The opportunity isn’t that cities, chambers, and investors don’t support entrepreneurship, it’s that they have the chance to support the right kind in the right way. For decades, we’ve been celebrating every new idea in the same sandbox, mixing storefronts with startups, consultants with creators, and then wondering why only a few hold up when things get challenging.

The truth is, most “startup” events, pitch competitions, and accelerator programs are filled with people who care deeply about helping entrepreneurs, they’re thoughtful, experienced, and exactly the kind of people who make communities work. They’re just playing in the wrong field. These are the How-to people, the mentors, service providers, and leaders who know how to get a business running. And that’s invaluable… for new businesses.

Because a new business is built on knowns. That’s not a limitation; it’s what makes it strong. When you open a restaurant, launch a consulting practice, or start a lawn service, we already know how that works. The path is charted. From legal setup to marketing and finance, the knowledge is there. The job of a new business owner is execution of known ingredients together to create value in a proven way.

The brilliance of How-to programs is that they make this accessible. They empower people to launch confidently, avoid mistakes, and build livelihoods that strengthen local economies.

But when those same playbooks are handed to startups, ventures that live in the world of possibility, not predictability, they misfire. Startups aren’t asking how to do what’s been done. They’re asking what’s possible that hasn’t been done yet.

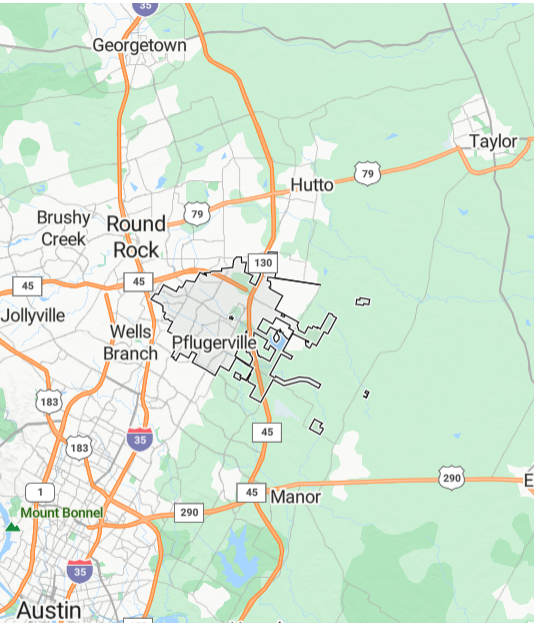

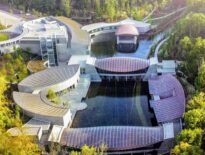

Last week, Texas Venture Fest saw my home busy with events and while my voice wore thing from speaking, among the best was Venture Pfest where Jerry Jones, Jr., Adam Maxon, Lisa Curtis, and Stacy Pfefferkorn, with Pflugerville Community Development Corp., hosted a series of exceptional talks in which what struck me about the room is the crossroads.

Take a look at the map and appreciate how your region of the world reflects the same in many ways; a place ideal to live and work. To the north, Dell in Round Rock, Georgetown booming, and the new Samsung semiconductor plans is in Taylor. Nearby, downtown Austin, or the NW side of the region known for where to find Venture Capital.

Here: corporate, small business, and startup collide.

That’s where the real leverage lies: in rediscovering and realigning the distinction between new businesses and startups, so each gets the kind of support that actually makes them thrive.

Article Highlights

The Difference Between Known and Possible

A new business operates in a world of knowns. You can Google how to start one. There are legal templates, accounting firms, HR systems, and local mentors for every imaginable niche. The variables are predictable. The risk, manageable. These founders need how-to; how to build a financial plan, how to market locally, how to hire their first employee.

A startup, by contrast, lives in the realm of possibility. The model isn’t proven. The market may not exist. The customers don’t yet know they need it. The startup is not a small version of a big company; it’s an experiment searching for a model that works. That’s why Steve Blank’s classic definition still holds: a startup is “a temporary organization designed to search for a repeatable and scalable business model.”

