There’s a nasty little lie that keeps getting passed around the economy like a like a VC quote on LinkedIn: that every new business built on a new technology is a “startup.”

It’s how we got here, misunderstanding the difference between a startup and a business. The bloated graveyard of Web3 ventures, now being backfilled with AI “startups,” isn’t a cautionary tale about blockchain or metaverse, it’s a meaningfully clear signal we can’t keep ignoring or apologizing for disregarding, that most of what founders built weren’t startups at all; they were businesses in costume, trying to pass for startups because startups are sexy (supposedly). Sexy raises money. Sexy gets you tweets. Sexy gets you keynote stages and free t-shirts at the local Accelerator.

But sexy doesn’t scale. Sexy doesn’t survive when the hype dies.

The same thing happened with Web 2.0. It’s happening right now with AI. Founders jump on the innovation trend du jour and build products on top of it, mistaking the presence of a new technology for the presence of a new venture model.

Just because you’re using blockchain, AI, or quantum fairy dust doesn’t mean you’re running a startup.

Startups are not just new businesses. Startups are new business models.

They’re not “another version” of an existing idea with tech sprinkled on top. A startup creates an entirely new kind of economic behavior, often enabled by innovation but not reducible to it. It changes how markets operate, how customers behave, or how industries are structured. It breaks something, reconfigures it, and creates disproportionate value by doing so.

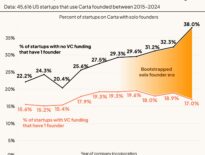

A fundable startup delivers 15x+ returns because it has to; otherwise, it can’t offset the 90% failure rate of the rest of the VC portfolio. In contrast, a business has a far more survivable model (about 54% fail), but it will never return what VCs need to justify the risk. VC isn’t being mean. It’s math.

And yet… the entire Web3 boom (and bust) was full of businesses dressed as startups begging for VC dollars. A therapy app using AI isn’t a startup; it’s a therapy app. A VR-enabled property showcase? That’s a design agency with a headset. A decentralized social network? Just another social network.

These aren’t bad ideas. In fact, many can succeed beautifully, generate wealth, and even exit. But none are changing the fundamentals of the business they’re in. They are businesses, and when they try to play the startup game, they not only mislead themselves, they poison the well for everyone else.

So, where’s the real failure? It’s not founders being ambitious. It’s mentors, investors, and the peanut gallery giving one-size-fits-all startup advice to people who are, in fact, building businesses. Advice like “focus on revenue” is classic. It’s what a VC tells a founder who shouldn’t be in a VC conversation at all. It’s not bad advice; it’s just not startup advice.

This perpetuates a myth: that startups should focus on revenue too. No, they shouldn’t, not in the early stages. Startups are in a race to discover scale, not to prove profitability. Revenue is a lagging indicator of value capture; scale is the leading edge of innovation (adoption of invention).

Founders keep getting told they’re doing the right things (revenue, retention, burn rate) but those things matter differently depending on whether you’re building a business or a startup. And that’s the line we’ve all stopped being able to see clearly.

So, how do you actually discern good advice from garbage? Here’s a litmus test:

- When someone gives you advice, ask them: “Thank you. Why?”

- If that checks out, press further: “Great. How do we do that?”

- Then, push again: “Wonderful. So we’ll do that. Here’s what we need from you.”

If your advisor can’t explain, assist, or participate, discount the advice. Not because it’s wrong, but because it might be. An investor says “focus on customers”? “Why?” “Great, how?” “Wonderful, give us half the funding we’re seeking and we’ll do that.” If they really knew how to help, wouldn’t they be offering intros, resources, or at least clarity?

Let’s look at two examples to make this real:

You want to open a crypto-themed restaurant that rewards loyal diners with blockchain tokens. That’s a business. Could be fun, could work (ha, maybe). But don’t call it a startup. You might get good advice, but the guy who mentors disruptive SaaS founders isn’t your guy because you are starting a restaurant and if that fails, you fail. Don’t mistake startup tips for gospel.

Now, imagine you’re building an AI fintech platform that integrates with credit cards and bank APIs to manage debt negotiation and repayment in real-time. That’s a startup. If your advisor gets it, they’ll offer something tangible: education, funding leads, a great connection, or maybe even a pilot partner (IF they know their advice is meaningfully valid).

In either case, the ability to distinguish a business from a startup (and qualify the advice you’re getting based on that) can save you years of wasted time, embarrassment, and missed opportunity. And frankly, it could save our entire ecosystem from continuing to burn cycles propping up zombie companies who were never supposed to be advised like startups in the first place.

If at any point in that advice validation discourse, the mentor or investor can’t explain or won’t help, discount their advice.

