In most of the world, startups are in disrepair. No more effectively can we just reboot or defrag a computer to actually fix it, than we can try again and again to host demo days, networking events, and run incubators, expecting different results, when there is a virus in the system. Begging the question, that, while we can tell if a coworking space or a single startup program is helping founders therein, can we determine macroeconomically if the ecosystem is working well?

This becomes important when startup ecosystems reach a tipping point where traditional markers of success — like high company formation rates, pitch events, and press coverage — fail to correlate with real economic impact. In startup ecosystems, distinct from the economy at large, we have to appreciate that impact of success on founders can’t be discerned by jobs created, revenue, or office space consumed, because were that to be sufficient, economic development offices would merely focus on growing businesses (or attracting companies) that accomplish that goal while startups struggle. Startup ecosystems have to create conditions that align with how successful ventures are developed, rather than encouraging founders to chase activities that sound impressive but don’t translate into long-term value.

Here’s what you might see in your city, warranting a look at what’s being done and the metrics determining success:

- Increasing Startup Failure Rates

As ecosystems mature, high startup failure rates may expose weaknesses in the existing approach. If ecosystems are producing lots of companies but seeing fewer succeed past initial funding or traction stages, it reveals a lack of focus on sustainable, iterative development. Investors and policymakers would start to see that the “startup hype” doesn’t lead to real growth without deeper, product-centered support. - Investor Fatigue and Capital Flight

If local investors become fatigued by backing early-stage startups that consistently fail to mature or scale, they may begin diverting funds to regions or sectors with higher success rates. This loss of capital signals an economic risk for the region, pressuring ecosystems to refocus on building companies that meet investor demand. When investment begins to flow outward, local stakeholders recognize the need for a fundamental change. - Mismatch Between Investor Needs and Founder Development

Venture capitalists increasingly seek startups with proven product-market fit and scalable models, rather than those simply making a splash in the local media or on social platforms. As the gap grows between what investors want and what founders deliver, ecosystems will feel the pressure to reorient their efforts. Founders who haven’t built viable products can struggle to raise later-stage funding, stagnating growth across the ecosystem. - Policy and Economic Development Goals

Local governments and economic development agencies may begin prioritizing policies and funding focused on economic resilience and job creation, rather than just startup activity. When policymakers see that startups are struggling to deliver the anticipated economic benefits, they may push for policies that foster long-term product development, sustainability, and investor alignment, which make for a more robust economy. - Cultural Shift Toward Sustainable Growth

Finally, if startup culture begins valuing vague impact metrics over lasting, disruptive, global impact, ecosystems will fail to remain competitive, while those that don’t will start to lag. Ecosystems in this new wave will be incentivized to adopt frameworks and programs that genuinely prepare founders to build lasting companies, leading to a broader cultural shift.

When examining the economic development of startups, viewing startups as analogous to products offers an insightful lens through which we can assess the effectiveness of a local ecosystem. In this framework, venture capital (VC) investors are the primary customers, and the local ecosystem’s ability to deliver startups that align with investor demand becomes a critical metric of success. Therefore, understanding product development—what it requires and what it doesn’t—can help determine whether local ecosystems are supporting or undermining entrepreneurial success. The relationship between VC trends and startup ecosystems should reflect a clear product-market fit: if the ecosystem is robust, we should see increased local investment, signaling that investors find value in the “products” (startups) being developed.

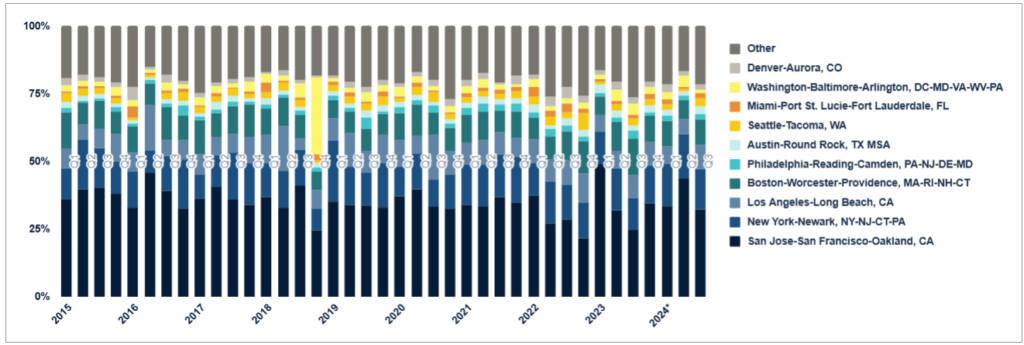

It that helpful? Take a look at this trend of venture capital investment by major ecosystem in the U.S. and tell me, if cities are growing and effectively developing startups, as seems so for many places, should venture capital investment not follow?

All of this, from the Q3 2024 Pitchbook-NVCA Venture Monitor, which you can download here.

