Nations that adopted startup-friendly policies mid-1990s or early 00s, and consistently implemented effective measures, are now reaping the rewards; seamlessly transitioning into digital economies and enjoying long-term benefits. Conversely, those that dragged their feet on economic development of startup ecosystems are now grappling with how (and in my experience, for the most part, are failing, trying to do it themselves).

The prosperity of economies and the well-being of future generations hinge on making substantial and immediate investments in building robust startup economies.

Article Highlights

Startup ecosystems have become the primary engine of economic growth worldwide

Enter the APEXE Report—G20 Pilot from Startup Genome and the Global Entrepreneurship Network. This report isn’t a doorstopper; it’s a unique toolkit designed for development and innovation entities and national government agencies to cultivate startup ecosystems. It introduces the first-ever balanced scorecard to evaluate a country’s effectiveness in converting its innovation potential into startup ecosystem performance, a process aptly dubbed “Lab-to-Startup Conversion.” Additionally, it provides a strategic guide to inform future policy action.

Startup ecosystems generate immense value by creating novel products and business models that spawn jobs, enhance corporate competitiveness, drive economic growth, and tackle social challenges. For a city, a portion of this value can be quantified by its startups’ ecosystem value (EV)—a standardized measure created by Startup Genome to benchmark local startup ecosystems. While GDP measures production rather than asset value, the ratio of EV to GDP serves as a useful gauge, revealing significant variations across the G20.

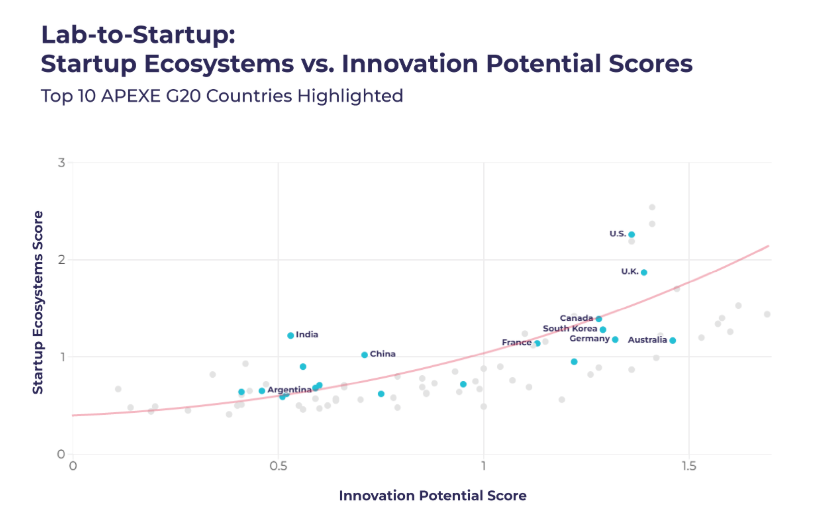

Take a look at the chart they put together. In R&D and most innovation rankings, both South Korea and Germany frequently rank among the top in the world, as do Australia, the U.K. and the U.S. But if you’ve followed me for long, you’re well aware that I push us to appreciate that tech, venture capital, or innovation, alone, are misleading indicators of entrepreneurship and the potential for founders to create jobs. Hence my interest, and hopefully yours, in this methodology, also looking to a Startup Ecosystem Score, which seems to reveal accurate where the rubber hits the road (with both measures plotted).

The Innovation Potential Score captures factors quantifying and influencing traditional innovation, including patent production, talent quality, economic strength, corporate fabric, and business-friendly laws, reported Startup Genome. While I’d vehemently argue that patent production is not a positive indicator of entrepreneurship, I realize that’s a contested question. APEXE also provides a scorecard of a country’s recent startup policies and initiatives against best practices codified by Startup Genome over the last decade. These practices are based on insights measured, advised, and learned from 85 ecosystems in 45 countries, including the world’s top performers.

The disparities between leading and lower-performing countries represent substantial opportunities. If the underachieving G20 nations could elevate their EV/GDP ratios to the average, we could witness, according to Startup Genome, an astounding $2.7 trillion surge in ecosystem value within the global startup economy. But how can we assess the extent to which countries are maximizing their potential for startup performance, and what steps can they take to improve?

The APEXE Report offers a meaningful perspective on startup ecosystems at the national level, establishing another data-driven, reproducible framework to help countries evaluate their startup policy actions, identifying how they can unlock innovative entrepreneurship by assessing how effectively they utilize their potential.

