This is one of those “I did the math” posts, and it might inspire you, but it could also discourage you so before I let you go on into the depths of discouragement, let me point out that what we’re exploring here is how to avoid failure – that, if the math prove that you’re odds are very slim, take that as direction as to your priority and focus (hint: find the partner with whom you can overcome that).

What prompted this was that I was asked by a founder, “Is it permissible under the law to establish a new startup…”

If you’re here wondering whether you’re allowed to start a startup — whether it’s permissible — the hard truth is that the odds of your success are not just low, they’re abysmal. Not average. Worse than average. And the math isn’t just sobering, it’s an ice bath of entrepreneurial reality.

We’ve all heard that 90% of startups fail. That statistic is now basically startup scripture quoted endlessly in pitch competitions, incubator intros, and every investor meeting ever. But while that’s a catchy average to toss around, averages are misleading. They hide the ugly truth behind a pleasant mathematical veneer: if you’re asking questions like “can I do this?”, the odds are much worse for you than that already horrific number.

Article Highlights

The Math

By the way, I hate math, it’s not in my nature beyond basic calculations, with which I find, ironically, I tend to be above average. Beyond that, I just can’t grasp some of this, but it’s bouncind around in my brain that if 90% if the AVERAGE, what are the exceptions? The failure rate stat comes from credible research. According to data cited by Harvard Business School’s Shikhar Ghosh, as many as 75% of venture-backed startups fail, and the broader ecosystem often pushes that number up to 90%, depending on how you define “failure” (dead, pivoted beyond recognition, acquired for scrap). Forbes, CB Insights, and Failory have all echoed these numbers. It’s not new.

Now, here’s where it gets spicy.

A study from Oxford, co-authored with University of Technology Sydney (UTS) and the University of Melbourne, indicates that only about 8% of people have what can be reliably considered an entrepreneurial personality type. You know the type: relentlessly proactive, risk-tolerant, resourceful, often obsessive, typically allergic to authority – you could say, someone who doesn’t ask if something’s “permissible” before doing it. As The Startup Genome Project puts it, entrepreneurs are “driven by discovery,” not consensus.

What’s more, these entrepreneurial types are not just different; they are statistically more likely to succeed. According to the same body of research, entrepreneurs are 8x more likely to succeed in launching a viable company than those who are not.

The Real Odds and the Unexpected Consquences

If 90% of startups fail, that implies a 10% average success rate. But remember, that’s the blended average: a statistical soup made up of both true entrepreneurs and everyone else who just thought starting a business sounded fun after reading “The Lean Startup” or because the local startup hub said everyone should (with their *paid for* help of course).

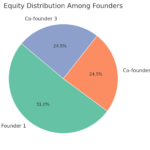

Let’s assume the population of founders looks like this:

- 8% of people are entrepreneurs (we’ll call them Type E)

- 92% are not (Type NE)

- Type E founders are 8 times more likely to succeed than Type NE

So how do we model this?

Let’s denote the average probability of success for Type NE as x. That makes the probability of success for Type E = 8x.

Now, to calculate the overall average success rate:

(0.08 * 8x) + (0.92 * x) = 10%(0.64x + 0.92x) = 10%1.56x = 10%x ? 6.41%

This means:

- Non-entrepreneurial types (92% of people) have about a 6.4% chance of success

- Entrepreneurs (8%) have a whopping 51.3% chance of success

(because 8 × 6.4% = 51.3%)

And that is the limit of what my TI-85 Calculator brain knows how to do (and I’ll even admit that I question if I got that right – so feel free to correct me!)

Let that sink in. The entrepreneurial population has five times the odds of the average, and nearly ten times the odds of someone who isn’t. You’re not just less likely to succeed if you aren’t entrepreneurial. You’re practically doomed unless you find someone who is.

Put aside whether my math is correct, Martin O’Leary, whom I’ve come to love given his work through Uncharted, shared the other day, “In startups, you ask forgiveness. In big orgs, you schedule a meeting to discuss who might give permission… next quarter.” Ask yourself the question to which we all know the answer, which organization drives innovation?

What This Means for You, the Hesitant Founder

If you’re here asking if it’s okay to start something, the answer isn’t about legality. Unless you’re living under an authoritarian regime where business creation literally requires permission slips (and if that’s the case, you’ve got bigger issues), asking if you’re “allowed” reveals something deeper: you’re probably not wired for this.

Entrepreneurial people don’t pause at the door waiting for permission. They break the damn door down, replace it with a better one, and then charge admission. They move fast, test fast, fail fast, iterate faster. They don’t wait for the world to validate them, they validate themselves through action.

Seeking approval, reassurance, or external validation, signals that you’re not likely in the 8%. That’s not a sin. It just means you need to partner with someone who is.

