Entrepreneurship has long been celebrated as the ultimate engine of economic growth, innovation, and job creation. But what if the fervor surrounding “being an entrepreneur” has gone too far? The glorification of entrepreneurship as an end in itself may actually be hurting our economy. As with most cultural phenomena, the truth is more nuanced than the mantra that entrepreneurship is universally great. It’s a word that has taken on a life of its own, often conflating the skills and desires of business ownership with the restless drive to create and improve—traits that may not align well with long-term economic stability.

At its core, entrepreneurship should not be synonymous with business ownership. Instead, it’s a quality that speaks to risk tolerance, the drive to improve, and the willingness to push boundaries, often at a personal cost. But popular culture’s transformation of “entrepreneur” into a status symbol has inspired waves of would-be founders who may lack the resources, experience, and intrinsic drive to succeed. Let’s explore how this trend could actually harm the economy and what we misunderstand about entrepreneurship.

Article Highlights

The Misconception: Entrepreneurship != Business Ownership

The word “entrepreneurship” today evokes images of tech founders, media personalities, and billionaire business owners. But historically, entrepreneurship referred not to the act of owning a business but to a specific set of personality traits: resilience, a high tolerance for risk, and a fixation on improvement without necessarily seeking permission or resources. Entrepreneurs push boundaries, and their work, whether successful or not, drives incremental improvements, inventions, and innovations. But these are pursuits often fraught with failure.

Most true entrepreneurs are not business owners, and conversely, many business owners lack the personality traits that define an entrepreneur. But with the rise of startup culture and platforms that glamorize the entrepreneurial journey, more people than ever are convinced that they must be entrepreneurs to make a mark. Kevin Roose, an economics journalist at The New York Times, once wrote that “the startup world has conflated the idea of an entrepreneur with a founder or a CEO, which misrepresents the essence of entrepreneurship.”

What we have now is a wave of people, encouraged by pop culture and social media, aiming to become entrepreneurs without fully appreciating what that entails. The reality is harsh: about 60% of new businesses fail within five years, more, among startups – expect that 90% of all attempts fail. This failure rate increases for entrepreneurs, who, driven by their nature, often tackle ambitious, risky ideas without a roadmap for stability.

The Economic Toll of Entrepreneurial Glorification

When society glamorizes the entrepreneur, it unwittingly inspires people who may lack the intrinsic qualities of an entrepreneur to pursue a path they aren’t well-suited for. Many people desire the prestige of being a successful founder, not the grueling journey it often entails. They don’t necessarily want to create something new or disrupt industries; they want the image, the recognition, and the validation.

In the process, the economy suffers. The high failure rate associated with entrepreneurial ventures can be a significant economic drain when inexperienced or ill-suited individuals pour resources into doomed ventures. As Inc. columnist Tom Eisenmann points out, “a misguided perception of entrepreneurship as a way to easy fame and fortune leads many into starting ventures that ultimately damage their financial and mental well-being and place strain on the broader economy.”

Universities have added fuel to this fire by offering degrees in entrepreneurship, promising young students the keys to a future of independence and influence. But can you really “teach” someone to be an entrepreneur? Certainly, one can learn business, marketing, and finance. But the qualities that make someone an entrepreneur—those inherent traits of risk tolerance and creative disruption—cannot be taught. As economic advisor Scott Shane has noted, “Entrepreneurial traits are more likely to be personality-driven rather than skill-driven, and the mistaken idea that anyone can learn to be an entrepreneur is dangerous for the economy” (The Entrepreneurial Instinct, 2011).

The issue extends further when we look at mental health: entrepreneurs are more prone to financial strain and mental health difficulties, in part because their nature compels them to take risks and because society often marginalizes those who think differently. Their high tolerance for risk and failure can result in repeated financial and personal setbacks, even as they continue to push for new ideas. This reality contradicts the “entrepreneurship as freedom” narrative, pointing instead to a life of instability for many.

So, Is Entrepreneurship Bad for the Economy?

Not exactly. What’s harmful to the economy isn’t entrepreneurship itself but the glorification of the “entrepreneur” identity without a clear understanding of its challenges and implications. Paul Graham, founder of Y Combinator, has famously stated, “It’s not the idea of entrepreneurship that’s hurting the economy, but rather the romanticized misconception of it.”

True entrepreneurs do add immense value to the economy. Their innovations, while fraught with risks, drive job creation, efficiency, and even whole new industries. But their contributions often come at their own expense. These individuals, who are intrinsically motivated to improve systems and processes, don’t do it for fame or recognition. They do it because they can’t imagine doing anything else.

