He was no wizard. Magic is the soft word we use when we can’t explain how someone bends the laws of reality. Willy Wonka bent them with sugar, steel, and science. His factory wasn’t a place of spells, it was a cathedral of chemistry, a machine that turned the imagination of children into industrial-scale production. He wasn’t born rich. The money came from work, obsessive, unrelenting work. From an engineer’s mind and an artist’s hunger, he built a world from cocoa beans and a dream that soured. Betrayed by Slugworth, the archetypal industrial spy (so it seems), Wonka did what so many brilliant founders eventually do: he lost faith in the world and shut the gates.

If there was magic, it wasn’t in his candy. It was in his control. Over his formulas, his workforce, his factory, and his vision. He was a maker. A capitalist genius. Damaged, yes, but in that damage, a reflection of the founders who would follow decades after being inspired as children in front of the television.

Article Highlights

The Industrialist Behind the Illusion

To understand why the startup boom of the early 2000s felt so familiar, you have to remember that those entrepreneurs grew up in the 1970s and 80s. We didn’t worship venture capitalists or MBAs. We grew up with Doc Brown’s time machine, two nerdy teenage boys who create a perfect woman using a computer and a doll, a Real Genius, The Manhattan Project, an Inner Space, and a team of friends that invent proton packs. Our patron saint of invention was Gene Wilder in a purple coat, walking out of his factory on a cane, pretending to be frail before somersaulting to his feet. That scene, famously demanded by Wilder against the director’s objections, set the tone for everything that followed. He told them, “From that time on, no one will know if I’m lying or telling the truth.” That’s entrepreneurship in a sentence. The founder’s paradox: the reality distortion field. The limping magician who suddenly cartwheels into control. Every successful founder pitches that way: feigning humility, promising wonder, concealing the mad precision underneath.

Wonka was the perfect entrepreneur long before we had a word for “startup.” He built a vertically integrated supply chain from jungle to packaging line. He imported labor through global arbitrage; paying the Oompa-Loompas in cocoa beans, their chosen currency, rather than dollars. It sounds scandalous until you realize it’s the same logic that built modern manufacturing: offer safety, dignity, and abundance to those escaping worse conditions, and they’ll build empires with you. He wasn’t exploiting them, he was protecting them, giving them purpose and prosperity inside a closed ecosystem (let’s not get into the actual history of the story found in the book; that misses the point I’m making here). Ask anyone who’s run a startup in stealth: sometimes the only way to innovate is to seal the doors and control every variable.

Gene Wilder’s Determination and Creativity: The Founder’s First Pitch

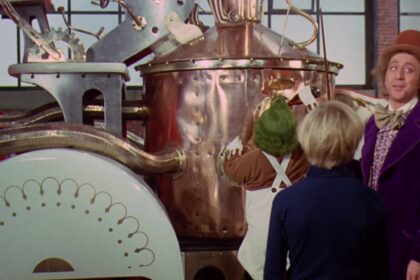

Wonka controlled everything. That was his genius and his flaw. His world was a symphony of mechanical precision: chocolate rivers, lickable wallpaper, Everlasting Gobstoppers. Each product was a proof-of-concept that bridged physics and psychology. His confections weren’t magic tricks; they were feats of engineering.

And yet, at the earliest stages of his innovation, he taught us why so many founders fail now when they build an MVP without doing the market research: The Three-Course Dinner Chewing Gum was food science gone rogue. Fizzy Lifting Drinks were the aerospace industry in a bottle but with a dangerous implication. The Television Chocolate Room was early-stage quantum teleportation wrapped in an irreversible joke.

He warped reality not with spells but with equations and where it worked, he changed the world, but because he only let the customers in the workshop when he felt he was ready, he also had a lot of experiments gone wrong. Machines, chemicals, and willpower make science indistinguishable from magic, the heart of a startup, teaching us it’s possible to invent a better world, and yet the movie also set the stage that if you disregard the market (as so many of you do these days, until you want to let people in), you’re more likely to cause harm.

Every detail of his operation anticipated the startup ethos. His factory was the prototype of Apple’s design lab, SpaceX’s hangar, and Google’s X division rolled into one. Every room was a skunkworks project. Every Oompa-Loompa chant was a company manifesto about the consequences of bad user behavior. When Augustus Gloop fell into the chocolate river, it was a product demo gone wrong. When Violet Beauregarde inflated into a blueberry, it was a failed beta test. When Mike Teevee disassembled himself to reach the television world, it was VR before its time; cautionary tales about overusing technology before safety testing. The entire film is a parable about innovation without marketing, curiosity without caution, and the founder’s moral responsibility for what they create.