And because of that, startups don’t need how-to. They need experienced-with.

Don’t get me wrong, of course startup founders need to learn how to do much of what has to be done while certainly small business owners benefit from experience. During a talk I joined, with Ashley Ciccel, Sara Hill, and Robert Pieroni, the distinction struck me that small business owners need clarify and focus on how while startup founders need to limit exposure to those that have experience in the sector they’re working.

Startups need investors who’ve lived in the trenches of that sector, advisors who know people and have failed among the many mistakes possible related to what you’re doing, and partners who can guide and even work with innovation. We talk incessantly of startup founders needing to talk to customers and yet a startup might not yet know – more likely, a customer might not yet understand or avoid bias. Where a small business should talk to customers to deliver what they want, a startup is far better off talking to industry experience to explore what might while listening to avoid what won’t.

A new business asks, “How do I do this?”

A startup asks, “Has anyone ever done something like this, and what happened when they tried?”

The distinction sounds subtle, but it changes everything.

Across Every Role: Who You Need Depends on What You’re Building

Advisors

For a new business, good advice looks like process: how to set up a P&L, how to manage operations, how to comply with local codes. For a startup, good advice looks like pattern recognition: what failed in the last ten attempts at this idea, where the regulatory cliffs are, what customers in this market actually buy versus what they say they will.

When a small business asks how to raise venture capital, the answer needs to be, “you don’t.” While a startup asking how to reach customers can’t be misled by an expert in Search Engine Marketing professing that’s what should be done.

Investors

For new businesses, capital comes from lenders or business partners who expect a defined return. The risk is execution. For startups, investors are taking a bet on insight. Venture capital, by design, assumes that most attempts will fail, that one in ten will return the fund. When a founder raising venture capital doesn’t know if they’re building a startup or a new business, the conversation is already misaligned.

Programs and Events

Here’s where most ecosystems fail catastrophically. Local programs are wonderful for new businesses; they create community, peer accountability, and networks of professionals who know how to help you do. But when those same programs brand themselves as “startup accelerators” without connecting founders to experienced-with people in their industry – people who are not likely local – they cripple their participants.

The founder of a FinTech startup in Des Moines doesn’t need a local accountant teaching LLC structure; they need to reach the FinTech founders in Silicon Valley, the bankers in New York, and the funding advisors in Austin who have been there.

This isn’t hard to do, this is freely available to cities in something like Founder Institute’s platform for governments, and yet most places focus locally, at the expense of everyone.

Why Misalignment Wrecks Ecosystems

When new businesses get startup advice, they’re told to “raise a round,” “chase growth,” or read Lean Startup. None of those things make sense for a bakery, a construction company, or a law firm. When startups get new-business advice, they’re told to bootstrap, build revenue early, and take out an SBA loan, usually irrelevant and certainly misleading to the task of validating an entirely new market.

The result? Founders lose time, money, and trust in the very programs meant to help them. Cities pat themselves on the back for “supporting innovation” while inadvertently teaching small-business practices to startups and venture tactics to barbershops.

Alignment matters because the type of advice shapes behavior. Behavioral economist Daniel Kahneman once noted that humans are “loss averse,” we weigh potential losses twice as heavily as equivalent gains. Here, with Gary Bernhard, Ed.D. and Kalman Glantz, Ph.D., when a startup gets new-business coaching, they become too risk-averse whereas when a small business gets startup coaching, they become recklessly speculative. Both outcomes destroy value. This distinction is critical because entrepreneurial founders are unusual optimists whereas small business owners are expecting to make a living, Bernhard and Glantz, “the emotions associated with loss, formed eons ago when loss was always frightening and often damaging to self and others, are with us still.”

