The Zebra; how Chris Butler and Matthew Wilton are rethinking workforce data with One Model; Umbel unifying customer data sets thanks to Lisa Pearson, Higinio O., and Nick Goggans; the brilliant predictive modeling being done for our energy industry at Novi Labs; John F. Martin and the team’s work withInnography, cracking the code on intellectual property analytics; Vinay Bhagat and Alan Cooke providing intelligence to software buying decisions with Trust Radius; in education where Charles Thornburgh’s amazing team are bringing predictive analytics to Civitas Learning; how Chris Treadaway and team are using natural language processing to make social advertising work for brands at Polygraph; providing an understanding of audio and video is are Paul Murphy and D Keith Casey Jr at Clarify; and of all things, dealing with the impact of weather on supply chain we have Matthew Wensing work in RiskPulse, not to mention TrendKite and Vast, while continuing to bridge wide gap between the incredible data science and code, Austin has folks like John Heintz, Travis Oliphant, and Peter Wang tackling data platforms and infrastructure. Oh, and let’s not forget Brett Hurt, Bryon Jacob, Matt Laessig, and Jon Loyens who are “hatching something special” at data.world. That’s just a short list.

Collectively therein, hundreds of millions of dollars invested in Austin technology to make data consumable. Meaningful.

More exciting than that perhaps, in light of the challenges entrepreneurs face in raising venture capital is that this question of data is also being meaningfully applied to raising capital with the likes of Hall Martin, Damon Clinkscales, and myself, passionate about bringing market analytics and data to the venture capital economy so as to more effectively help entrepreneurs understand where, how, and when to raise capital.

Bringing meaningful data to new industries; but more than that, helping entrepreneurs of all walks, better connect with the right sources of capital. There might be enough data to say that Texas is uncovering the future of how we work.

great post, thanks Paul. lets stop talking about Big Data and make it power BIG ideas and drive products

It isn’t about big data, as it is much more about the small and critical insights that everyone misses due to the big data noise. Hence, what we do here at Zignal Labs, ensuring we can all stay ahead of what the world thinks.

One of the main problems with ‘big data’ (aside from it’s overuse as a phrase) is that the people who seem to have it also seem disconnected from the rest of the world in peculiar ways. We measure success in odd ways as well.

The true issue is giving all that ‘big data’ context – which requires that missing connection in so many cases. The other big issue is giving all that big data the right context instead of the wrong ones… and not extrapolating too much from it than the context should provide.

Data has never been the problem. Converting that data into usable and actionable information has always been the problem.

Very well said Taran. I was at Yahoo! nearly 20 years ago and when the idea of Big Data emerged, the insider joke was (and remains) that it was nothing new. The challenge and opportunity for entrepreneurs is not the data itself but the context and meaningful consumption of it – true as it’s always been.

Yahoo 20 years ago must have been quite an adventure. I miss those days; I was a young software engineer at Honeywell at that time.