As Steve Blank, the father of modern startup methodology, puts it:

A startup is not a smaller version of a big company. It’s a temporary organization in search of a repeatable, scalable business model.

And you don’t search by sitting around asking if you’re allowed to explore.

Oh! The actual consequence of realizing all this, is actually not the potential discouragement that you are more likely to fail, and it’s not praise and celebration of entrepreneurial people being, in some way, better. Being an entrepreneurial person comes at great cost, with such people suffering from estrangement from society, incessant objection, their work being questioned, being difficult to work with, and usually struggling financially. If you’re sitting there asking how you become an entrepreneur, stop! What you want to be asking of yourself is your strengths and weaknesses and overcoming those by working with people who complement you.

Start Asking Who Should with You

You don’t get to build a successful company through wishful thinking or by following someone else’s checklist. You are NOT going to be successful because some customers say so and affirm an opportunity. You need conviction, obsession, and the kind of unreasonable belief in a better way that makes other people uncomfortable. That’s what it takes. If that’s not you? That’s fine. That’s what co-founders are for.

The harshest irony is that the people most likely to succeed in startups are the ones least likely to ask questions like “can I?” They just do. Because their brains are wired not to tolerate mediocrity. Because they don’t respect barriers that only exist in imagination, or even in laws. Because they look at the status quo and say, “this is broken, and I’m going to fix it, even if society says I can’t.”

Statistically? If you ask, your odds of success are about 6.4%. Obviously, hopefully, you want to be working with the person for whom those odds are around 50%.

Start by being brutally honest with yourself about what you bring to the table. Are you the entrepreneur? Or do you need to find one?

Challenge yourself to understand why validation is something you do, not something you get.

very insightful.

The 8% stat is powerful. We love to glamorize entrepreneurship, but the it’s more a neurological and behavioral anomaly. It’s not some job title you apply for. Great founders aren’t shaped by consensus they’re driven by compulsion.

And thanks for the shoutout!

Indeed.

One starts a company because it’s the most effective way to pursue an interest or goal. An itch one NEEDS to scratch. The same reason someone enters the military, or priesthood, or martial arts. It’s why Edson DeCastro started Data General, when DEC went with the PDP-11 design rather than the Nova. (And why my Dad left a defense firm to start building interference measurement gear for NASA).

Generally, it requires a team. Even if you’re an artist, or musician, or actor, or writer – you need people around you … sponsors, patrons, cast & crew, editors, illustrators – nobody can do it all.

Narcissism & Dunning-Kruger syndrome are good contra-indicators. The ability to persist, until everything that can go wrong, has gone wrong – and keep going forward – is a requirement.

The Japanese have the concept of Ikagi. Frost wrote, “Only where love and need are one,

And the work is play for mortal stakes

Is the deed ever truly done

For Heaven and the future’s sakes”

(Oft quoted by Robert B. Parker in the Spenser books, and the source of the title for “Mortal Stakes” – the 3rd in the series.)

And even then, after pledging one’s life, fortune, and sacred honor, the best that you can hope for

Is to die in your sleep.

Miles Fidelman Damn fine comment.

Jeffrey L Minch Aww shucks. 🙂

Great hypothetical Paul. You’re right that the right team can be a gamechanger for teams in challenging situations where the odds are stacked against you.

You can see this in Canva. Prior to onboarding Cameron Adams, the company as the third founder they struggled but after that it skyrocketed.

Another iconic example is The Beatles. When Ringo Starr joined, the band’s dynamics transformed.

Paul X McCarthy dammit you’re going to bring up The Beatles! Now I’m going to have to write about them

p.s. I want to add – again? – that I LOVE this definition of a startup.

Far too often – even on LinkedIn -0 ppl say “startup” – because it’s trendy to say so? – when they really mean “new business” or “new company.” Starting a new business doesn’t mean you’re starting a startup. I wish that myth would roll over and die already

“A startup is not a smaller version of a big company. It’s a temporary organization in search of a repeatable, scalable business model.”

Mark Simchock that definition is all Steve Blank, and it’s absolutely perfect

“Because their brains are wired not to tolerate mediocrity”

I think the partnering with one part is understated in the ecosystem. There is too much emphasis on pairing archetype skillsets (one creative/right + one technical/left ).

What does the non-entrepreneur archetype offer? Maybe the curiosity, sanity check, calculated caution and slow down to cut the obsessive cycle time.

Fatin Kwasny what does the non-entrepreneur type offer? I’m going to start digging into that research, I want to go from failed founders to founding teams, to figure out if the wrong person on the team is the contributing factor (I suspect so)

Preach!

CS Freeland we need more ministers of startups

You take a very rational approach to the math of entrepreneurship. The challenge is that that is historic.

History is what we know after we make a lot of mistakes.