But when we confuse being an entrepreneur with being a business owner or a startup founder, we lose sight of the real purpose and value of entrepreneurship. The term “entrepreneur” is tossed around so freely that it risks becoming a catch-all for anyone who starts a business. Yet the economy needs both entrepreneurs and stable business owners, each bringing their unique strengths without trying to become something they’re not.

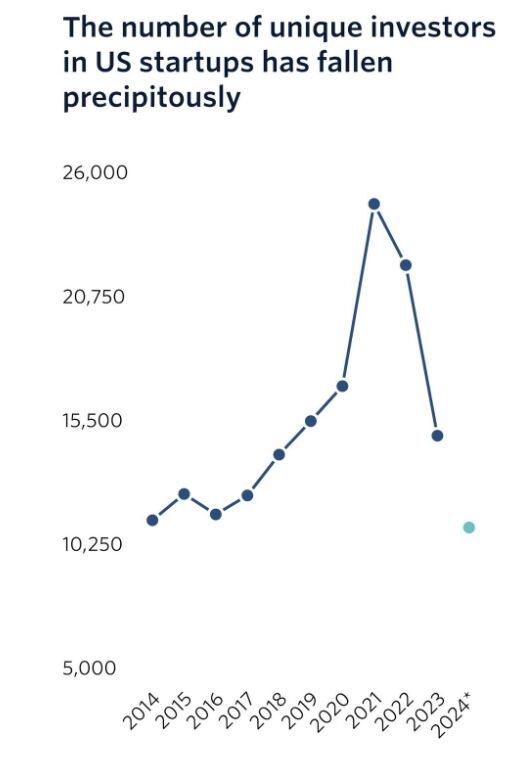

Entrepreneurship, in its essence, is not bad for the economy. But its hyped image—the “celebrity entrepreneur” culture—can have damaging effects, leading many astray and resulting in a significant economic cost. This year, Jason Lemkin and SaaStr pointed out that the number of active VCs is down, significantly; if we want to harness the true power of entrepreneurship, we must develop our ecosystems distinguishing those driven by the entrepreneurial spirit from those who simply seek the accolades. The economy depends on both but thrives only when each contributes from a place of authenticity and genuine purpose.

Paul, what does “Duciness” at the top of your first graphic mean?

A. W. (Bill) Kleinebecker it means that AI can’t spell

re: ” the startup world has morphed “entrepreneur” into a title we slap onto anyone who takes a risk, without any thought to what they’re actually doing or why they’re doing it.”

The word has lost it’s meaning. But I don’t believe the legit startup world did it. The word has been “re-appropriated” by the masses for the masses. It’s no different than 90% of the “CEOs” on LinkedIn.

I beg to differ on many points you summarized here. Especially when media puts forward attention grabbing titles of ‘Entrepreneurship hurting the economy’.

In my opinion that topics is wide and deep and has many nuances, plus the bad entrepreneurs fall naturally out of the selection quite fast. Equally one can say that economy full of domain and (yet stale) established companies is hurting the economy.

Neither extreme is good, and no need to feed students a fairy tales of being entrepreneurs or virtues of climbing the ladders in the corporate world.

Ariana Smetana No meaningful disagreement from me

For some, the extremist headline is meant to get clicks… for others, it’s to be controversial and viral… for me, it’s to make people think and start a meaningful discussion.

A challenge though (I run incubators), bad entrepreneurs don’t naturally fall out of the selection fast; in fact, it’s generally consistently agreed that one of the challenges of a place like Texas (affordable and encouraging, relative to the coasts), is that it doesn’t cause people to fail out fast but rather enables people to hold out far too long. I just explored that a bit here: https://seobrien.com/rethinking-startup-ecosystems-to-build-what-investors-really-want

Well-said, Paul! Entrepreneurship is the ability to gain Knowledge, Skills, Abilities, and Other essential skills (KSAO) while eating lentils for a while so you can enjoy steaks for the rest of your life!

Hormoz Mogarei KAOS

Love it!! Thrive in kaos so we can serve others

I’d suggest it’s like a sport, you can get better with practice and coaching, but if you don’t have the natural ability, grit, and aptitude it won’t help much. In fact, a coach taking cash from someone who doesn’t have ‘the right stuff’ is misleading them at best, and probably exploitating them for monetary gain. It’s not quite that entrepreneurs are born, not made; but that is much closer to the truth than the opposite.

Steve Jennis it’s a natural inclination from what I’ve seen. But those characteristics you mentioned are innate. You can’t teach grit and perseverance. These are individual traits that people have or they don’t .

