Most of the articles you read about venture capital, and getting funded, are focused on the positive outcome – finding, meeting, and pitching the VC. Let’s take a look at a startup from the other perspective – how to avoid a “no.”

If an investor takes a shine to you, they’re going to go through what’s called Due Diligence. Begging a question from your perspective – in building your venture, can you plan according to typical red flags for investors and overcome their objections before they have them? Simply put, is there a list of things that always give investors pause? Things to ensure you overcome.

What is Due Diligence?A measure of prudence, responsibility, and diligence is expected from, and ordinarily exercised by, a reasonable and prudent person under given circumstances. Thus in operating an entity, founding a startup, a potential investor will gather necessary information on actual or potential risks involved in the investment opportunity. It is the duty of each party to confirm each other’s expectations and understandings, and to independently verify the abilities of the other to fulfill the conditions and requirements of the agreement.

Are you prepared to overcome an investor’s expectations? Considering that their expectations start and end with a return on their investment, what are some of the most common red flags that give potential investors pause?

Let’s a take a stab…

- Are the founders investing their own money in the venture? If not, why would anyone else?

- Are there an exceptional number of investors and/or industry inexperienced investors who have a sizable share? That can signal that raising earlier funding was particularly difficult for some reason or that there are investors involved who might burden the focus of the venture.

- Mistaking customer validation for market validation. Potential and existing customers DO NOT validate that you can achieve and maintain a share of the market. Do you have market validation?

- Gaps in the team – at least, essentially, three areas of focus: resources, building, and the market. As I’ve put before, the Butcher, the Baker, and the Candlestick Maker.

- “There is no competition” or “this is a unique idea” – sure it is.

- Lacking basic marketing/KPI oriented elements: capable site, Analytics, appropriate social media, some Adwords (or otherwise) capably tested, etc.

- Clearly inexperienced Go to Market plan. References to areas of focus being broad or generic and not distinctly applicable. Such as stressing: SEO, Content Marketing, PR/Press Release, Sales – that’s not a plan; that’s standard operating procedure for any organization

- Narrow focus in a broad market – only having partners/traction in one city, only being iOS for a mobile, only knowing one target when others are clearly applicable, etc.

- Excessive debt and/or stated intention to get the founders paid

- Early investors having no further interest. Even if only so as to make the right connections and provide experience/advise to further success, one can expect that anyone invested in the business continues to be so, unless something is wrong.

- Sole proprietorship or family focused founding / executive team. Investors seek exits – sole proprietors and families tend to keep a business in perpetuity.

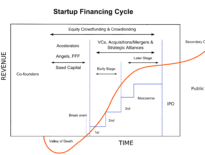

- Suggesting unrealistic growth or projections. Likewise, unrealistic valuations. YOU WILL NOT GROW UP AND TO THE RIGHT.

- Neither a Board of Advisors nor Directors, equity allocated, involved. Your team is not limited to your employees.

- Incomplete financials

- Controlling or opaque founders. Can we look into everything? Do we know all the other investors? Is the team open to change? Loosely related things such as major foreign investors – whom aren’t necessarily unknown/silent but have different circumstances/considerations that may factor in

- IP or ownership issues. Likewise but contrary, expecting VCs sign NDAs

- Highly regulated markets or industries potentially so. Might the industry cause a problem and if so, are you aware of that possibility and have you addressed the challenge?

An exhaustive list? By no means! But consider as you endeavor that a potential investor will conduct due diligence and the process starts even before you have a conversation with them. Working to overcome the causes for concern might be a better approach to getting funded than perfecting your pitch.

As an IP lawyer, I highly stress to clients, whether we’re representing the startup or the investor, they need to make sure the contracts are done properly. There needs to be proper formation agreements, employment agreements, independent contractor agreements, assignments, licenses, NDAs, etc. in place to protect any IP allegedly owned by the company and deal with many other potential issues. Depending on the industry, this can be as important as any IP filings. We’re constantly doing clean up or raising red flags because of this.

