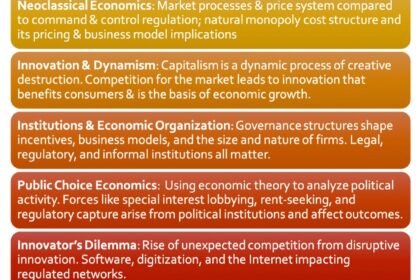

Having recently discovered Lynne Kiesling, my attention was drawn to Northwestern University’s Institute for Regulatory Law & Economics‘ Five Prisms, which she shared online and which I’ve included here (granted, without asking, I hope they don’t mind).

Economic regulation in our rapidly changing world faces challenges I find legislators and local leaders ill equipped to consider: the shifting winds of markets, the unstoppable march of technological innovation, and the ever-evolving whims of policymakers trying to catch up. The Institute for Regulatory Law & Economics (IRLE) has been digging into how we can make better, more legitimate decisions in regulation by recognizing that the ground beneath our economic systems is always moving. To help us understand and navigate that movement, they created this framework known as the Five Prisms of Law & Economics Analysis.

Imagine the Five Prisms like a superhero team. Each one sees the world a little differently, but together they help us spot opportunities, threats, and unexpected outcomes in industries that are heavily regulated (like utilities, transportation, or healthcare) and, I worried, even startups. While they were originally designed to analyze public utility regulation, as I read the model, insight for entrepreneurship struck me and though I’ve not spoken with the Institute, with Kiesling, or dug much deeper than the surface of what’ readily available, I was curious if we could apply it to startups.

And yes, I said “worried,” as regulation tends to be a burden or hurdle to entrepreneurship, or rather it’s considered, it’s also a spark to innovation since entrepreneurs tend to disregard rules in order to fix something regardless of what might not be allowed. I was curious if it made sense to use the framework to find those opportunities, threats, and unexpected outcomes in our startup ecosystem – to help us avoid, better craft, add, or remove regulation. With me, let’s meet the Fantastic Five (according to my assessment) …

1. Neoclassical Economics This is your traditional econ class in action: supply and demand curves, cost structures, marginal benefits. It’s the spreadsheet-and-whiteboard model that tells us how much something should cost, who will buy it, and how much will be made. In regulated industries, it helps explain natural monopolies; like why only one company wires your electricity. For startups, neoclassical economics shows us how to identify inefficiencies or underpriced value, and why understanding marginal costs in a digital business (spoiler: they’re near zero) changes everything.

2. Innovation & Dynamism Static models are great but the ground shifts. Enter Schumpeter’s famed “gale of creative destruction.” This prism acknowledges that markets are not frozen in time. We live in an age of constant flux where yesterday’s unicorn is tomorrow’s Yahoo. Innovation creates new markets, rewrites business models, and obliterates regulatory assumptions. For entrepreneurs, this prism should be the flashing neon sign that says: disrupt or die (another spoiler? most of you fail because you ignore this).

3. Institutional & Organizational Economics Markets don’t exist in a vacuum, they’re shaped by rules, laws, habits, and contracts. This prism looks at the role of institutions, not just in government but in the way businesses organize themselves. It explains how the structure of production (like vertical integration in utilities) gets challenged by tech advancements (like solar panels or software-as-a-service). For startups, this is the lens that reveals how legacy institutions and outdated laws might inhibit innovation — or offer the exact friction point where your disruption can wedge in (hence my point that most of us go around regulation).

4. Public Choice Economics This prism pulls back the curtain on how politics and economics intertwine. It’s not just about markets and models, it’s about people. Voters. Lobbyists. Regulators. Public choice economics uses economic theory to understand political decision-making and how incentives get warped by rent-seeking and special interests. Which is why, even if your startup can out-code and out-market your competitors, you may still be out-lobbied. Policy and regulation aren’t just background noise, they’re a battlefield hopefully evident in how quickly governments go after the latest hot potato (now, AI).