That doesn’t mean it’s wrong (it might be right), it means you have to discount it.

Why? How do I know you should discount it??

Well, work backwards. If I was giving you advice I *know” will work out for you… wouldn’t I help you in some way? Funding, resources, intros, or direct help?

If I know that my help is worthwhile, wouldn’t I be able to explain you how to do it? I’m not just regurgitating common advice; I know how to do it.

In either case, you have to understand how to discount or even dismiss what you hear by discerning the difference between business and startup.

I’d push through #3 in our fintech scenario because I work with startups. I wouldn’t always push through #3 with advice, I certainly don’t know everything. But I would with some of my advice because I know startups. And where I wouldn’t get to advice validation point #3, I’d be able to tell you how to do what I’m advising (or I wouldn’t advise it!) In turn, you’d know what to discard that I advise when I won’t go through the steps of validating my advice.

I would not survive validation of advice in our restaurant scenario because I don’t know how to make such businesses successful; and such things should be successful – we know how to make restaurants successful (I don’t but our economy does). Thus, you’d know to take my advice with a huge grain of salt while instead listening to the business advisors who work with restaurants.

What we should have learned from the implosions of early Web3

That overhyping a technology doesn’t build a startup.

That chasing capital without understanding venture economics is a fool’s errand.

That conflating innovation with invention or business is why so many smart founders wind up angry, broke, and bitter at an industry they never really understood.

If you’re going to play the founder game (whether you’re launching a new business or building a startup) you need to learn the rules. If what you’re building is a business, own that. Be proud of it. Just don’t cosplay your way into venture capital; it’s a model that isn’t designed for you. Because Web3 didn’t fail. We did, by refusing to admit that slapping a new technology on an old business model doesn’t magically make it a startup. It just makes it a business with new tech. And that’s okay, until you pretend otherwise.

Couldn’t agree more Paul O’Brien, and I believe this lack of clarity lies directly at the heart of a lot of the startup ecosystem failures we talk about. This reminds me of my favorite definition ever given for a ‘startup,’ which is (to paraphrase the great Steve Blank):

“A startup is a temporary organization in search of a repeatable business model.”

Note the complete absence of the word ‘technology’.

Thanks as always Paul, incredibly insightful.

The fact that we’ve deviated from Steve Blank on this is a better part of the reason why most startup ecosystems struggle along.

Thanks for sharing Andrew Steele

By the by… I’m in Phoenix for a couple weeks. I’ll dm you

If you’re trying to define a ‘start-up’ as what VCs are looking for then I can agree. But 99.9% of new businesses won’t qualify and, of those that do, 95%+ will fail. It’s a game invented by VCs for their own benefit. New businesses run for the benefit of founders, employees, and their customers don’t play this game. And they should be the focus of a start-up eco-system (that benefits the whole economy), not only what VCs want

Steve Jennis not sure I follow. I didn’t say the distinction has anything to do with VC – other than that VC seeks outsized returns and businesses don’t deliver that.

You often push on VC in my posts so let me ask you, what is the distinction of a new business from a startup? And, what is the expectation of and purpose of VC? Not that I disagree, I appreciate your comments on all my content; but you usually criticize VC so I’d like to know better how you distinguish everything.

Paul O’Brien I don’t see any difference between a new business and a start-up. Isn’t any start-up literally a new business?

If you’d like to talk over the terminology and my criticism of VC marketing, pls send me a DM. I appreciate your appreciation, and would welcome a chat.

Steve Jennis “Isn’t any start-up literally a new business?” Absolutely not, not even remotely similar. Didn’t read the article did you?

Paul O’Brien I simply disagree with your VC-inspired definition of ‘start-up’. I can only assume you are in the pay of VCs somehow.

Steve Jennis I’ve never defined startups that way, and you’ve read a lot of my work

Paul O’Brien The VC mantra is: raise, chase scale, worry about profitability later, sell me more cheap equity to keep going, don’t worry about control, sell me more cheap equity to keep going, now I want an exit for fund liquidity, you don’t agree – too bad, we need a new CEO to manage the exit, you’re diluted to nothing – too bad. If that’s what you call a start-up I don’t know any (sane) founders who’d want one. For me a start-up is simply a new business with several funding options…. and scale is chased only in the context of a path to profitability/sustainability. Disruption, new business models, disintermediation, unicorns, raising, Seed, Series X, etc.. is simply VC speak to tempt naive founders into their deal flow pipelines. My goal is to be an advocate for founder outcomes, not investor outcomes… for the 99.9% who won’t do better with early VC.