Very few first time entrepreneurs actually think they can fail. Part of being an entrepreneur is not takikng counsel of one’s fears. Maybe not being reflective enough to even catalog one’s fears.

The first company I ever started was based on my returning home from 3 absolutely delightful months in the south of France and thinking, “Hmmm, I wonder what I should do next?”

One conversation later, a partner and I had started the first of what would be a handful of companies.

There is something to be said for ignorance.

The payoff for being a successful entrepreneur is not just financial. It enriches our ego and nourishs our self-esteem. Those are big currencies. Nobody likes to talk about that, but it does.

Cheers.

JLM

great analysis and a killer point, I don’t think the model is very close but the conclusion is right on- too many people/teams are encouraged for self serving reasons by the startup industry. Most are not real candidates to manage themselves and many more might grow a small/medium size business, which is a fine thing, but a whole different animal from a “startup”.

Ron Clark Never assert that you’re right, but when you can start a conversation or spark the discussion, you’re on the right track. And making a difference for people.

Thank you for your praise and perspective,

re: The entrepreneurial population has five times the odds of the average, and nearly ten times the odds of someone who isn’t.

This is certainly interesting. I wonder if it’s the difference in the ideas each group generates. The difference in execution. Or some combo of both? Or some other characteristic unique to each.

I’d also be interested in seeing some details. For example, let’s say the “average success” takes (e.g.) three years and along that timeline there’s a often a key turning point at (e.g.) two years. But maybe most “start up” failures toss in the towel at two years?

I agree. There’s certainly personality profiles that are better fit than others. But I’m wondering – aloud – if given some data some of that can be mitigated if expectations are better set upfront, a/o along the way.

100%

If this marketplace ever made you feel like you didn’t belong; just know you’re not broken. You’re building something real.

Founders on a deeply personal mission aren’t looking for someone to redirect or “optimize” them. We don’t need control; we need support to execute.

The whole collection of founder support model playbooks? They’re upside down. And they have to flip.

Because access to execution is access to equity. And too many brilliant, wired-for-impact minds are still being left out for the performers that will be agreeable, settle, concede their own experience and vision, and of course fail. It’s all so dang ironic; sometimes I. just. can’t.

As Mark Twain once said “There are Lies, Damn Lies, and Statistics.”

I think there is a fatal flaw in the probability calculation (if I understood it correctly): It assumes that entrepreneurs are drawn from the ENTIRE population proportionally:

Which is clearly not true – 92% of startup founders are *not* type NE – because those people self-select a low risk, steady job.

Rather we should assume that 90%+ of startup founders are Type “E” and 90% of startups STILL FAIL.

This suggests that even if you are well-suited psychologically for the rigors of a startup (ambiguity, high risk, etc) – THERE ARE OTHER FACTORS that determine success besides personality type.

Ironically, as a group, women are much more likely to be risk averse Type NE, than the typical male founder. AND on average they are MUCH MORE SUCCESSFUL. So it seems that being more risk averse leads to BETTER outcomes. This supports the theory of a 3rd undefined factor that is primarily responsible for determining success or failure.

And we think we know what it is.

Chris Sorensen define startup for me.

Just so we’re on the same page before considering it further.

Oxford studied 22,000 founders. So sure, while not necessarily representative, that’s a sufficiently large sample size that led them to publish.

I think it’s a bit gender blind. Women often ask different questions and might show more self criticism, self doubt or even ask “for permission” – but in the end they are also often resilient, cash efficient and many more things that makes them good entrepreneurs

I think you’re right Ida, and I’ve seen some great discussion of that difference.

What I find helps us, and what we need more of, is that rather than saying everyone can, we be realistic, like my goal here, and say, “I am… And therefore…”

Everyone “can” but when the goal is success, or more accurately, avoiding the valley of death, we can only help one another by being pragmatic about circumstances and working to overcome them together.

I’d add… Men tend to over promise, which is misleading. That’s not good either, though on the other hand, it’s those lofty promises that motivate support.

Thank you for this piece.

Anyone can do it with enough grit!

My weakness is failure = does not take risk

Absolutely right on. But it’s not 8% (those are folks who are “entrepreneurial”). It’s 1% (natural born entrepreneurs) + 4% (the half of the entrepreneurial folks who actually break through their comfort zone and Just Do It).

I really appreciate your writing in this area, Paul O’Brien. Totally agree that it’s a mentality thing. There’s this entire industry built around the idea that anyone can be taught to be a successful founder, when the reality is much harder to accept (though I do think resilience and grit can grow stronger with practice).

I’ve seen brilliant, capable people destroy their mental health and finances chasing something they weren’t temperamentally suited for. And I’ve seen people with mediocre skills but the right psychological makeup succeed against all odds.

The traits that let you sleep at night when everything’s falling apart aren’t teachable in a weekend workshop. But we keep pretending they are because the alternative is uncomfortable.