“Our scorecard of startup policy action – which can be considered a leading indicator or “vector” of future startup ecosystem performance – shows South Korea now slightly outperforming Germany thanks to its investments in startup policies and initiatives,” wrote JF Gauthier and Christopher Haley, both of Startup Genome, with World Economic Forum. “This suggests South Korea’s Lab-to-Startup position should improve in the future and earn it a final APEXE rank of 5 versus 9 for Germany.”

Which is referring to the final G20 APEXE ranking (a score), each of which is then broken down into multiple dimensions to provide an actionable scorecard for policy action.

Now, let’s address the elephant in the room: the role of creativity and the so-called “creative class,” as well as what might (or should) comprise that Startup Ecosystem Score. Countries like China and India, despite their massive populations and burgeoning economies, often struggle with innovation. Not for lack of talent or resources, it’s arguably due to cultural and systemic factors that stifle creativity. In contrast, nations like France and Germany, while rich in culture and history, face challenges in their startup ecosystems. Bureaucratic red tape, risk-averse mindsets, and rigid structures can impede the agility and innovation that startups require. You can see the implication of that on the chart, in comparison to the U.S. and U.K.

The research is brilliant, and I’ve been geeking out on the methodology for the better part of the day. But if you’ll join me, I’d like to do that here too, dig into the ecosystem measures, seen to the right, because I fear they are based on outcomes largely defined by the success of the United States, then what we might also consider.

Notice that the Performance of the ecosystem seems overweighted toward later stages, and while normalized relative to GDP, that creates a rub in that late-stage funding or exits at a relative size, are very subjective of the costs of an ecosystem. It’s troublingly evident just in the United States that founders and investors in Silicon Valley tend to have higher expectations than most other U.S. cities, in large part due to nothing more than the relative cost of living. The same challenge, thus, applies comparing country to country.

And that’s not to say they overlooked it; I’m digging into this as week speak and merely noting that the Performance measures seem to value larger size / later stage, and that measure might be a misleading equivalent.

Funding is another curious measure to dig into further. We all know too well that the raw number of VCs (or Angels) can be a dangerous assessment since such people are often self-defined, or we lack consistency in what it means to be active.

I hit a red flag with Talent in seeing Github developers; if we’re distinguishing startups as requiring software development, we have a problem.

Still though, it might be fair to say that on the whole, with innovation taken into account along with the other indicators of the ecosystem, the quantity of software developers may simply correlate well with the volume of successful startups overall.

Startup Ecosystem Performance

- Performance: 40%

- Ecosystem Value by GDP

- Count of exits over $50M by GDP

- Count of exits over $1B by GDP

- Late-Stage Funding amount by GDP

- Number of unicorns by GDP

- Funding: 35%

- Number of early-stage funding by population

- Amount of early-stage funding by GDP

- Number of new active VCs

- Number of VCs with exits

- Talent (Experience): 15%

- Github developers

- Startup experience (number of Series A rounds by population)

- Scaleup experience (exits over $50M)

- Global Reach: 5%

- GC: Inbound Score

- GMR: Outbound Score

- Programming: 5%

- Number of accelerators and incubators

Leaving us with two scores I’d criticize as being weighted too little. Global Reach should be far more substantial, as we see throughout ecosystems in the U.S. that the perception founders have about being globally disruptive vs. locally validated, changes everything. An ecosystem that isn’t oriented globally is all but irrelevant save for the rare exception that breaks out of the norm. As for Programming, I can speak from experience that this measure needs rigor because many such programs are self-titled, most are poorly run or lack curriculum, and we can all point to a program that is clearly more of a problem than benefit; and yet, more than most of what’s here, to have an ecosystem, we need these Startup Development Organizations in place.

What Cities and Countries Should do to Foster Startups

Granted here, my take, drawn from what I’ve been digging into the APEXE Report—G20 Pilot and my own work and experience consulting for governments:

- Adopt and Sustain Startup-Friendly Policies – Cities and countries must commit to long-term, startup-focused economic policies, rather than short-term, politically convenient gestures.

- Reduce Bureaucratic Barriers – Heavy regulation, risk-averse mindsets, and excessive red tape suffocate startups. Countries like Germany and France suffer from this, while South Korea’s aggressive policy shifts enabled rapid ecosystem growth.

- Invest in Early-Stage Capital Access – Funding must be plentiful at the seed and early stages, not just for unicorn-chasing venture capitalists. As you should know, this calls for drawing it (explained here), not pushing for it.

- Develop High-Quality, Creative Talent, Not Just More STEM – Measuring ecosystem health by the number of engineers is misleading. Countries need experienced founders, marketers, storytellers, serial entrepreneurs, and startup-savvy professionals.

