Cities everywhere are doing a lot for entrepreneurs, often sincerely and impressively, and what I’m finding in city after city is that the greatest opportunity is not in another startup program or even fostering a new investor but building capacity. They are supporting some founders, but not more founders. They are helping some investors, but not bringing new capital into the market. They are delivering programs, but not producing system-wide throughput.

Talk to economic-development teams in New Mexico, Alberta, Queensland, Lisbon, or Tulsa and the pattern sounds uncannily familiar. They’ve launched accelerators, pitch competitions, public–private task forces, grant programs, and “innovation districts.” Yet their deal-flow density stays relatively flat, their mentor pools age out, and their best startups outgrow the region long before the region grows into what they need.

The problem is not that cities aren’t doing enough. The problem is that cities aren’t expanding their capacity to serve more of the entrepreneurs, mentors, and investors that a competitive economy now requires. As Brookings has pointed out in their analysis of innovation clusters, ecosystem performance is a function of network depth, institutional coordination, and resource density. Resource density is the giveaway. Most cities don’t lack activity; they lack density, coordination, and the infrastructure that makes tens of thousands of entrepreneurial decisions possible each year.

The OECD, likewise, concluded that capacity building must focus on enhancing entrepreneurial support systems, strengthening intermediary organizations, and improving human capital pipelines, particularly in regions seeking to diversify their economies.