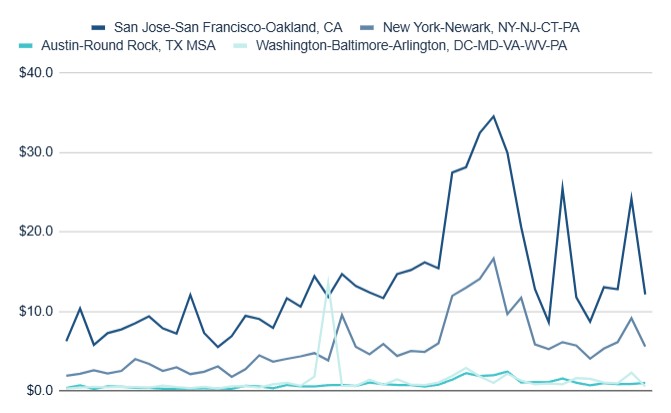

So much data can make it a little difficult to tease out my observation here so let’s take a subset of popular cities and reduce the chart to only the four.

To look at how Pitchbook rolled up so much, you might be tempted to say that everything appears flat; in instead let’s look on Silicon Valley, Austin, Washington DC, and New York.

The peaks find our economy in 2021 / 2022 which, absolutely worth appreciating, falls in the middle of the coronavirus quarantine period that ran from late 2020 through early 2023. Arguably, this might reflect the appreciated fact that venture capital investors are rather like philanthropists, and when times are difficult or opportunities emerge, they help through funding – and yet, if and when challenges persist, or returns fail to manifest, they have to pull back (they can’t invest what they don’t have).

Couple thoughts…

- Claims of Silicon Valley’s demise. Real or hype?

- How many 7-year cycles (the typical time it takes for venture capital investment to start delivering returns) should we go through before we can expect substantially greater investment from the yields?

- Is it right to eventually expect that with the growth of a region, increase in support programs, and global attention, we would see venture capital investment increase to take advantage?

Article Highlights

Startups as Products

Startups are, at their core, products designed to solve specific problems. Just like any physical or digital product, a startup must go through a process of validation, iteration, and market testing before scaling. Richard Florida, a leading urban theorist, once noted that “startups are not just firms; they are experimental units of economic development.” This framing implies that the process of building a startup is inherently similar to developing a product. Startups require multiple rounds of iteration, customer feedback, and refinement to find their place in the market. If we think of a startup ecosystem as a product development pipeline, its role is to guide startups through this process—helping them validate ideas, develop sustainable business models, iterate, and scale.

In his research, economist Paul Romer has highlighted that innovation and knowledge spillovers are critical to economic growth, particularly in regions aiming to foster entrepreneurial ecosystems. Romer’s “endogenous growth theory” suggests that the creation of new ideas (i.e., new startups) spurs economic development when properly nurtured. This brings into focus the role of the ecosystem: like a product development framework, it should be designed to support iteration, knowledge-sharing, and long-term growth rather than short-term, flashy successes.

What’s Essential in Product Development?

In the context of startup ecosystems, there are a few core components that are essential to this development process:

- Market Validation: Just like any product needs to be tested in the market, startups require real-world validation that there is demand for what they are building. This is a fundamental necessity that often gets lost in flashy accelerator programs or initiatives that focus more on visibility than actual market traction. Notice, I did not say “customer” validation as it is increasingly evident that the idea of customer validation is misleading founders to suffer from confirmation bias while neglecting the critical path of market research and competitive analysis.

- Iterative Development and Feedback Loops: Just as product designers must continuously iterate based on user feedback, startups need environments that emphasize building, testing, and refining based on real feedback. Unfortunately, many ecosystems focus more on “pitching” and less on real, tactical development.

- Access to Resources (Capital, Talent, Networks): Startups, like any product, require resources to move from ideation to scale. This includes capital (to grow), talent (to execute), and networks (to connect with customers, investors, and partners). An ecosystem should be judged on its ability to provide meaningful access to these resources; I’ve covered meaningful access before because unfortunately it means what most ecosystems won’t do (and what most cities and programs can’t or don’t know how to do): removing the good-intentioned participants that don’t know what they are doing or are trying to monetize founders.

What’s Unnecessary but Over-promoted?

Many startup ecosystems fall into the trap of promoting unnecessary elements that do little to foster real product (startup) development:

- Pitch Competitions and “Demo Days”: While these can be helpful in some contexts, many ecosystems overemphasize pitching over product development. In a product development cycle, a prototype isn’t endlessly pitched; it’s tested. Similarly, founders should spend more time refining their startups with real customer data, not tailoring pitch decks for competitions.

- Over-glorification of Office Space and Coworking: While having a space to work can be useful, ecosystems often place undue emphasis on physical spaces as a sign of development. Great products are created in garages and bedrooms long before fancy office spaces become necessary. Startups need lean, resourceful environments, not cushy office perks.

- Networking for Networking’s Sake: Ecosystems often promote networking events, without necessarily creating environments where useful, action-oriented connections can be made. For product development, what matters more are strategic relationships that lead to partnerships, investments, or key hires—not sheer volume of connections.

Notably, many of us are increasingly appreciating that if founders are struggling to connect with people, that they need introductions to investors, or that they spend recurring time at a hub out of a desire to network, something cultural, economic, programmatic, or systemic must be wrong.