5. The Innovator’s Dilemma Here’s where Clayton Christensen’s work joins the party. Why do big companies, with all their resources, fail to adopt disruptive innovations? Why did Blockbuster shrug off Netflix? This prism explores how incumbents often get crushed by tech they didn’t see coming, because they won’t afford the risk involved, or which they simply ignored. Startups thrive in these gaps, but also in risk building atop fragile network architectures or regulatory blind spots. It’s also where network effects (think Uber or Airbnb) can either catapult you into a monopoly or bury you under a pile of lawsuits.

Applying the Five Prisms to Startup Economies

Startups don’t exist in a frictionless vacuum of innovation. They operate in economies laced with regulation, legacy systems, and political agendas. So how does this five-prism view help us better work as the entrepreneurs that we are, or guide regulators if they legitimately want to support startups?

Neoclassical Economics: Here we learn to treat startups like value engines. Understand cost structures, pricing power, and consumer demand. Startups that get unit economics wrong are toast. This prism helps us answer: is there actual profit potential or just wishful scaling? It asks whether you’re creating real surplus value or just gaming the arbitrage until someone else builds a better spreadsheet.

MoviePass offered unlimited movie tickets for $10/month, ignoring basic neoclassical economics by pricing far below their costs and losing more money the more people used the service. They failed to understand unit economics, creating no real value; just subsidizing demand with investor cash and hoping scale would fix the math. The startup didn’t build a better market; it distorted one and collapsed under the weight of its own economic delusion.

Innovation & Dynamism: Our startup economy lives and dies here and everything about entrepreneurship depends on understanding change, timing, and where the next wave is crashing. This prism warns us to stop playing by rules written in 1998. Don’t build a music streaming startup on CD-era licensing logic. It dares us to ask: are we truly innovating, or just digitizing yesterday’s model?

Clubhouse is a perfect example: it exploded in early 2021 by offering live, drop-in audio chats, seemingly riding the wave of pandemic isolation and the podcast boom. But instead of building toward where the world was going (hybrid work, algorithmic discovery, asynchronous content), it clung to a fleeting moment and an outdated, radio-like model with zero lasting infrastructure. Innovation & Dynamism reminds us that chasing hype without evolving with the market isn’t innovation, it’s nostalgia dressed as disruption.

Institutional & Organizational Economics: This is where the good stuff hides and where I often hammer the critical role of marketing: startups must understand the infrastructure and institutions they’re trying to change. That’s not just tech — it’s schools, zoning laws, banking charters, and decades of precedent. Want to disrupt healthcare? You better understand insurance billing codes. This prism tells startups: map the system before you try to burn it down.

Theranos promised to revolutionize healthcare diagnostics but completely misunderstood (and ignored) the institutional infrastructure such as FDA approval, insurance reimbursement protocols, and clinical lab regulations which govern medical testing. They built flashy tech without integrating into the system they claimed to disrupt, failing to grasp that in healthcare, you don’t have a choice but to play along. Institutional & Organizational Economics teaches us that disruption without systemic understanding isn’t innovation, it’s malpractice.

Public Choice Economics: We’d love to believe in the meritocracy of the market, but this prism says: get real. Founders must engage policy, not just pitch decks. Why do some apps thrive while better ones die? Often, it’s who called the Senator (or VC who could). Entrepreneurs must learn to navigate government relations like they navigate UX. Accelerators, economic development boards, and even university research centers shape the playing field more than your codebase and I’ve seen countless startups fail because they drank the cool-aid that some customers were the key to success.

Uber didn’t just disrupt taxis with an app, it won by lobbying aggressively, rewriting local laws, and leveraging public opinion to outmaneuver regulators and unions. Competitors with better tech or safer models often failed because they didn’t play the political game, assuming product alone would win (see my previous criticism of customer adoption). Public Choice Economics reveals the ugly truth: in startup success, policy influence often beats product elegance.