Yep! Great one Kirk. Tips on getting this done efficiently? How might startups make sure they’re off the right start even if not completely buttoned up (given the potential cost of doing so)?

This is helpful Paul! Would love to hear more on a few of these. Particularly if working full-time on an idea for 1+ year without getting paid is equivalent to investing your own money in the idea, how market validation is different from customer validation, and narrow focus in a broad market. Especially that last one seems a little counterintuitive to other advice that says focus, focus, focus on a small market first. Yesterday I listened to one of the founders of Favor talk about their focus on hungover college students in one zip code then the founder of Wealthfront talk about their focus on technical employees at Facebook. Obviously both saw potential in the broader market, but these were the target early on…

Great questions, big topics… perhaps we should do an event? 🙂

Does working full time with no income the equivalent as investing your own money? Yes… and no. The question of investing one’s own money is a way of seeing where the founders prioritize spending their own money. If you won’t spend money on it, why should anyone else?

Customers vs. Market stems from the oft-quoted customer service adage, “Customers are always right” – except most of the time. The market is comprised of competitors, partners, thought leaders/media voices, and more. Having paying customers doesn’t remotely validate that a startup has figured out how to grow, compete, and thrive.

The point about a narrow focus in a broad market is related… if you’re building a web service and your traction is Austin based customers and partners, you’ve not proven anything other than that you can build something people familiar will buy.

It’s not a question of the focus (or lack thereof), it’s a red flag. It raises questions. IF only focused on college students in one zip code – what are you trying to prove and learn? WHY focused on technical employees at Facebook?

If the startup has been successful in that focus but it’s because they know it and haven’t figured anything else out – red flag! If the startup is focusing there because they’ve determined that it’s more valuable, accessible, defend-able, etc. or that they’re at the stage of trying to learn something (that isn’t already well known to others), great!

Yes, I definitely have a few tips, but they can get lengthy; I’ll give a few pointers here though. I’ve taught seminars on how to manage legal costs. A little background, I’ve worked as in-house counsel for a big tech company and managing costs was a big part of the job; fired many law firms for not complying with billing requirements.

In general, I advise clients never to give an attorney an open checkbook. I wouldn’t do that with a mechanic or a home contractor, don’t do it with an attorney either. Get a quote for the work you want done, and then get an agreement, in writing, that states the attorney is not allowed to bill beyond the pre-approved budget or flat fee. Attorneys love giving the excuses of not knowing how much time something will take, etc. but it’s almost all BS except for complex issues. An experienced attorney will have a good idea of how much time certain tasks will take, and you should expect to hold them to it. Many attorneys will not like this concept of having a cap limit on their billing; walk away from anyone not willing to do so.

I also recommend shopping around, many attorneys set up startups with the formation and agreements they need for a flat fee; I don’t do this kind of work, but my clients tell me $2,500-$5,000 for a simple partnership setup is common. Unless you have an odd entity structure or complex arrangement, I would expect it should not take more than 10 hours of attorney time to set up a company with formation agreements, employment agreements, and contractor agreements considering it is mostly done from templates. However, beware of anyone using only templates, as they should be customized for the startup’s individual needs.

For a startup to be off to the right start, they need contracts. There’s just no way around this, but they can be done cost-effectively. If there is anything inventive (e.g. patentable – devices, software, systems) or creative (e.g. copyrightable – designs, computer code, literary works, artwork, graphics, etc) being done, the company absolutely needs a contract to have ownership of those things. One common misconception is that the “work made for hire” copyright law will protect a company; it usually does not and is very narrow and hard to prove, a written contract is much cheaper on the front end than trying to prove work made for hire later when a critical meltdown is happening. Anything created prior to a written agreement in place is likely not owned by the startup and a later assignment agreement will need to be executed, which brings in a lot of other potential problems and costs.

I’m sure business attorneys and employment attorneys could also make a long list of why a startup should have contracts done properly from the start. Hope this helps.