What’s Involved in Product Development—and What’s Distracting Founders

In product development, focus is everything. Successful products are built through a process of iteration: rapid prototyping, testing with real users, collecting feedback, and making necessary adjustments. In the world of startups, this is no different. As Steve Blank, creator of the Lean Startup methodology, states: “The key to a successful startup is not just to build a product but to build the right product.” This process—often referred to as “iterative development”—is how startups eventually find product-market fit. Yet many ecosystems inadvertently distract founders from this critical process by emphasizing activities or practices that don’t serve the core development of the product itself.

One such distraction is the overemphasis on media attention on the ecosystem itself, rather than the startups, and early-stage pitching at networking events (frankly, usually to pretend for sponsors or investors that the venue/hub is capable of providing deal flow to people who aren’t effectively getting it otherwise – doesn’t that signal something is wrong?). While pitching is a necessary part of startup life, as it allows for validation of ideas and storytelling, ecosystems often glorify the pitch itself rather than the validation and iteration that should follow. “Pitch competitions, while valuable for visibility, often push founders into a performance mindset instead of a problem-solving mindset,” notes Josh Lerner, an economics professor at Harvard Business School who studies entrepreneurship and innovation.

Now, I’ve covered how to pitch effectively, many times over the years, but every time I note that it is because the order in which, the content, and the quality of communication, tell us a lot about the psychology and priorities of a founder – that though, startups winning because of a good idea and well delivered pitch are distracting us from seeing if the founders are actually capable.

Runway and Financial Stability

The biggest challenge to effective product development for startups is often a lack of financial runway. A study by the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation revealed that 82% businesses fail due to cash flow problems, a figure that highlights the importance of sustainable, long-term funding in startup ecosystems – but more importantly notice, running out of cash is NOT the cause of a failure when we’re dealing with startups that start without it: it’s a symptom of something else. Founders misled by the ecosystem or investors, to chase customers or meet the expectations of bad advice from investors dangling checks, end up forced into survival mode, making short-term decisions rather than focusing on iterative product development – because they were erroneously pushed into the wrong focus. When ecosystems prioritize rapid scaling or glamorize “hustle” without providing the capital necessary to sustain real growth, founders are pushed to seek investment prematurely, often before they’ve validated their market.

Furthermore, entrepreneurial ecosystems that focus on vanity metrics—such as user signups, social media followers, or media mentions—push founders to chase superficial numbers rather than deeper product-market fit. In a study of 200 startups, CB Insights found that 42% of failed startups attributed their downfall to “no market need,” highlighting the danger of focusing on buzz instead of prioritizing the marketing to determine that there is no market need.

Cultural Barriers: Perfectionism and the Fear of Failure

Ecosystems that promote perfectionism can stifle startups from taking the necessary risks that lead to success. Michael Porter, a leading authority on competitive strategy, points out that “the essence of strategy is choosing what not to do.” In a startup context, founders must be empowered to focus on their core product, make decisions quickly, and avoid the paralysis of trying to perfect every aspect of their business before launch. However, in ecosystems where failure is stigmatized, founders are often pressured to launch something flawless, leading to delayed entry into the market and missed opportunities for real-world feedback. In contrast, ecosystems that celebrate iterative development and embrace failure tend to foster more resilient, adaptable startups. “Innovation ecosystems that tolerate failure produce more innovative outcomes because they allow for experimentation and learning,” once noted entrepreneurship professor Saras Sarasvathy, whose work on “effectuation” argues that entrepreneurs thrive by learning from what doesn’t work.

The Role of Venture Capital as the “Customer”

If startups are products, then venture capitalists (VCs) can be perceived as customers because it’s the investor class that is considering capital allocation in exchange for value into what they venture is BEFORE serving consumers of the solution.

The question becomes: is the local ecosystem producing startups that venture capitalists find valuable?

One way to assess this is by looking at where the money is coming from. If local investors are backing local startups, that’s a strong signal that the ecosystem is effectively supporting the kinds of companies that investors want to buy into.

In his analysis of venture capital’s role in regional innovation, economics professor Donald Siegel has pointed out that venture capital serves as a “signal” of the health of an ecosystem. When local VCs are investing in local startups, it suggests that the companies being built are aligned with market demand. However, when local capital is scarce and investment flows primarily from outside the region, it raises the question: why aren’t local investors stepping up? Often, it’s because the local ecosystem is focused on creating startups that look good on paper—ones that attract media attention or win pitch competitions—but don’t necessarily solve pressing problems or present clear paths to profitability.

Let’s look at Austin, Texas, as an example. For years, Austin’s ecosystem has been touted as a rapidly growing tech hub. Yet, if we take a closer look at localized VC investment trends over the last decade, there’s a noticeable discrepancy between the hype and actual capital inflows. Despite a high volume of startup activity, a significant proportion of venture funding in Austin still comes from out-of-state investors, particularly from the Bay Area. This indicates that while Austin’s ecosystem has produced a high volume of startups (products), many of those products do not match the needs or desires of local capital.

In other words, the local investor base may not see the value in the startups being developed locally, or the startups are not aligned with the particular sectors or growth models that local VCs prefer. This misalignment could be the result of over-promoted aspects of the ecosystem (like pitch competitions or coworking spaces) that do little to drive real product-market fit, which is what VC investors ultimately care about.

