Let’s make something clear before we get into it, this is a discussion of beer from the perspective of an entrepreneur and economist, to explain to you something critical to your startup ecosystem: “tech” is not code. It’s not apps, websites, VC-backed SaaS tools, or whatever spitting image of Silicon Valley nonsense is being peddled this week on LinkedIn (*ahem* myself excluded from that little criticism). Technology is applied invention. Startups are NOT the exclusive domain of “tech,” or rather, they are, but you’re wrong if you think that means hardware or code. Stop associating startups with code and at the same time, start recognizing that a startup is in fact distinct from a new business because of tech (or more accurately, innovation).

Before I go there, let’s make sure we’re on the same page, that tech is the wheel, it’s a new recipe, it’s the new method for blending chemicals, it’s a printing press, and it’s fermentation.

If you want an example of entrepreneurship that hits harder than your favorite hazy IPA, let me introduce you to the Celis family — a legacy of innovators so unrelenting in their mission that they smuggled yeast across the Atlantic to launch a tech startup in the form of a Belgian-style beer.

By the way, I have no idea if they smuggled the yeast in their socks or down their pants. I don’t even know if they technically smuggled it in, it just makes for a good story so go with it.

A tale of invention, loss, acquisition, resurrection, and generational determination. It’s also one hell of a case study for startup founders, economic developers, and anyone still thinking that tech only lives in a server room.

Back in 1966, in a tiny Belgian village called Hoegaarden, a milkman named Pierre Celis did something no one had the guts or the foresight to do: he reinvented a dying style of beer. Witbier, a cloudy, citrusy Belgian wheat beer, had vanished after the last local brewery closed. So, Pierre resurrected it from memory and experimentation, brewing in his father’s barn. That recipe, involving coriander and Curaçao orange peel, was tech — the kind of culinary innovation that laid the foundation for an entirely new market. This is a startup origin story.

Pierre’s creation exploded. By the mid-1980s, he was producing 300,000 barrels a year. But then tragedy struck: a fire gutted the brewery, uninsured. He sold to Interbrew (now Anheuser-Busch InBev), losing control of his baby — a story every founder should read or already fears with the same cold sweat of a startup swallowed by a legacy acquirer.

Funny thing that, in startups, knowing how and where you are going to exit, and being open to doing so, is a critical consideration of fundraising, and often the one overlooked by founders who assert they want investors but are unwilling to give up their company.

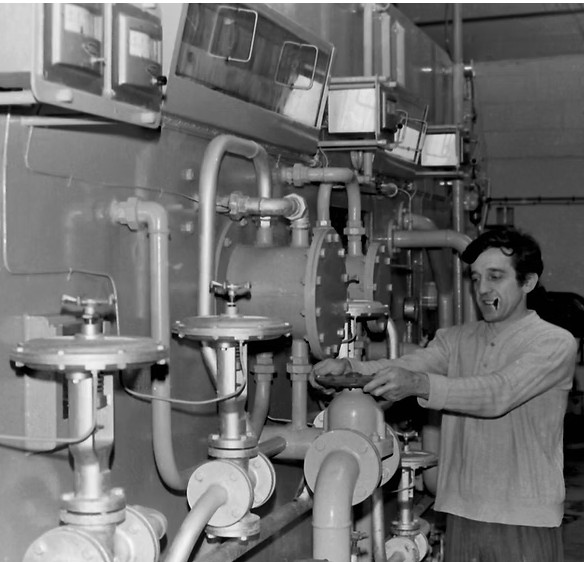

Now, here’s where the story gets sticky (yeasty?). Pierre, never the retiree type, smuggled vials of his yeast strain in his socks to the United States, specifically Austin, Texas. There, in 1992, at the age of 67, he launched Celis Brewery, again.

Let that sink in. This man — who had already built and lost an internationally known beer brand — picked up the pieces, crossed an ocean, and re-invented his brand in a foreign market. That’s not a business owner. That’s an entrepreneur.

Celis White, brewed in Austin, got rave reviews. Legendary beer critic Michael Jackson (the beer guy, not the moonwalker) gave it four stars in his “Pocket Guide to Beer.” And it wasn’t just a hit with critics: Texans went nuts for it. So much so that Pierre had to scale, and in 1995, he sold a majority stake, this time, to Miller Brewing Company, to meet demand.

And then came the classic mistake.

Miller mismanaged the brand, cut distribution, and by 2001, they shut it down (you could say, again). “It was horrible,” Christine Celis, Pierre’s daughter, told Austin Monthly. “We put our hearts and souls into creating something so beautiful, and then all of a sudden a big company comes in and shuts it down without regret,” Christine says, her accent colored by her Flemish background. “It was very hard for my dad. Very, very hard.”

Now, in any rational world, this is where the story ends. But entrepreneurship isn’t rational. It’s obsessive. It’s mythological. It’s the kind of madness that makes someone think, “Third time’s the charm.”

In 2017, Christine Celis did what any mission-driven founder would do: she got the damn trademark back and did it again.

Through a series of acquisitions after Miller shuttered the brewery, the rights to the Celis name and recipes bounced from Michigan Brewing Company (which also failed) to Total Beverage Solution. Christine negotiated to reclaim the name and legacy, securing the original brewing equipment and yeast strain — the same culture Pierre carried in his pocket — and reopened Celis Brewery in Austin.

But of course, nothing in startup life is ever smooth. In 2019, Celis Brewery filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Was it a failure? Only if your definition of success is short-term cash flow – which founders, it should never be. The brewery kept operating, the taproom stayed open, and the mission never wavered.