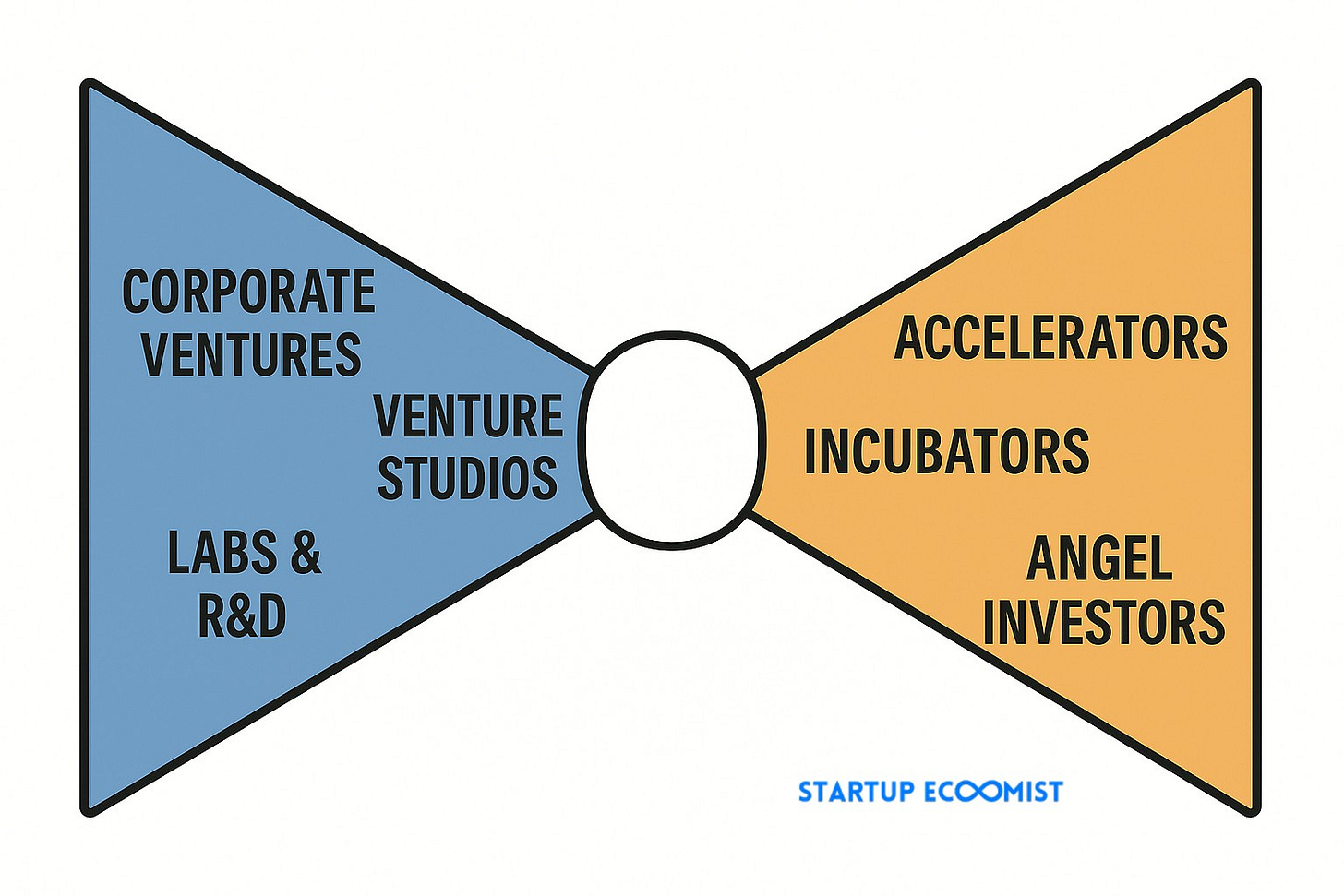

And that’s the paradox. Cities are building things that look like startup ecosystems, while the underlying throughput resembles a two-lane frontage road at rush hour. Most communities still collapse at the knot of the bow tie; the point where early-stage aspiration is supposed to transition into real growth. Most cities simply don’t have the lanes, the exits, the signage, or the on-ramps necessary to move hundreds of founders through to market traction, capital formation, and scale.

Capacity building is the hard, unglamorous engineering work of widening the freeway.

Let’s talk about the ten dimensions of entrepreneurial capacity that economic-development leaders must confront.

Article Highlights

- 1. Overcoming Silos: shared infrastructure, shared memory, shared momentum

- 2. The Missing Middle: the widening gap between nascent startups and established companies

- 3. Funding the Actors: not venture capital for startups, but stable, multi-year support for ecosystem builders

- 4. Measuring Outcomes, Not Activity

- 5. A Culture Where Collaboration Is Normal, Not Negotiated

- 6. Include the Invisible Talent Not Just the Visible Founders

- 7. Architect Environments Where People Perform at Their Highest Potential

- 8. Align Government, Academia, and the Private Sector (the knot in the bow tie)

- 9. Accelerate Innovation by Unlocking Local Competitiveness

- 10. Adapt Global Best Practices (don’t copy them!)

- The Freeway Analogy to Share with Your Economic Development Team

Ecosystems stall because information moves slowly, repetitively, or not at all. Universities run their programs. Chambers run theirs. Accelerators build cohorts in a bubble. Government agencies maintain parallel databases. Everyone “supports entrepreneurship,” yet founders navigate a maze where every door leads to a different map.

Silos destroy throughput.

MIT’s Regional Entrepreneurship Acceleration Program found that ecosystems with strong collective governance and shared infrastructure outperform those where actors remain isolated. Shared infrastructure means, for example, a common CRM for founders (why not?), collective storytelling, unified mentorship standards, and consistent deal-flow pipelines.

What to do: create a single interface for entrepreneurs; treat every organization as a node in one network rather than one more isolated program. Better? Obligate that startup development organizations in your ecosystem are promoting one another, freely sharing all mentors and investors, and referring founders to the resources more ideal than perhaps their own (or shut them down because they’re contributing to the silos that limit entrepreneurs)

2. The Missing Middle: the widening gap between nascent startups and established companies

Economic development traditionally focuses on small business support and corporate attraction. But between those poles sits the high-growth, pre-scale firms that need mentorship, capital, and technical support long before they qualify for incentives or bank financing.

High-growth new firms are responsible for a disproportionate share of net new jobs. Yet these companies often die in the gap between ideation programs and investor readiness. That gap is exacerbated by what are likely other middle gaps also a challenge in your ecosystem such as capable marketers, mid-career jobs, and Series A funding, just to name a few of the commonly cited gap issues in cities throughout the world, “we have stuff on this side and for that side but nothing can cross the chasm.”

What to do: build mid-stage supports such as B2B customer access, fractional executives, applied R&D partnerships, and capital-readiness preparation.