Steve Jennis agree to violently disagree. Kind of surprised, you’ve commented on most of what I’ve written so presumably you’ve read me… Never said startup = VC and frequently explained why new business != Startup. In fact, the entire premise of this article is the harm it causes to both kinds of founders when people refuse to distinguish the two, and you jumped at VC being the issue here.

What has you so adamantly against VC? Burned?

Paul O’Brien Not me personally, but many founders I know say that taking early VC was the worst decision they made.

If startup = new business model, where do infrastructure plays fit when they sell into the same workflows but collapse unit economics? Same behavior, new margins. What’s your real test: behavior change or margin structure?

totally agree but- I think it is a disservice to only use the term startup for the scale to VC model. Most businesses are established profit making engines that are very very different from a new (startup) business fighting to become consistently profitable. The distinction is crucial and I think there is an over glamorization of the VC model. Perhaps Startup(VC model) and Startup(Profit model)?

Keon Ha give me an example. Business model isn’t purely revenue and costs; being new, how that transpires is the key.

No reason infrastructure can’t be a startup and yet, if it’s merely creating an efficiency doing the same thing, it’s just invention applied in business.

Paul O’Brien Stripe wasn’t just cheaper payments. It productized compliance and aggregation so millions of internet businesses could exist without bank relationships. Same buyer behavior, new coordination layer. Is that the line for you, or does it still need visible behavior change?

Now if regions can focus on the MINDS that create new business models, recognizing them, their cognitive differences, fueling them with RELEVANT support needs instead of bogging them down with business-kindergarten…

Keon Ha I didn’t say anything about buyer behavior. Businesses existing without bank relationships is a new model, isn’t it? Granted, Paypal, but they merely enabled the same without a simple credit card transaction; Stripe innovated on top of what Paypal did first, and was a startup as such.

Something like Venmo, probably not a startup. Or maybe Venmo is, but Cashapp is just an iteration of that.

Paul O’Brien Fair point, I misspoke on buyer behavior. The distinction I hear you making is whether the model enables new market formation vs iterating within an existing one. That feels like a cleaner test than tech novelty or cost efficiency.

Paul O’Brien could one reason why founders continue to chase VC be that they see “business” ideas and teams get VC funding? For all the talk about outliers and power law returns, VCs continue to fund consensus and hype (not all, but a lot!).

VCs in a hurry to deploy capital and raise the next fund in a bull market, some following a spray and pray strategy … there are plenty of “bad” actors in VC land. It is no surprise that these mixed signals confuse founders.

What do you think?

Abhay my experience is *mostly* bad actors. I write about that a lot. Among our greatest challenges is Angels who aren’t, VCs who claim to be, Mentors who have no business mentoring, and Advisors who never worked in a startup.

What I’m learning from this post is to decide as a founder what game I’m actually playing, then design a model that mathematically belongs in that game.

What this clarified for me is that many breakdowns are not about competence or effort, but about misalignment between intent and structure. Different models obey different constraints. When those constraints are ignored, even good execution compounds in the wrong direction.

The real discipline, then, is not chasing validation too early, but resisting advice that locks the shape before the behavior is understood. Some guidance accelerates discovery. Other guidance freezes assumptions. Knowing the difference becomes a strategic skill, not a moral one.

I can confirm that as is exactly what happened to me when trying to launch an EdTech startup, and took me almost 2 years after the money dried and the team left to understand that what I had was a business. It solved a problem for an specific customer but the technology was irrelevant in that solution. Now at the distance is evident but I failed to understand it then at the resonance box that incubators sometimes are

Leseli Mothae yes…. except perhaps, that a new business is a new business and a startup is a startup; there is no decision to be made about which you want to be – that’s like saying you’re an orange because you want to be, even though you’re actually an apple.

The mistakes perpetuated are found in that people allow these lines to be blurred. Causing mentorship, advice, and investor engagement, to get involved and mislead when such engagement is meant for the other.

Paul, this breakdown is spot on. The distinction between a new technology and a truly new business model is something many founders miss, to their detriment. Scale vs. profitability is a significant mindset shift that needs more attention in the startup community. Appreciate you sharing this. Always open to connecting.

It’s interesting how often startups confuse new technology with a new business model. A strong point: success requires changing behavior and scaling, not just a flashy product or hype.

Paul O’Brien I’ve lost years chasing the wrong metrics!

Thanks so much for sharing my friend

Paul O’Brien I think we’re closer than it reads. I’m not saying founders get to choose what they are. I’m saying they often don’t realise how differently the same new business is interpreted by mentors, investors, and operators.

When that isn’t made explicit early, advice meant for one path gets applied to another, and that’s where I’ve seen things go wrong. Your post helped me see that more clearly.