In contrast, regions like San Francisco and New York have strong local VC support because the startups developed there are in sync with the investment theses of local venture funds. These ecosystems emphasize product-market fit, iteration, and scalability—just as a strong product development process would—rather than superficial metrics like participation in networking events or media hype.

Developing a Region’s Startup-Market Fit

Provide the startups that satisfy a strong demand within a well-defined target market, which creates a sustainable foundation for growth, and customers (investors) will come. How?

- Understanding and Defining who Values the Solutions

This part is all about deep market research. You’re looking to understand not just demographics but the psychographics, pain points, behaviors, and needs the market. Pinpointing specific personas or segments to target, figuring out the circumstances or challenges they’re trying to resolve, and understanding competition, are critical early steps. - Problem Validation

Once you understand the market, you need to validate that the opportunities are real, pressing, and not just a minor inconvenience. Opportunity > Problem so we validate that a problem exists because there is an opportunity, by engaging directly with potential, conducting interviews, or using market research to help assess whether the problem resonates widely and is compelling enough to demand a solution. - Solution Development and Testing

Here, you’re crafting startups that fit the problems and in which people will invest (whether investors or customers). Prototyping, beta testing, and gathering feedback from a small cohort of initial adopters are important for assessing if a startup effectively solves the problem – and they need funding and experienced resources to do this BEFORE going after paying customers with their solution. Often, this phase will involve refining, iterating, and adapting based on real-world usage and feedback. - Unique Value Proposition (UVP) and Differentiation

For any startup to gain traction, it needs to stand out in the market. Identifying what makes your startups uniquely valuable to the market — in a way that competing solutions do not — is essential. Cities fail this while most startup programs and investors have no idea how to do so. It’s also critical that this UVP is both easy to communicate and resonates with everyone. - Go-to-Market Strategy and Distribution Channels

Startup-market fit also depends on how well your ecosystem helps founders reach and acquire audiences. Understanding the best distribution channels and crafting an effective go-to-market strategy are crucial; your region can do this for startups just as much as your investors are demanding founders do it themselves. - Testing Metrics and Validation Through Traction

Startup-market fit should be measurable and as we’ve explored here, it can be – are investors arriving and funding the products (startups) being brought to market? Traditional marketing metrics such as customer retention, engagement rates, Net Promoter Score (NPS), and revenue growth can be translated to the macroeconomic impact of startups but note that these are trailing metrics, not leading metrics!

Aligning Ecosystems with Product Development

In the end, the success of a startup ecosystem should be measured not by the number of companies launched or the amount of media attention generated but by whether it is creating valuable, investable products. Ecosystems need to stop focusing on distractions like vanity metrics, excessive perfectionism, or superficial pitching and start giving founders the runway and the cultural support they need to iterate, fail, and eventually succeed. As the data shows, ecosystems that emphasize sustainable product development, rather than quick wins, are more likely to create long-term economic growth. And venture capital—both its presence and its absence—serves as a clear signal of whether the ecosystem is on the right track.

If we are to take startups seriously as the experimental products that they are, then local ecosystems must support founders in the same way we support product developers. You can’t just reboot the machine and hope it works when it’s evident something is wrong.

It’s about fixing that bug so as to build something that works, something worth investing in, not just what looks like a healthy ecosystem. Localized VC trends are a clear indication of whether ecosystems are aligned with investor demand. And as venture capitalists continue to serve as the ultimate customer in the startup economy, ecosystems must ensure they are building products that their customer is willing to buy.

I started covering Houston’s startup scene on video around 2013, and what you said about demo days, coworking spots, and pitch events is very accurate. I remember posting about a local startup going public in a Facebook startup group. I couldn’t believe some people got upset about my post. It seemed they were only interested in events and didn’t care about real progress. It’s all good because I cashed in my shares. Here is the startup. https://localsiknow.com/business/indoor-harvest-starts-farming-tech-in-houston

Glad I could help with the data. A question you ask is one I have been obsessing about forever.

In a thriving or superstar ecosystem how much capital comes locally & how much outside?

I am going to give a counter example to your money from the outside driving. San Diego. Forever San Diego has had an underdeveloped VC/investor, but quite successful startup track.

I have been looking for a data source that can accurately (or a least strong point in the direction) for ecosystems what the ratio of local vs outside capital is. Then have a real discussion on what’s the optimal amount, since I know the two extremes are both bad.

Jason Scharf a hypothesis? San Diego has a focused region with specific industries doing well within that focus, similar to Raleigh-Durham. That’s a contributing factor that makes it a bit distinct from most places.

Your question, “In a thriving or superstar ecosystem how much capital comes locally & how much outside?” might answer that with a detailed study of investment by sector (and I’m going to be diligent in saying, that can’t mean Enterprise, SaaS, or the other generic terms I frequently get uppity about). I’m curious too…

Let’s pick somewhere else to play out my thesis and your question

If Detroit was still the dominant hub of the auto industry, it stands to reason that local investment might be light while outside investment is disproportionately high. Likewise, if St. Louis has a soft startup ecosystem or no clear specialization, VC overall would languish.