3. Funding the Actors: not venture capital for startups, but stable, multi-year support for ecosystem builders

Every ecosystem quietly relies on a handful of people: connectors, mentors, operator-founders, nonprofit teams, program managers, analysts, community architects, marketers, and scouts. Most are underfunded. Many burn out. Some quit in exhaustion because no one supports them.

The National League of Cities concluded that sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems depend on sustained investment in intermediary organizations and local leaders.

Cities pour millions into corporate recruitment incentives while asking ecosystem builders to charge $25 tickets to a startup event just to keep the lights on because the local law firm won’t sponsor any more than a few thousand dollars.

What to do: provide multi-year operational funding, not short-cycle grants; treat ecosystem builders as infrastructure, not event planners.

4. Measuring Outcomes, Not Activity

Events are not outcomes. Demo days, pitch competitions, and hackathon participation are signals of interest, not economic performance.

Capacity building requires metrics tied to throughput, such as:

- funding per capita

- new angel investors activated per year

- number of scalable startups reaching $1M+, $5M+, and $10M+ revenue

- local corporate procurement awarded to local startups

- exits and liquidity events

Ecosystems obsessed with activity create vanity metrics that move no capital, change no culture, and mislead policymakers. What matters is whether you can repeat success.

What to do: adopt metrics tied to growth, traction, and capital formation, then promote those stories relentlessly to create gravitational pull.

5. A Culture Where Collaboration Is Normal, Not Negotiated

Collaboration often dies in the same place innovation does: at the boundary between organizations competing for relevance, credit, or funding.

Stanford’s research on ecosystem performance shows that trust and informal collaboration networks are strong predictors of early-stage innovation output. Yet many cities treat collaboration as a memo instead of a habit.

What to do: build rituals that force cross-pollination such as shared mentor pools, cross-organization cohorts, integrated communications channels, and standing ecosystem roundtables. I’m revisiting consideration #1 a bit to reiterate that it’s on you to require this of startup development organizations (and don’t take their word for it that they are, ask the people you’re supporting in #3 because they’ll tell you about the bad actors)

6. Include the Invisible Talent Not Just the Visible Founders

Most ecosystems empower the people already on stage: serial founders, credentialed executives, alumni of recognizable companies. But the OECD warns that untapped entrepreneurial potential disproportionately exists among people outside established networks.

I see this all the time where over a decade, the same handful of people repeatedly win your annual awards, are featured in local press, and give the speeches and panel talks. You’re not recognizing the leaders, you’re ignoring the majority that matter.

What to do: broaden discovery. Never limit the stage to members or paying partners. Build outreach teams. Use founder-assessment tools rather than resume filters. Ensure “openness to outsiders” (the trait the best ecosystems have in common).

7. Architect Environments Where People Perform at Their Highest Potential

Entrepreneurship is not merely a function of talent; it is a function of conditions. Workspace design, mentorship availability, early customers, access to prototyping resources, and even psychological safety determine whether a founder moves fast or stalls.

Environmental context determines the likelihood that entrepreneurial intention becomes entrepreneurial action.

What to do: build spaces, norms, and tools that remove friction from every step, from IP support to B2B sales to freely available physical space to mental-health support for founders.

8. Align Government, Academia, and the Private Sector (the knot in the bow tie)

Government moves slowly, academia moves cautiously, and the private sector moves according to incentives. Alignment requires shared outcomes, shared data, and shared language.

This is precisely where most ecosystems break, as I explored in a bow tie analogy. Cities invest in “on-ramps” (programs, workshops, accelerators) but fail to tighten the knot where founders transition into revenue, customers, and capital. Universities produce research without commercialization pathways. Governments offer incentives but not deal flow. Investors wait until traction exists, long after the region has lost half its would-be founders.

What to do: implement a single strategic operating framework such as what we have in Founder Institute for cities, define shared KPIs across all partners, and appoint ecosystem stewards with authority to coordinate across institutions.

9. Accelerate Innovation by Unlocking Local Competitiveness

Regions rarely understand their own comparative advantage. They chase whatever trend is hot so as to appear innovative (crypto conferences, AI hubs, Web3 zones, biotech corridors) rather than building around the strengths their talent, industries, and institutions already offer.