The Marketing of Wonder

Wonka was a capitalist Prometheus, stealing the fire of industrial chemistry to create joy instead of power. He sold not necessity but novelty. His customers weren’t hungry, they were bored. He understood the real business model of the modern age: we don’t buy to live; we buy to feel alive. He turned candy into experience, just as the startup generation turned software into lifestyle. The chocolate river wasn’t food manufacturing; it was content marketing. It existed to be remembered, to inspire awe, to turn children into evangelists. Long before brand loyalty had a name, Wonka built the most powerful kind of marketing there is: myth.

And the myth worked. Even his collapse was instructional. Like any founder in a frothy market, he was burned by betrayal. Slugworth stole his IP, just as Netscape was crushed by Microsoft, just as countless dot-com startups were cloned by giants with more capital. Wonka’s response, to close his gates and go underground, foreshadowed the first startup crash. He fired everyone and automated his plant, relying entirely on what he could trust: his machines. His code. His hands. When human loyalty failed, he turned to systems. The 2000s founder did the same with servers, networks, and codebases. Both knew that the only way to eliminate betrayal was to replace people with precision.

But the film isn’t cynical. That’s the genius of Gene Wilder’s performance. Beneath the control and the madness, there’s tenderness; a desire to find one person pure enough to inherit it all. The golden tickets weren’t marketing gimmicks; they were due diligence. Wonka was running a succession plan. The interviews weren’t on Zoom… they were death traps disguised as delights, stress tests of moral fiber, he used his flawed MVPs not to find customers but to find his co-founder. The children who failed weren’t punished by magic; they were eliminated by consequence. Greed, vanity, and gluttony don’t scale. Only curiosity, gratitude, and integrity do. Charlie Bucket wasn’t rewarded for innocence; he was rewarded for restraint. When he returned the stolen Fizzy Lifting Drink, he passed the founder’s test: can you wield power without losing your soul?

When Wonka finally turns to Charlie and says, “Don’t forget what happened to the man who suddenly got everything he wanted,” he’s speaking to every entrepreneur who ever raised a Series A. The lesson isn’t about greed; we learned about gravity. The higher you climb, the harder reality will pull you back. Founders who forget that are doomed to end up like Violet, forever inflated by their own hype.

So, when the kids of the 70s and 80s grew up and started companies around 2000, they were channeling the same energy they saw in that factory: audacity, control, and wonder. The Internet was their chocolate river. Venture capital was their golden ticket. Their startups promised to warp the world, not with magic, but with code. They built social networks instead of candy machines, apps instead of Everlasting Gobstoppers. They made mistakes, exploded a few bubbles, and sang a few moral lessons along the way. But the spirit of it (the manic blend of genius, risk, and ethics) was pure Wonka. Which is my point in observing the film of 1971 – that it BOTH inspired and taught us the critical role of storytelling, teams, and feedback: causing the boom of success among the generation that grew up with those lessons.

To those of us who grew up wanting a better life for Mr. Bucket, Mrs. Bucket, Grandpa Joe, Grandma Josephine, Grandpa George, and Grandma Georgina, Wonka and Charlie taught us a factory is an incubator that inspires and tests, there are risks in launching without marketing, that every pitch deck is his song, and that a soft launch is a set of golden tickets that validate possibilities. The founder’s office, with its whiteboards and prototypes, is where ideas bubble and explode and turn blue before they’re ready for market – prototypes, not MVPs, which need to be put in Bill Candyman’s store.

We romanticized possibilities, people, and spaces, for the same reason children romanticized Wonka’s world: because inside them, we glimpse the fusion of science and story, discipline, and dream.

The Real Magic of Making Things

Willy Wonka didn’t cast spells. He engineered delight. He didn’t perform miracles. He manufactured them. He was the archetype of the modern maker: half artist, half capitalist, wholly obsessed. And he left behind a lesson the startup generation can’t afford to forget: the real magic isn’t in what you make; it’s in how much control you can bear to lose when it finally works.

That’s why, twenty years later, the kids who grew up with Gene Wilder became the entrepreneurs who built our modern world. They saw that the wildest dreams weren’t fantasy, they were prototypes. That science could feel like sorcery if you worked hard enough. That a factory could be a laboratory of joy. And that the song matters as much or more than the science.

And if you listen closely, under the hum of every server farm and the buzz of every accelerator, you can still hear the faint rhythm of an Oompa-Loompa song: a warning and a promise that creation always comes with a cost. But to those of us who watched Wonka walk out on that cane, stumble, and somersault into glory, it was worth it. Because he showed us what the world looks like when imagination gets to build the machines.