Dexter Bayack cheers. It’s very accurate almost everywhere in the world. I’m finding that the underlying cause of most of what happens in startup ecosystems is actually that they don’t know what to do. I’ve started looking at the need for events, referrals, demo days, etc. to be more of a reflection of a problem, than a healthy ecosystem.

Consider, if founders and investors knew what they were doing, they wouldn’t need all that.

The problem is Boston is also hyper focused and has a thriving VC scene. San Diego also does 2-3x what RTP.

I think there is something to find in this data, but need to see it first. No one has done this analysis

Jason Scharf per capita / relative to time

Boston is a much older startup ecosystem than San Diego… more runway for investor ROI cycles

This kind of study only works by sector, per capita, delta over time.

Another example, Austin has been at it as long as Silicon Valley – yet, it didn’t really boom until 2008 or so. Austin certainly has more startups per capita. Why?

One might consider today’s notion of “startup ecosystems” to be fatally flawed. Traditionally, folks start businesses because they think they have something to offer – a solution to a problem, a new & better way of doing things – that they can’t bring to market in other ways. Either the market pulls them into it (Ken Olsen responding to demand for logic boards he was building at – I think it was Lincoln Labs) or Edson DeCastro leaving DEC to build a product that DEC didn’t want to pursue; the same model my Dad used in starting his company. Or an itch that one just has to scratch.

This notion of wanting to start a business, and then searching for a product or service, is just wrongheaded. If what you want, or need to be is in business – then buy a going business, or a franchise, or respond to an RFP in your field of expertise.

Miles Fidelman sure… except you’re talking about existing businesses or starting new businesses. I’m talking about startups.

Which is to say, I agree with you; if you want to start a business, it’s easier to buy an ongoing business, franchise, or respond to an RFP – though still, some need to just start their own because such opportunities don’t exist.

On the other hand, startups always require the founders doing the work to start a venture that might work out as a company. Pray tell, how is a startup ecosystem fatally flawed? It’s impossible to disregard the fact that some places (ecosystems) develop startups better than others.

Absolutely, Paul O’Brien – hit the nail on the head!

Lauren M. Postler right? Now get all the people trying, to wake up

Hm, I wonder if Norris Krueger or Nick Smoot have any thoughts…or publications on this?

Paul O’Brien That’s precisely the point. “Wanting to start a business” is not a particularly good reason to start one. Real entrepreneurs start with a vision, or a mission – and build a business around it – we need ecosystems that help folks pursue those visions & missions – not ones that say “hey, come start a venture and then find a vision or sense of purpose” – that’s just backwards. Yet, all too many current programs encourage just that.

Ah, yep Miles Fidelman, we’re on the same page. I see things encouraging that people should quit their jobs to become entrepreneurs, offering a paid for desk at a coworking space so you can network with mentors… it’s disturbing how much our society allows organizations and individuals to take advantage of people trying to get meaningful help.

Jason / Paul O’Brien Indeed. And it’s built mostly around MIT – as a source of technology, and folks ready to commercialize it. (Note, I was there – helped start the MIT Enterprise Forum – where we helped folks, who had already gotten started, pursue their next round of funding.) Based on that experience, and some later projects, it’s become very clear that a successful startup ecosystem needs something to build on – either a source of technology (a university, a national lab), or a target – a source of problems to solve – like a military facility (Rome Labs, the Air Force Research Lab in Dayton), or a city badly in need of redevelopment (lots of entrepreneurial activity sprang up in Detroit in recent years).

I love what you are pointing out. 3 years ago I made a small research on 30 countries speaking with entrepreneurs, accelerators and VCs to discover that the startup ecosystem is imperfect.

That’s what brought me to think that funding should be the natural consequence of a sustainable growth. Instead than the hardest milestone of every startup.

Differently than you, I don’t see the startup ecosystem as investors centered

Ah but dig deeper in my article; I don’t see startup ecosystems as investor centered and in fact even pointed out that what I’m saying does not mean startup should (or only count) if they raise capital. What I’m observing is that investors are a barometer… IF the volume of startups is growing AND the ecosystem is effective THEN venture capital would follow. So, if it doesn’t, A or B is failing to deliver.

Startups today often chase investor expectations rather than authentic, mission-driven impact.

This raises the question: Are we prioritizing the right metrics for sustainable success, or merely reinforcing short-term gains?

Great share, Paul O’Brien??

Cheers Sidney Evans, I think I’ve simplified it into a formula or sorts, because some discussions elsewhere misunderstood me to be claiming raising capital and VCs are most important (that’s not at all what I’m saying).

IF the quantity of startups is growing in the region AND the ecosystem is effective in helping them THEN venture capital would follow. That is, we’d see a relative increase in overall venture capital investment. And, if we don’t, A, B, or C is broken.

Awesome Paul O’Brien

Excellent article! Agree 100%.

Insightful post! Focusing on building sustainable startups rather than just showcasing them is crucial for long-term success.

Incredible insights!

Focusing on true value and sustainability is key to a thriving startup ecosystem.