Pace-based innovation succeeds when it aligns with regional industrial capabilities and existing knowledge domains.

If you’re saying, “tech sector,” you’re doing it wrong because tech isn’t a distinction.

What to do: map local industry clusters, commit to two or three defensible strengths, and build founder services tailored to them. Focused ecosystems outperform generic ones.

10. Adapt Global Best Practices (don’t copy them!)

Cities love to import templates: “Let’s be the next Austin.” “Let’s go with that partner because they’re dominant in Silicon Valley.” “We need an accelerator like Boulder.”

But ecosystems are not software; they are organisms. Best practices must be adapted to local cultures, industries, risk profiles, and political realities.

Founder Institute, MIT REAP, Startup Genome, and countless global partners consistently emphasize this: the regions that rise are not the ones that copy, but the ones that translate.

What to do: study global models, borrow only the principles, and rebuild the implementation from the ground up for your city’s realities.

Most ecosystems have the same problem as most metro freeways.

Insufficient on-ramps.

A couple of exits but rarely in the ideal places.

Lack of transit alternatives while everyone is clearly angry at the congestion.

And signs that confuse newcomers while locals pretend it all makes sense.

Capacity building is freeway engineering: widening lanes, adding ramps, improving exits, synchronizing signals, and making sure the entire network handles volume, not just special-occasion traffic.

Until a city treats its startup ecosystem as infrastructure, not programming, it will always end up with congestion, frustration, and a whole lot of talent taking the first exit out of town.

If your region is running out of lanes, consider this an opportunity to rethink the infrastructure before the next wave of entrepreneurs decides to merge somewhere else.

As always brilliant content!

Thank you!

The things that actually create results for economic development are the things are not “glamorous”. Develop your talent. Give them access. Improve your mentorship. Build a playbook for your city, don’t copy someone else’s.

Jonathan Greechan exactly

Your insights here are a powerful reminder of the importance of building capacity within our ecosystems, Paul!

In fostering collaboration and breaking down silos, we can create environments where entrepreneurs thrive.

Let’s focus on empowering every founder, mentor, and investor to drive meaningful growth together. The journey may be challenging, but the potential for transformation is immense! ?

The frequency with which I hear in cities, “silos” as a major problem, should be very troubling to everyone.

Paul O’Brien yes – very troubling!

Well said Paul O’Brien — Austin has been backsliding severely over the past 2 years on many of these fronts…I worry this message might be too late for the local ecosystem at this point

re: Ecosystems stall because information moves slowly, repetitively, or not at all. Universities run their programs. Chambers run theirs. Accelerators build cohorts in a bubble. Government agencies maintain parallel databases. Everyone “supports entrepreneurship,” yet founders navigate a maze where every door leads to a different map.

Silos destroy throughput.

Somewhat off topic but I’m mentioning it because recognition of the pattern might be useful.

Long to short, in the middle of the recent government shutdown a publication in my area published a list of non-profits involved in “food insecurity” (read: getting food to the people who need it). The list was 10 to 12+ entities long.

Most on the list I recognized, and many had other causes / missions.

Why? Why so much redundancy? Why the lack of partnering? Why do many silos?

Are we all wired to believe – falsely – that we and only we can build a better mouse trap? Wouldn’t be easier to say, “Hey Paul, I see you’re in the ______ business. We’re interested in that as well. How can we help you? To help us?”

It boggles mind mind how much waste there seems to be.

/rant

Mark Simchock when in Austin, John Zozzaro used to chuckle with me that the “Live Music Capitol of the World,” has dozens of non profits for musicians (duplicating efforts while slicing up resources so none have enough) all while at the same time, the city lacks a truly meaningful music industry.

Short-term funding/initiatives lead to short-term activity bubbles – that measure the wrong things. e.g. founder appreciation isn’t tracked, but pitch competitions are. It should be driven by customer (i.e. founder) satisfaction, and as 99% of founders never raise VC, raising is almost irrelevant. As long as an ecosystem is built to support VC it will fail 99% of potential and actual founders. VC may, but rarely, become relevant much later in the lifecycle of a start-up, but that isn’t where founders need help. Ecosystems should focus on founders who are bootstrapping to PMF and profitability, not the <1% who work for VCs (and of whom 95% will fail). A VC-only focus is toxic to a start-up ecosystem, and that’s why they mostly fail.