The Startup Geography Trap

Economic-development offices love to talk about “local ecosystem building.” It’s a nice slogan, but it betrays the misunderstanding. For a new business, the local ecosystem is the ecosystem. Your customers, suppliers, and mentors are nearby.

For startups, locality is often irrelevant. The ecosystem isn’t geographic; it’s sectoral. A BioTech founder in Kansas City belongs in a global network of BioTech innovators, not just in a local co-working space sponsored by the city. That’s why research from MIT’s Regional Entrepreneurship Acceleration Program (REAP) and the Brookings Institution consistently finds that startup success correlates less with local density and more with access to specialized networks and capital aligned to industry context.

When a “startup program” insists on being local-only, it’s not an ecosystem, it’s a cul-de-sac.

The Civic Cost of Getting Innovation Wrong

Cities and chambers continue to blur the line because they want to check the innovation box. It’s easier to launch a “startup hub” than to design differentiated infrastructure. But the cost of confusion is immense. New businesses and startups create our jobs (far more than attracting companies). Startups, when successful, redefine industries. Each needs different soil.

Misalignment wastes taxpayer money, frustrates founders, and leaves investors disillusioned. It creates a narrative that “startups fail,” when in reality, they were never startups to begin with, just new businesses handed the wrong map.

Fixing Economic Development for Both

The solution isn’t complex, but it demands humility.

- Label things honestly. Chambers of commerce and SBDCs should own the how-to space. Incubators, venture builders, and globally connected accelerators should own the experienced-with space.

- Bridge, don’t blend. Create clear hand-offs: as a new business stabilizes, guide it toward innovation programs only when it starts exploring new markets or technologies.

- Recruit experience, not just enthusiasm. A startup mentor who’s “passionate about helping founders” but has never worked in the industry is about as useful as a lifeguard who’s never seen the ocean.

When we align who we connect with what they need, both ecosystems thrive. Grab a copy of the white paper I have floating around Washington D.C. and the halls of the Texas State government > distinguishing startups from new businesses.

The next time someone tells you their city is “the next Silicon Valley,” ask them one question: Do your programs teach people how to, or connect them with people experienced with?

Ask them of the local accelerator, how many startups are still operating after 5 years? How much more funding have they brought into your ecosystem?

If they stare blankly, congratulations, you’ve just diagnosed the reason their “ecosystem” is really just a networking event with free bagels.

New businesses are built from knowledge; startups are built from discovery. Pflugerville, Texas, last week, teased out the difference in meaningful ways that will help everyone: One learns by doing what’s been done while the other learns by doing what’s never been done.

Until our institutions, investors, and civic leaders grasp that difference, they’ll keep mistaking instruction for innovation.

re: “But when those same playbooks are handed to startups, ventures that live in the world of possibility, not predictability, they misfire. Startups aren’t asking how to do what’s been done. They’re asking what’s possible that hasn’t been done yet.”

You should print this on a poster and sell it. Kudos!

Mark Simchock pushing this a lot more with Founder Institute and in my public policy work. We know it to be true; we need it in practice.

Startups = “What do we believe can be done that 99% of other people think is impossible?”

Anything outside that very narrow scope is simply not a startup. It’s a new business. Nothing wrong with that. We need those as well. But it’s not a startup.

And…..

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/beautiful-lie-venture-capital-tells-why-people-keep-rob-sebastian-uuaic

It really is incredible work that the Pflugerville Community Development Corp. does to support small businesses in the community! They’ve been there since the beginning as we’ve grown Higher Innovation.

It was so much fun moderating the panel on one of my favorite topics, Scaling a business!

Thank you to the panelist and the PCDC for a great time.

You and the team at Higher Innovation are a perfect example of why PCDC’s approach works. They invest in people who actually build things. The “Scaling a Business” panel was a blast to watch come to life; thank you for bringing such grounded, practical insight to the conversation. Pflugerville’s ecosystem is better for having you in it.

This is a beautiful distinction, and I don’t think most people supporting entrepreneurism (in a general sense) understand the difference.