Let’s drive meaningful change together!

re: Ecosystems must align with investor demand,

But isn’t this a Catch 22? Isn’t there a point of diminishing returns? As in, the startup is too focused on investors and not enough on The Market? Isn’t that part of the current problem? To much of The Startup Industrial Complex and not enough actual serving of The Market?

For example, at the enterprise level, there’s the famous CM Christensen “The Innovator’s Dilemma.” It’s a great theory, but one that I find incomplete, if not wrong. Hear me out…

When we run down all the usual examples (e.g. Kodak, Blockbuster, etc.) they all have one thing in common… they were publicly traded companies. They were legally obligated to serve their shareholders. That’s manifests itself an (unhealthy) obsession with quarterly results. Those companies failed because they were focused on Wall Street and not on Main Street. They didn’t lack the ability to innovate. They lacked the incentive and a vision beyond the next financial results meeting. Netflix? It did not have that same constraint.

Startups overfocused on investors feels like a problem to me. But maybe it’s just me? That’s nothing new ?

Mark Simchock I teach (advise) that founders should think of investors as the high water mark, not a necessity. That, if you can figure out how to build a company that is valuable to investors, the rest is relatively easy (journalists, partners, and customers) – because investors would only be interested if you have built a company that would be interesting to everyone else.

So no, I don’t think there is a catch-22 because I’m not proposing that all startups should seek funding (or need it).

What I’m pointing out is that investment is a barometer though, in any event.

That, IF the volume of startups in a region is growing (see: Austin) AND the ecosystem is efficient (see; San Diego) THEN we can expect that venture capital will follow that to take advantage of it.

So, when C doesn’t happen, we can accurately conclude that A or B (or both) must not be working.

That, you’ll definitely see some uptick in venture funding when that happens, you must. Out of a thousand startups, something more is getting funded (if it’s a good ecosystem and/or the volume is increasing).

“Venture capital trends are a direct signal of a city’s startup-market fit.” – I really like this. The fact that capital has all but fled a bunch of investment stages and has pooled in both very-early and later stage (like a raver 18 year old working the EQ of a sound system, iykyk…) puts a bee in my bonnet.

I think you’re absolutely right, capital has fled early stages, and some of it lingers around very early stage because it’s propped up by a cottage industry of incubators, accelerators, acquisitions, tax-write off schemes, etc…

But also maybe capital has fled because every man and his dog now wants to have a startup, and are seeing it like the new gold rush – which it really, really isn’t. (or maybe it is, if you consider the dying of dysentery in the middle of nowhere aspect)

I’m not sure how thinking exclusively in terms of local ecosystems is helpful, doesn’t this run antithetical to the very idea of a startup? And yes, ofc having resources available is helpful. Maybe it’s my multi-national / multicultural / multi-languages self talking: I can’t help but think in terms of “twinning” ecosystems/networks, and how this might be more helpful. Thinking in terms of networks, not just locally. Hmm.

Carla Viegas-Barber a thread, because I have too much to say about this

Bottom line, I think your theories are entirely correct.

“has pooled in both very-early and later stage”

That’s an entirely accurate observation that I’ve been meaning to write up – and call investors to task for it happening. Because what is happening is three things…

Some investors realize they can pay themselves for starting a fund, small enough, that the 2% cuts them a healthy salary. These investors actually don’t want to collaborate, likely don’t have experience, and have no intention of actually helping startups, they like being a “VC” (in name).

More, investing in startups has become cool. It’s heavily promoted as being sexy, influential, and meaningful (after all, you should help entrepreneurs, right?). This causes as flood of “Angel Investors” (also, in name), and the evidence of that happening is that we’ve had a boom of Angel Groups – which are what? Group think to make investment decisions because they people in them actually can’t, won’t, or don’t want to be known for investing: nothing that one should expect of an actual Angel.

This results in a HIGH volume of seed investment that either/both shouldn’t have received funding OR can’t afford to invest in the mid-stage.

That explains your early stage still getting capital while mid doesn’t. What of later?

Well later stage is still getting a ton of funding for the same reasons, ironically.

Investors don’t know what they’re doing.

So, if you don’t want to invest at the early stage, you go to the later stage because you trust that previous investors made the good decisions.

Family offices, companies, and other larger sources of capital are moving into more of what technically should just be considered Private Equity, but since saying “VC” is still sexy, cool, and fun, they claim to be a VC.

This causes the large pool of late-stage investment unwilling, unable, or uncertain about how to discern any good investment earlier.

Begging the question, WHY?

I believe it’s consistent with the reason most startups can’t make it work, why most small businesses struggle, and inexplicable to some, we have the influencers making a fortune starting their own thing on TikTok…

The internet broke everything. Largely, only people in Silicon Valley really understood how, and so for decades, it dominated because it understood, first-hand, the implications. More or less no one anywhere else had that experience.

And that experience takes decades to emerge because…

1. Marketers get it. But at this point, everyone who else who doesn’t got burned by bad marketers, or focused on sales without marketing, and failed.

2. In time, engineers catch up, as we’re now seeing in places like Austin. The challenge there is the engineers aren’t working on how the internet works, they’re working on solutions and opportunities because it isn’t perfect. This pushes everything online, with either great or questionable marketing – causing further divide.