Everything you just wrote about is exactly why I built mitolabs.ai like to a T. The system we are walking out of was artificial, which is why mitolabs labs puts missions, people, processes and projects at the forefront, and powers it with resource Activation protocols. Think you would really appreciate what I’m trying to do here. And I want meaningful advisory. Thanks for sharing.

You’re absolutely right! Nice to have, but are you equipped to navigate and support?

Great points, Paul O’Brien. You can look at any city that thrives today in entrepreneurship, and you can timeline exactly how each of these capacity steps emerged.

Here in Austin, go back 50 years and most of this was missing. Forty years ago MCC arrived. Then Sematech. Then the slow build of funding partners. Each layer only worked once the ecosystem had enough maturity for it to create real value — and for people to trust it.

Ecosystems don’t transform because of programs. They transform because the underlying capacity reaches a point where founders, capital, and institutions all benefit from participating.

Keep it coming!

• Wade Allen would be really intriguing to plot histories against a framework like this and see if there are elements that changed that clearly had a greater impact than considered.

Very well-put. We are having the same, each and every, the same issues in Luxembourg. Did you, by a chance, published the article on LinkedIn? I would share

Certainly is on LinkedIn too so you can share, Taisiya

Good discussion going on there too: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/why-startup-ecosystems-fail-scale-economic-playbook-capacity-o-brien-jpzzc/

Mark Simchock people have a scarcity mindset and don’t want to collaborate. They fear if they collaborate, others will still a funding source, a client,etc. In the nonprofit sector, they are already limited capacity so it would make sense to do so. Until funders require collaboration it will still be siloed.

Tarsha Hearns, EDP I don’t disagree. But those in the startup sector should know better at this point.

But then again, I suppose this aligns with Paul O’Brien long running theme of why so many so-called startup efforts aren’t working – they’re not actually doing startups. They’s doing start-overs. Start-overs, by defintion means they got nothing new and they’re looking to compete directly in red oceans instead of seeking blue ones.

Mark Simchock Tarsha Hearns, EDP it also reflects my other recurring point that if people are looking for a lucrative career, they’re not going to find it working in startups.

That, that scarcity mindset is very valid, but living it, harms the entrepreneurs, and makes it more difficult for anyone to make enough. And so… What? Well, yeah, clients do get stolen, funding sources are fickle. That happens anyway.

When the clients pay market rate, that scarcity mindset isn’t as much of a problem because the competition causes the service provides to have to be better.

Startups aren’t that. They don’t pay market (shouldn’t). They aren’t successful with some standard business playbook executed. So we have a different scarcity issue: there isn’t enough money, so the people who can’t ensure there will be more,b really just shouldn’t be working in startups anyway (they’re not going to earn what they want).

Remove the startup inexperienced. That removed the waste that haunts startups. It focuses the expertise in fewer hands, who are then properly paid for, and who drive better outcomes for the startups (growing the pie).

Innovation won’t come from the center of the ecosystem; it will come from the margins.

The riches are, and always have been, in the niches.

Everything listed here is true for business owners who benefit from standardized programs, cohort-based learning, and repeatable playbooks. But the startup founders driving real innovation? They don’t fit inside canned programming, prescriptive education, or linear pipelines.

Founders arrive with wildly different cognitive loads, trauma histories, support gaps, executive-function patterns, and life constraints. Treating them as interchangeable units inside a programmatic system is exactly why throughput doesn’t improve. You don’t “activate” the next wave of innovation with more workshops; you do it by scaffolding humans, not forcing compliance to structure.

What regions miss most is that high-potential founders need personalized infrastructure, not more programming.

If cities want more scaling companies, more fundable founders, and more durable local IP, they have to stop chasing uniformity and start investing in the “invisible talent” you called out; the people whose brilliance is trapped under collapse, caregiving, coercive dynamics, disability, or isolation.

Excellent post. Here are my thoughts on 1,3 and 5.

1. Mapping roles and interdependencies can expose the gaps and redundant efforts. I have been a part of two resource mapping efforts by neighboring cities. What I found interesting was that many of the resources on each map were duplicated by each city.