Josh Broward overwhelmingly most don’t. Most don’t want to draw the distinction because it feels critical to say a “new business” is not a “startup” to someone but worse, because people don’t know how to properly make the distinction – it’s the very real risk of being wrong.

Paul O’Brien Awesome post and such an important distinction. Thank you for sharing!

Such an important distinction. Insightful as always Paul O’Brien

This could be a game-changer for smaller cities – investing in the right people can make all the difference when it comes to economic growth.

It’s really quite simple:

1. Startup focus: Multiple Startup Experienced

2. Business focus: Skill & Role Expertise

Too often, Local Startup Programs are run by 2s when they should be limited to 1s

YAY! go Ashely go! Love watching your flourish! <3

Paul O’Brien, I agree with your sentiments. Startups and New Businesses are not the same nor should they be offered the exact same template as resource providers. We were clear that all businesses can’t be viewed and serviced the same. As we continue to support the businesses and ventures in Pflugerville, we will ensure to meet those businesses where they are, not just where we think they are.

Jerry W Jones Jr. Perfectly said. Pflugerville has become a model for exactly that kind of intentional differentiation; meeting founders where they are instead of forcing them into one-size-fits-all programs.

It’s the nuance most regions miss, and why what you’re building in Pflugerville deserves national attention. Grateful to be part of helping tell that story.

Paul O’Brien Couldn’t agree more — this distinction between how-to and experienced-with is critical. The right kind of support makes all the difference between small business growth and true innovation. Grateful to have shared that stage and to keep building bridges that make ecosystems work smarter.

Appreciate that, Robert, you brought exactly the kind of perspective that proves the point. The conversation only works when practitioners like you show how experienced-with changes outcomes in practice. Grateful we had the chance to share that stage and keep building the kind of ecosystem where both business growth and innovation can thrive side by side.

Lots of universities talking theory not how to build grow fund strong teams boards…especially Eu universities

This line is often blurred in my experience. A disservice to everyone involved. This is a step in the right direction!

Kyle Barrios Right? When the lines don’t blur, don’t blur them.

Love this Paul. I talk a lot about the value of ‘been there, done that’ for startups (which is largely & often missing from ‘startup’ economic development programs)…but hadn’t juxtaposed that against the ‘how to’ small business mindset. Process vs. possibility. Well said!

Andrew Steele I find I’m increasingly pushing out investors too; if you haven’t been in startups, odds are slim, that you should be deciding what’s a worthwhile use of capital.

Paul: Thanks for writing this thought-provoking piece! Please allow me to interpret your thoughts through my own lens. It appears that both the new business and startup are in need of knowledge. Therefore, permit me to respectively substitute “instruction” and “facilitation” for “how to” and “experience with.” Instruction explains to a learner how to do something that’s relatively clear. Facilitation guides the learner through a complex process. The use of “facilitation” also avoids the knotty matter of “experience” which in some cases can be a benefit or a hinderance.

Venture With Vision

Steven, I can get behind that though I’d question is people who haven’t been involved in startups can capably facilitate working through a methodology

Not so..not all US eu cities support ceos founders growth cos..10 12 in US few in eu

Thomas Puff, Esq. Not sure I’m following you but I would point out founder != Entrepreneur != CEO

Paul O’Brien yes not all US eu cities support ceos founders growth cos..maybe 10 12 in US…few in eu

It was great to feel the entrepreneurial energy and join my fellow panelists Paul O’Brien, Robert Pieroni & Ashley Ciccel at this impactful event, thank you for organizing Adam Maxon! cc Adam Rosenfield

heck yea! Glad Adam Maxon made it happen!

Such a powerful panel to close out Venture Fest! The conversation and energy you all brought truly captured the spirit of entrepreneurship. Thank you for being part of it and helping make this final day such a success!

Adam Maxon thank you for saying that, it was a pleasure