A phenomenal article, and analysis, this is very well done – bravo

Thank you!! That kind of comment Wim is like gold to people like me; I had such a good time exploring and writing about this idea.

Brilliant Paul, I was/am a huge WW fan, the storytelling grabbed me the first experience I had with the books and first movie and never let go, can’t imagine a better choice for Willie’s portrayal than Gene Wilder. Your analysis made it fresh and compelling for me – genius stuff and the context in which you placed it

I love this, Paul! Willy Wonka’s journey is a powerful reminder of the blend between creativity and control in entrepreneurship. His story teaches us that innovation thrives in environments where imagination meets discipline.

As leaders, we can draw inspiration from his ability to engineer delight while navigating challenges. Let’s embrace our own unique paths, fostering resilience and curiosity in our ventures. The magic lies in our commitment to create and inspire!

Adam W. Barney EXACTLY. I saw two lessons it seems today most need to catch up about:

1. Tech != startups. Stop chasing tech and capital if you want to be a startup ecosystem, it’s the creativity and storytelling that matter.

2. We draw inspiration but also an example of the harm caused when risk is taken without other people involved who teach us what NOT to do.

And lesson learned from the blue girl who didn’t listen and overinflated from over consumption…

Lori Wong yes! Perfect example. I’m realizing having finished the article, it’s a little like the Grimm’s Fairy Tales of old vs. the sanitizing of them now. The old were horrific but they taught people the important lessons.

Absolutely!

And sidenote, Paul: the original Gene Wilder Willy Wonka sits in my top four movies, along with Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas, Almost Famous and Mary Poppins. #beatthat

Adam W. Barney updating my torrent queue

re: “And yet, at the earliest stages of his innovation, he taught us why so many founders fail now when they build an MVP without doing the market research:”

I have to push back a bit.

First, “fail” is too strong of a word, or it’s at least incomplete. That is, “fail to find a market” or “fail to find profitability” would be more appropriate. The point being, the product could be ahead of its time a/o the team was marketing-challenged. A year later, in the right hands and the product could be a unicorn.

As for MVP and market research, isn’t that an MVP is, or is supposed to be? The failure comes from over-building the MVP a/o not listening to the market’s feedback close enough.

p.s. As someone who also grew up in that era, NASA and the space program played a significant role as well. Then, imagination’s ceiling was going to the moon and beyond. But today? Today it’s more along the lines of “How can we use dark patterns, hoover up data, and sell people’s privacy to the highest bidder?”

Yeah, I might be old, but objectively speaking, today the ceiling is – sadly – lower. The number of zeros in a bank account will NEVER outnumber the stars in the sky.

Too much looking down. Not enough looking up… Infinity and beyond…

Mark Simchock I thought we covered this, you’re not allowed to push back, I’m right!

Now I will grant you, you’ve added some wonderful nuance that everyone should read and appreciate as also correct but it in no way minimizes that what I put out there is fact and the right answer everyone is seeking.

Seriously, the ceiling is much lower. We’re not struggling with poor mentorship and inexperienced investors as much as we’re struggling with having made more room for mediocrity.

Paul O’Brien brilliant insight young paduwan, son of Larry and Mary.

Fun callback and interpretation. Fun fact – “The Candy Man” (no “Can’ in the proper title) was a #1 hit for Sammy Davis, Jr. the next year in 1972, but he supposedly disliked it and thought it would pull his career down (a bit antithetical to the other fact below).

Other fun facts:

The film was financed by Quaker Oats, who was launching a new line of candy bars, as a promotional tie-in.

Sammy Davis, wanted to play the candy shop owner.

The chocolate river was real, but quickly spoiled and smelled awful by the end of filming.

The more you know…or at least can Google/Chat.

This is one of the most touching articles I’ve ever read on the experience of being a founder. The beauty of creating something from nothing, truly a mythical journey filled with challenges that will hone you into who you need to be to complete the quest.

You’ve captured the heart of it, thank you.

I hope it’s read by most with such care. Being a startup founder is one of the most difficult things someone can choose to do. I see far too many try and fail (driving why I do what I do for a living – too many fail when they shouldn’t). Helpful to everyone would be greater appreciation of the fact that it takes someone as unique as Gene Wilder to find success because the effort required is experience, skill, art, and creativity, all in one person.

This is utterly brilliant. I see a lot of parallels with Wonka and Steve Jobs.

Hah! Love this Paul

Yes! The factory was never just about chocolate but about engineering trust through ownership. It was a silent manual for how startups would later be built.

Sydney Polk now I wish I knew what Jobs thought of the movie