- Encourage Global Orientation – Startup ecosystems that think locally instead of globally are doomed to irrelevance. The best-performing ecosystems study the market globally, assess competitors everywhere, cultivate global networks, and serve customers from anywhere.

- Reevaluate What ‘Performance’ Means – And I’m not saying this of my assessment of the APEXE methodology, I am saying this to you all – reevaluate YOUR measures of performance. Most cities celebrate # of meetups, having a startup hub, and that incubators are holding demo days, stop it, those are vanity measures.

- Support Effective Startup Development Organizations (SDOs) – Incubators and accelerators are crucial, but too many programs are selling services with no real impact. Support should be tied founder success far greater than average.

- Measure and Adjust Policies Using Real Data – The APEXE framework provides a balanced scorecard for evaluating startup ecosystem health, awesome regardless of my questions and concerns! Use it. Governments must track and refine their strategies based on actual performance, not headlines and public sentiment.

- Foster a Culture of Creativity and Risk-Taking – China and India struggle with true innovation because of cultural and systemic constraints. Innovation flourishes in environments where failure is acceptable, and creativity is nurtured.

- Make Founders the Priority, Not Institutions – A startup ecosystem isn’t about venture capital firms, research institutions, or government agencies patting themselves on the back. It’s about empowering entrepreneurs to build, fail, and succeed.

And one more, a big one which I’ve talked about a lot: Specialize, rather than trying to be the next Silicon Valley, startup epicenter, or tech hub.

For a deeper dive into the APEXE Nations Report and its implications, you might find their launch webinar insightful:

Take a look at https://www.linkedin.com/posts/joemilam1_with-the-new-sovereign-wealth-fund-its-activity-7292588776759996417-xxu-?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop and https://bit.ly/4dJRxK3

Cheers Joe. One of these days, my market driven worldview and your financial worldview needs to come together to work out the manifesto about this stuff. Perhaps over blackjack and cigars.

ready when you are…..

As Mr Spoke would say… Fascinating.

Now let me play Devil’s Advocate (in order to provoke some thoughts and conversation).

Let’s presume this study’s score is wrong, or at least not exactly right.

What if it’s a numbers game? In terms of population, that favors India and China. That is, they have more bodies and minds to throw at any given startup idea / experiment.

What if scarcity breeds innovation (and we know it does), then again that favors India and China. They’ve come up, but they’re still hungry, literally.

What if you don’t have to be “global” but you can be “significant” by focusing on a couple of markets; and those markets are… wait for it… India and China?

While I do agree there are cultural issues that have an impact, do those continue to apply as younger generations – in India and China – get exposed to other ideas, possibilities, ways of thinking, etc? Then what?

My gut says this study has a bias and that bias violates the rule: Past performance is no indication of future results. Put another way, if that diagram swapped the US and the UK with China and India heads somewhere would roll.

The single biggest thing the USA can do to enable entrepreneurs is to make healthcare affordable / free. imho

Mark Simchock good questions and, I think the numbers are wrong; not terribly so, I just think they’re a better reflection of successful startup than startup ecosystem and innovation potential.

Still, numbers game? Except that China has been that threat for decades, it doesn’t work out. It’s cultural, because China has a culture that averts risk in order to adhere to the political doctrine, and copies, because, technically, it makes a hell of a lot of sense to just copy existing technology and keep up (patents be damned). Changing that is a cultural shift not seen since Mao forced it.

On healthcare, we agree. The country is becoming unaffordable to live, merely exist, and when that happens, people won’t take risks because they can’t.

As a long-time angel investor and someone leading a (hopefully well run) scaleup program without curriculum, clearly I have a vested interest in this discussion. By my reading, later stage performance is not overweighted, or at least not improperly so. We can do all the “ecosystem building” and idea pitches we want, but at the end of the day the economic impact needle is moved most by the larger rounds leading to scaling (job growth) and exit (leading to recycling of capital). Put another way, I could continue the “spray and pray” practices many angel groups still encourage, but prefer to work closely with downstream investors to understand their requirements because an exit following my investment is highly unlikely, whereas following theirs is most typical.

Brian Ellerman my concern Brian, is while your approach is sound and practiced in what works well, most cities are flush with those angel groups and spray and pray approaches. I’ve floated about 3 dozen different incubators, and most of them are nothing more than so-named coworking spaces with meetups and occasional speakers.

You may be right, that later stage performance is not overweighted, it’s just an observation. Still, the marketer/economist in me can’t help but see methodology used and when I have first-hand experience with the fact that the data is inconsistent, we know the conclusions are off somehow.

Appreciate you.

Love this