3.Stable, multi-year support for conveners, connectors, and builders is essential to resource the organizations that hold the ecosystem together. I led a citywide ecosystem initiative that had a 3 year runway for funding. When the funding dried up we struggled to get it renewed beyond 1 year follow on funding. Why? I think it is because we were more successful at measuring activity and not outcomes.

5. Collaboration takes trust, mutuality, and interdependence by design. My lesson learned after leading an ecosystem initiative is to teach the actors “HOW” to collaborate. Multiple people coming together on a shared purpose that they normally do on their own requires facilitating collaboration. It’s like being an only child for many years and now having to share and play with a sibling.

I think it all starts with having conversations. You have provided great actionable advice to guide these conversations.

Tarsha Hearns, EDP your last point is everything – it always comes down to poor communication, in some way.

Outstanding piece, Paul. I have thoughts on all 10, but will limit my comments to 2 and 3. As this isn’t my first rodeo, I designed XLR8 to support the “high-growth, pre-scale” companies you mention in 2 exactly because it was missing. However, I have been massively disappointed in the lack of government support for our program (and most others). Two years in, they continue to claim they hadn’t budgeted for it. Speaking of, I’d argue item 8 is the other side of 2: not enough talent and funding going toward the translation of commercialization into real market traction.

Good points made again dude and #4 is the jewel. Coalescing and identifying regional investors at scale and building those metrics is one key.

One thing I’ve found is that cities & regions are overly protective rather than collaborative.

Founders and investors need exposure to other founders and investors beyond their ecosystem. They need to stop thinking “I” and think more “we”.

All ecosystems beyond our own doorsteps have those similarities you speak of.

Our community spans four continents.

It introduces investors to innovation and deal flow that better educated and informs what they do at home. For founders it gives them a global outlook and contact book that allows them to see opportunities and learning from other founders elsewhere.

That’s what accelerates the skills and growth of founders and investors from what I’ve seen. More of this, and more startups outside the traditional hot houses get invested in and grow.

My note to local government, education and accelerators is, “if you really love it, set it free”.

lots of good points but I have reservations about ecosystem wide standards. often by the time the politics have fought their way out the “standards” are meaningless or counterproductive with no flexibility to them. each stakeholder tends to be in love with their own view of the world. for example, I am not a fan of FI’s but it may be a good match for some. better actual coordination without death by committee would be great–

Love the article and totally agree with everything! Have seen these factors play out so many times and this is why ecosystem-building gets a bad rep from potential funders including large corporations. The problem is that even when corporates, policymakers, donors and other funders set out to improve the ecosystem, they fund one or two pieces of this puzzle, leaving the rest to chance. For example, sure, the connectors must receive multi-year funding but in the absence of outcome metrics and engagement of invisible talent, all you get is more innovation theater.

Nishi Viswanathan, MD, MBA +

ecosystems are though to build, but once they are strong and steady, they create sooo much long-term value.

None of this matters if people don’t adopt the basic finance principles behind venture ecosystems.

Here is a meaty 10 points for leaders to heed. A bit of self assessment and insider critique is healthy.

Always spot on Paul O’Brien or at least spurring great debate

Lauren M. Postler, MSSW Jerry W Jones Jr.

I question where local ecosystems make sense and where learning happens better when it’s not limited by location. Location is important for finding local customers – and employees if you’re in office or hybrid. Yet, a lot of the connections made by startup programs focus on mentorship and investment – situations where domain fit is more important than location.

Tara Raj local makes sense because relationships matter; otherwise, I agree with you… too many make the mistake of thinking anything local is better or good enough – usually something remote is better.

Incredibly helpful, thank you for these insights!

Capacity building is crucial for truly fostering entrepreneurship. Without the right infrastructure and collaboration, we lose potential innovators.

Paul O’Brien Jonathan Greechan The beautiful truth is that every city is unique and can play to their strengths.

Honored to join you and Sameer in this conversation, Paul—sometimes ecosystems confuse motion with progress. This session is a needed chance to dig into how capacity-building, aligned systems, and long-term support can unlock sustainable economic growth rather than just another round of headline activities.

Steve Jennis yes