Loneliness at the top is a silent struggle, but building authentic relationships and prioritizing self-care are essential for long-term leadership success.

Another great article!

Paul O’Brien Bootstrapping is the purest form of entrepreneurialism. VC-funded distortions (e.g. some accelerators) need to be considered just that before you can determine the ‘health of a start-up ecosystem’. 99% of viable businesses today never needed VC cash, those that survive on it are clearly not (yet) sustainable.

It’s worth considering that the same hustle culture glamorizing entrepreneurship is often what drives people to overlook essential skills like sales and marketing. Being a technical founder with a great product idea is only half the battle. Remember, Steve Jobs once said, “Great things in business are never done by one person.” Building a sustainable startup isn’t just about coding or tech innovation; it’s about understanding your market and selling your vision effectively.

Instead of chasing the title of “entrepreneur,” focus on building foundational skills that help you connect with customers and sell your idea. The best entrepreneurs are not just builders but also storytellers who can sell their story to investors, partners, and most importantly, customers. By grounding yourself in these fundamental skills, you’re more likely to create something lasting rather than just jumping into the startup race for its own sake.

Mark Donnigan it’s increasingly being repeated that the best founders are storytellers

The Bright Side:

Jobs for All!: Entrepreneurs create new businesses, meaning more jobs and less unemployment – a win for everyone!

Sparking Innovation: Entrepreneurs’ fresh ideas keep the economy on its toes, driving growth with exciting products and services.

Healthy Rivalry: Competition among entrepreneurs ensures you get better products, competitive prices, and a brilliant customer experience.

The Flip Side:

Resource Hogs: Entrepreneurs might not always use resources wisely, potentially hindering growth in other promising sectors.

Startup Woes: Many startups bite the dust, leading to job losses and wasted resources.

Economic Rollercoaster: The rise and fall of startups can add to economic uncertainty, affecting investors and stakeholders alike.

Precisely Dina Obita (https://www.quora.com/profile/Dina-Obita-1)! No one is suggesting entrepreneurship *is* bad, but rather that we’d be wise to better appreciate the negative implication as much as society tends to encourage that everyone should be an entrepreneur.

Thank you for shedding light on a thought-provoking perspective about entrepreneurship. Your insights into the distinction between genuine innovators and those merely chasing accolades open the door for an important conversation—how can we better support and recognize true entrepreneurial talent in today’s economy?

Thank Mark! One of the most notable answers is an answer that too few want to actually into practice – Oxford University, the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) and the University of Melbourne, studies 22,000 startups and found a very high correlation between certain personality traits and success (around an 80% correlation).

Which is to say, just as the data proves definitively that failing Marketing is a leading cause of startup failure (and yet founders generally just won’t prioritize it), we know with near certainty which types of people will succeed. My observation is that society doesn’t want to discern that so greatly, because it excludes many; it’s discouraging rather than encouraging.

The thing is, the only reason to encourage people who are very likely to fail, to try, is to monetize them in some way. Mark Simchock drew my attention to the idea of the Startup Industrial Complex, which indeed exists, to turn people into entrepreneurs so they can be monetized with coworking space, SaaS, and paid advice.

https://seobrien.com/success-as-a-startup-founder-a-desire-for-variety-and-novelty-an-openness-to-adventure-reduced-modesty-and-heightened-energy-levels

What if it were the federal government being the driving force based on the needs of the “people” based on an assessment of best of breed of the various solutions. There are such “competitions” waged today in the U.S… such as responding to a DoD bid.

Paul O’Brien based this article you posted here, I agree there is a distorted view of what entrepreneurship is. Mostly this was driven by VCs and accelerator ecosystems which are hyping funding vs building solid and sustainable companies based on customer cash flows. This distrotion then reflects on founders who take money and do not fulfill the lofty VCs they desired growth. But there are many others who are selfunded and want to growth organically with customer base but do not get any “glory” of what media sees as success of valuation. Nonetheless, this topic has many angles to explore. These are some of my experiences.

Ariana Smetana Yes, very often exactly the wrong thing (raising) is the most celebrated by the start-up hype machine. Personally, I would like to see bootstrappers hailed as the real entrepreneurial heroes (raisers should be celebrated too but only after they secure a healthy return for themselves and their fellow founders). One big problem is that VC is assumed to be necessary for entrepreneurial success, from the founders perspective I’ve found this to be the exact opposite of the truth – it’s customers that are necessary (and they are the best investors too).

Paul O’Brien Interesting. Thank you for sharing.