The Innovator’s Dilemma: Startups are disruptive until they’re not. Understanding this prism means building for resilience. Be paranoid. Assume giants will co-opt your features. Patents and IP? Ha. Expect what you’re doing will be copied. Bet on architecture (APIs, interoperability, modular systems) that can outlast trends. And always look for the cracks in incumbents’ armor caused by their own success. Network effects are only your friend if you become the hub.

Snapchat pioneered disappearing messages and vertical video, but Instagram, backed by Facebook’s scale and data infrastructure, cloned its features and crushed its growth trajectory. Snap’s innovation wasn’t protected by IP—it was vulnerable to replication by incumbents with better architecture and deeper networks. The Innovator’s Dilemma reminds startups that disruption isn’t enough; survival means building systems too adaptive to be swallowed.

How Startup Founders Can Hijack Utility Economics to Build the Future

Lynne Kiesling is the economic mind behind this entire framework. A professor at Purdue and long-time scholar of energy policy, she works in how regulatory decisions can either fuel or choke innovation. Her work (which you can explore more at lynnekiesling.com) reveals how markets, institutions, and technology collide in the real world. Think of her, I think, as the economic philosopher-engineer who handed startups a new compass.

Startups and their allies — investors, incubators, policymakers — must adopt a more mature, systemic lens. We must stop treating entrepreneurship as a pure hustle game and instead embrace what the Five Prisms illuminate:

- Build with unit economics in mind (Prism 1), not just virality.

- Ride the waves of disruption but understand the tidal forces (Prism 2).

- Study the system you’re disrupting with the care of a surgeon, not the rage of a revolutionary (Prism 3).

- Influence the system, don’t ignore it (Prism 4).

- Design for durability and anticipate displacement (Prism 5).

In other words, if your startup isn’t accounting for these Five Prisms, you’re not building a business. You’re just building an app.

And if you are building with these in mind, then it’s time to demand that your Representatives, local economic development board, a public affair consultant such as myself, the local accelerator, and the VC funds do the same.

Start asking the harder questions: Who are you lobbying? What assumptions are embedded in your business model? What happens when the market changes? And how will your company thrive in a world of shifting rules, evolving institutions, and relentless disruption?

Because we’re not just entrepreneurs. We’re architects of the next economy. We create the jobs, and we must step it up and do so.

The IRLE framework also uses experimental economics as an experiential learning method. The program provides policy-relevant learning materials, and its flagship event gathers state regulators and staff together for an annual 4-day Socratic workshop to study and discuss the economics of closely-regulated network industries, bringing a clear theoretical framework in law and economics to actual regulatory practice.

Regulation are often a symptom of Crony Capitalism. While they’re meant to present as if they’re in the public’s best interest – and sometimes they are – there are often other financial winners – and losers. Sure, like them or not, regulation are a form of scarcity. You might as well accept them (for the most part) and from there identify and exploit the opportunities – if there are any.

Regulations are create fragile. Startups – by your definition – should be anti-fragile. That is, where are the as-yet-unseen holes in the regs?

Mark Simchock I tend to push the fact that crony capitalism only exists because there is a crony in office – when people want to criticize it, it’s important that they appreciate that the capitalisms are (for the most part) merely playing by the rules required or bent by lawmakers. It’s not the capitalist in whom everyone should be angry, it’s the legislator.

Which is to say, I think (though I think you have some typos in your last though, so I’m not sure), what entrepreneurs/founders fail to appreciate how significantly they must play by those rules and with those lawmakers. I have a follow up in mind to write, that if we think about it, I suspect all the major disruption of the last 15 years or so has been contingent on the government – ridesharing, short term rentals, AI, mobile devices, social media…

I’m inclined to propose that startups need someone in Public Affairs more than Product Management ?

Lynne is brilliant. Very cool to see her get a shout out.

So I’ve learned. Hope you’re well Max!