Today, Celis is brewing and distributing across Texas. And if you squint, this isn’t just a brewery. It’s a damn near perfect archetype of how real startup ecosystems work:

You don’t get startups from coding bootcamps. You get them from creative destruction — from people who give a damn. Celis wasn’t born out of a business plan competition. It was born from necessity, from culture, with passion, and from a willingness to do something different.

Think about it: Celis didn’t just bring Belgian witbier to Texas; they recreated the market for it in Belgium and then created it in the U.S. That’s startup behavior. That’s market-making. Its disruptive tech applied to food and beverage.

The lesson here for entrepreneurs, VCs, and regional planners salivating over the word “innovation” is simple: stop fetishizing software. Start understanding that innovation happens in every sector where people invent something new, do something better, or deliver something that the market doesn’t yet know it needs.

Celis was never just a brewery. It was a family-driven technology company operating in the medium of beer.

The next time you toast a glass of Celis White, remember you’re drinking the product of generations of founders, two corporate acquisitions, a somehow smuggled yeast strain, and a relentless drive to do something meaningful.

Yeah, a startup. And yes, beer is tech.

Don’t just drink the beer. Share the story. Share this article with someone who still thinks tech means code, and maybe, just maybe, they’ll start to see the real work that goes into building a startup economy.

Images grabbed from the Celis website, I hope that’s cool Celis!

Celis his exploits are well appreciated back here in Belgium too 🙂

A brilliant reframing of ‘tech’ and innovation through the lens of Belgian beer, proving that startups thrive on reinvention not just code and that true entrepreneurship is about relentless resilience, not just exits.

Great observation fairly consistent with the views of this new EU consortium: https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:7311528037299216384

Careful, Paul, you’re perilously close to becoming my new bff. Writing about innovation, entrepreneurship, AND beer?!? I also happen to have family in Belgium. But I digress…

Let’s start with this: “This man — who had already built and lost an internationally known beer brand — picked up the pieces, crossed an ocean, and re-invented his brand in a foreign market. That’s not a business owner. That’s an entrepreneur.” Yes. 1000 times yes. Not because he was obstinate, but because he saw a business opportunity AND created the market for it.

And this: “You don’t get startups from coding bootcamps. You get them from creative destruction — from people who give a damn. Celis wasn’t born out of a business plan competition. It was born from necessity, from culture, with passion, and from a willingness to do something different.” Why I hate hackathons and pitch ‘competitions’ in a nutshell. Nothing real and investable comes from them. Yay, big fake checks! No viable businesses.

Finally, “innovation happens in every sector where people invent something new, do something better, or deliver something that the market doesn’t yet know it needs.” The only nit I’d pick here is that I see innovation as applied (to a problem) creativity, and *entrepreneurship* as innovation applied to a business/market need. But the statement otherwise holds up.

I believe innovation falls on a spectrum

Idea > prototype > invention > technology > innovation > disruption

Where each is an application of the previous, putting technology in the middle, essentially just existing invention (no longer innovative nor disruptive, it just is).

Entrepreneurship I consider the bastardization of business ownership.

People took “entrepreneur,” which is actually a personality type, and since a higher % of entrepreneurs start businesses, Entrepreneurship came to inaccurately mean, “someone who owns businesses.”

Causation is not correlation and vice versa.

The fact is most business owners are not entrepreneurial and most entrepreneurs just work for a living.

Where I agree with your take, it is distinguished from say, adventurer, in that the context is market or business. But it doesn’t actually mean businesses – a person working at Dell who keeps trying to improve things beyond their scope, and even without permission or support, is probably an entrepreneur.

Well said Brian

I am looking into Irish innovation at this time. I like the taste better

Evgeny Galyaev yes! Brilliant. You saw my article from a few weeks ago? https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/how-irish-saved-entrepreneurship-paul-o-brien-9uzqc/

Paul: I like the definition of technology you cite in your post. “Applied Invention.” I recall reading another definition. “Applied Knowledge.” In either case, the point is clear: The contemporary use of the word “technology” as shorthand for information technology is completely myopic and misguided. Technology extends well beyond the boundaries of electronics.

Venture With Vision

Steven thanks

I frame it as:

Idea > prototype > invention > technology > innovation

Each being the practical application of the previous

Gérôme Vanherf ?

Obsession, loss, guts – and community. Celis was and is masterful at building community. I remember many a good afternoon rock show at the old brewery, and the new one is a great place hang out with people and sip a beer. I’m overdue to grab one out there with ensconced Celis community member Bob Karli.

Thank you for this excellently written and researched story. I lived in Amsterdam for 13 years and discovered witbier in 1995. It was all the rage in the 90s (still is in fact, it’s a staple). Hoegaarden is an actual brand of white beer. To this day, let the Germans poo poo this: Belgians make the best beer on the planet inho.

Love me some beer technology In copywriting world we’d call that the unique mechanism, but “tech” is such a cool way to put it too.

Spot on!

Great story (and writing)

Thank you.

Chris Sorensen cheers. Important to be reiterated, a lot. Our economy is struggling, and startup ecosystems are falling short because of the “tech” focus and misunderstanding about entrepreneurs.

Paul O’Brien yep! One of the biggest obstacles to entrepreneurship is the challenge of capital formation (fund raising).

Unicorn tech companies can raise capital from professional VCs. But everyone else has to raise capital from the (only) 10 million ” accredited” investors in the US (of which only a tiny fraction are active angel investors). We need to update the JOBS act to allow anyone to invest in anything. That would unleash a mountain of new capital that would fund millions of new startups of all types and sizes.

Brian Ellerman funny how necessity always seems to drive the best ideas. i’ve seen it firsthand… my biggest product breakthroughs came when i stopped chasing trends and focused on solving real pain points. curious, do you think culture or timing plays a bigger role in creating markets like this?