3. Investors never learn first-hand, because they don’t care. Silicon Valley investors get it because they were in it. Elsewhere struggles because the investors now want to do it themselves because they don’t trust 1 and 2.

Paul O’Brien I have always admired your efforts, as opposed to me watching with knowledge of YC trickery and equity valuation consortium’s, allow FTX to raise more money than all of Texas startups combined.

We’ve been at this for far to long, it’s time we realized that Texas is about to have its own stock market, and maybe we should pay attention and have some respect for people who want to make relative investments scale massively.

The paperwork and math is easy if we want to make ? startups a year through sound respectable investments.

Ajay Desai I have a half dozen conversations a week with people who agree, support, and encourage, but when asked to do, they slip away. I don’t want to say I’ve hardened my approach to Texas and my willingness to have coffee but I’m no longer available to discuss it unless the person says, “here, this is what I am putting in.”

Paul O’Brien funny that when I wrote about later stage investors I very nearly called them PE-adjacent

Will write more tomorrow as it’s late here but now that we found the big gaping hole in the highway – the next question is what do we do about it?

I really want to continue talking, our chat got the cogs turning in my mind – got time for a call this week?

Markets that treat founders like commodities will only attract founders that act like commodities. ? It’s a common misconception that startup ecosystems should be designed to align solely with what investors want. But the truth is, founders are the heart of innovation—bringing the ideas, energy, and risks that drive true change. Instead of shaping ecosystems around investor demands, we should be asking how we can empower founders to create, build, and flourish in ways that are authentic to their vision. When has a big leap forward ever been driven by investor needs alone? Investors often play a crucial role in scaling and supporting, but the original spark—the groundbreaking solutions—come from founders.

Investors frequently follow trends and invest in “proven” concepts rather than taking big risks on groundbreaking ideas. That’s why the real opportunity in today’s startup ecosystems lies in empowering founders with the support, resources, and autonomy to innovate boldly. After all, a healthy ecosystem isn’t about catering to investors’ preferences; it’s about creating the space for founders to realize their full potential, bringing ideas to life that change markets, create movements, and solve meaningful problems.

“Markets that treat founders like commodities will only attract founders that act like commodities.” — BRILLIANT

To be clear, I never said startups should actually align with what investors want; not that only startups that raise capital are valid nor that all startups should. The realization here is simply that IF things are working, venture capital will increase because it will follow the opportunity created by that.

Mark Simchock ideally these should be one and the same – and investors that seek out antithetical metrics etc from startups… aren’t really startup investors at all, or if they’re guiding their investment decisions by that way of thinking – likely they won’t remain startup investors for long: they’ll seek out startups guided by the wrong metrics, invest in them and watch them crater.

So over time – the good ones should remain and what they value and what makes a promising startup are one and the same (basically what Paul said!).

Carla Viegas-Barber re: ” aren’t really startup investors at all, ”

Yes, and this is one of the inspirations for what I call The Startup Industrial Complex. It’s a system that serves itself more than it serves the market. It’s not just investors. There are plenty of founders just playing the game as well.

That aside, ultimately, the market comes first. To your point, smart investors will be attracted to startups with that focus. The less smart investor use a lens where their needs are the priority.

Mark Simchock “startup industrial complex” – had been searching for a term for this, that cottage industry that has sprung up, you nailed it. That’s exactly it.

Carla Viegas-Barber The spinoff industry I get. But it seems to me – because there has been so many tossing so much money around – that it’s become an industry more focused on serving itself and perpetuating itself to a fault. The Startup Industrial Complex is the most successful startup out of all the startups its served.

I’m being over the top, but not by much.

p.s. It’s like all these “thought leaders” that sell how to become like them. When in fact, their number 1 product is selling the idea of becoming like them but not actually doing so. If that makes sense.

Mark Simchock eh… over the top? What is the purpose of the Military Industrial Complex? To perpetuate itself by encouraging others to war. I can’t think of any more apropos description of those local startup hubs, influencers, or events, that encourage everyone can and should.

Some contrarian thoughts… ?

Well, they were contrarian but it seems you may have “iterated” the original post between the time I started this draft and worked back to it… ?

Either way …

1. I agree in most places – even classically “successful” ecosystems – that startups are too often performing vs. thriving.

I think emphasis on venture capital could continue to worsen the problem.

It is hard to “serve two masters” and identifying *investors as customers* even for intermediaries like regional economic development groups, risks prioritizing raising capital over value creation for real businesses (B2B) or consumers.

2. Raising capital is a lagging indicator, even when it is distributed rationally and equitably — which is rarely the case.

*Public customer testimonials* and unequivocal evidence of value creation are the real regional impact indicators and in fact these are leading indicators for rational, equitable venture capital, where it does exist.

3. You often do say “Go talk to customers,” and DO NOT build things no one wants.

I say — double down on this — where is there a regional dashboard of business impacts with any kind of validation metric? Where the businesses and consumers we serve affirm that impact?

I also re-read the article and found a few finer *hopefully actually contrarian* points —

1. Portfolio theory presumes large numbers of startups will fail and preferably fail fast, with founders rapidly pivoting…

So I am mixed on “startup success” rate being a metric because it may hurt the next point (#2) …

Startups as a Science (SaaS) is perhaps what I aspire to see — people running meaningful tests of value creation, not presupposing that it is good or bad for a certain % of hypothesis to be true or untrue.

2. The key difference between the Bay Area and other spaces is insane risk tolerance —

I have written a handful of meaningful Angel checks and while I am at peace with the capital I deployed, the idea of writing 20+ and waiting 7-10 years to see 1 in 20 (maybe) win while 19/20 likely lose is a wild proposition.

But this kind of investment and true “seeding” is a difference maker. If you needed to plant 20+ seeds for a plant to take root and bear fruit ? you could try to improve the ratio through adjustments to the soil and environmental conditions, but writing checks aggressively is the real “nitrogen” in the system.

All that said, I love Austin – and I believe in Texas – and I appreciate everyone who works this garden.

Michael Barnes I’m pondering… because I didn’t rewrite the post… because, I am not saying focus on investors, referring to your point that I’m encouraging emphasis on venture capital… and then I jump to the end of your point just to give you a sense for why I say I’m pondering, and you have #3, “you often do say, “go talk to customers” which is in fact very much so something I never say and severely criticize ? So, I’m a bit confused.

Let me reply anyway…

Your first comment seems to agree with me in general, and what I’m actually saying, but at the same time seems to miss my point. Yes, VC is a lagging indicator, that’s why I made the point about asking how many 7 year cycles should we go through before we start wondering why investors aren’t participating in the hype? Customer testimonials and businesses thriving are absolutely the indicators of regional economic development and so-called “real” businesses … which is why I made a point to distinguish that we’re talking about startups and innovation here, explicitly not businesses that naturally have customers.

Second comment, your first point I agree with entirely, and what I’m pointing out is that in some ecosystems, those founders to rapidly pivot (or fail fast) but notably in Austin, they don’t; the thesis is the focus on customers, which can be a false indicator of innovation and disruption, which is what startups are doing distinct from businesses. When you have some customer adoption and so-called traction, it misleads misled founders from threats, opportunities, real capital requirements, or other indicators, that something is off, but it keeps the founder hanging on (rather than rapidly pivoting) because they have some customer validation that implies they’re right. Point number 2 you make here, is absolutely correct; and somewhat what I’m exploring, that that risk tolerance is a necessity among investors if you are to have an in-fact healthy “startup” (not new business) ecosystem.

Ultimately though the point isn’t investors are customers. That’s an analogy. It’s that if we conceive of startups as products, then the customer of “startups” is investors (because it isn’t the end consumer, they buy whatever it is the startup is trying to provide). Startups, macroeconomically as a product, are bought by investors (who get ownership of those, as such). That, when we consider it that way, then it is very fair and valid to appreciate that startups thriving = venture capital coming into the market to buy startups – not all, no it’s not necessary or a dependency, but investors don’t ignore and miss out on the opportunity to invest, IF / WHERE there are startups worth funding. Hence, if the measure of overall venture capital is *unchanged* in a region, it’s fair to start asking – why?

Oh man… reading this and knowing that almost every single one of my fellow nominees for ecosystem builder of the year listed “access to seed capital” as one of the biggest challenges Houston face tells me we have an market fit problem. Fascinating read Paul O’Brien, now to brainstorm some solutions.

To resonate with investors you need to resonate with customers first. In today’s environment (if there ever was) there is no escaping from the founder pain and financial risk of bootstrapping until PMF is proven. Fortunately, this is also better for the founder(s) in the long run, as early VC, even if available, is a toxic distraction from building a sustainable business that is controlled by management (not investors) and ultimate returns the value created to the people who created it.

Paul O’Brien What’s amiss is the understanding of the term ‘worth funding’. I’ve experienced the different start-up investment cultures in the UK, Silicon Valley, and Texas. ‘Worth funding’ means something different in each location and founders need to adapt to that (or bootstrap of course). Every ambitious city wants to replicate the SV VC culture, but who has done it? Shouldn’t we accept by now that each metropolis is different and SV cut-and-paste doesn’t work. The Houston economy seems to be doing fine (to say nothing of its Michelin stars) so let’s not try to change it but to accelerate it based on its unique strengths.

You’re missing the point Steve Jennis

Yes, worth funding means different things to different people and cultures. And we already know, you and I have a bit of a different opinion on startups and VC, which is fine, good. None of that is relevant in what I’m saying herein.

No place can nor should replicate the SV VC culture – that’s the work I actually do, working with cities on their ecosystem. And no, they shouldn’t replicate.

All that said, the premise here, which is studied and a fact I’m merely illuminating, is simple.

IF “startups” are growing (as is the case in a place like Austin) OR if “startups” (I put it in quotes to signify defining that however you want) are successful there, THEN venture capital (again, however you want to define it) would be increasing in visibility and volume. Investors chase opportunity. Yes, they could be Angels, angel networks, syndicates, grants, venture capital funds, or whatever, doesn’t matter….

Therefore, if capital allocation is NOT increasing, somewhat, then *something* is amiss – as explained in the article… startups are increasing in quantity but not succeeding OR investors aren’t aware OR investors aren’t sophisticated… something is wrong.