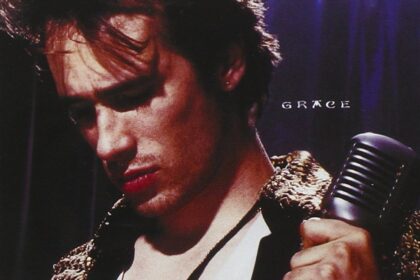

There’s a thought Jeff Buckley once shared, half-interview, half-confession: “Grace is what matters in anything. It keeps you from pulling the trigger too soon. It keeps you from destroying things too foolishly; it sort of keeps you alive and keeps you open for more understanding.” You could hang that on the wall of every entrepreneurs’ office and still not appreciate the truth of it.

Buckley wasn’t preaching spirituality. In the same breath, he’d shrug, “I’m not a god or a saint or a genius, I’m just a musician,” grounding his idealism in mortal craft. That humility, the artist refusing the myth, is what most founders forget when they start believing their own pitch decks.

Because for all our talk of innovation and disruption, most entrepreneurs misplace grace. They understand speed, iteration, capital, even charisma, but grace is too often lost in our pursuit of success by the book. That’s why most innovation sounds like noise: all pitch, no resonance.

The artist who recorded Grace was, by every measure, an entrepreneur. He wasn’t born into privilege or industry access. He built his audience from a handful of patrons in a coffeehouse so small that a sneeze could interrupt a song. His “startup” wasn’t a company; it was the art of learning in public; his guitar, his voice, and the terrifying honesty of doing it in front of real people who didn’t owe him applause.

Buckley’s path, in short, is the playbook of creation itself. Not the sanitized, PowerPoint version of creativity that universities and pitch deck templates like to canonize, but the kind of creation that leaves skin on the floor.

I’m writing this because someone whose work is as kind and passionate as I try to be, suggested exploring in startups an artist rather than the film or music analogies I tend to draw. When Eric Alper coincidentally shared that question, I knew the song that immediately spoke to me; fitting, because “Hallelujah” once wrecked me, in a room full of people who didn’t expect a song to do what data rarely does: break defenses, align values, and move people to act. Product Market Fit for the human condition; let’s take a look at how an artist changes lives and inspires entrepreneurs.

Article Highlights

The Workshop Before the Record Deal

Before the studio, there was Sin-é, a café on New York’s East 4th Street. Jeff played there constantly: covers, originals, sometimes both in the same breath. “You can’t create without the crowd,” he said in a 1994 interview. “You learn to surrender to it, or it kills you.”

Sin-é was the founder’s prototype lab. A minimal viable product, live and unfiltered. He tested his material against real customers, the kind who paid for coffee, not tickets. Every song was a sprint. Every set, a demo day.

He’d slip from Edith Piaf to Van Morrison, from “Strange Fruit” to his own “Mojo Pin.” That wasn’t genre confusion, it was iteration. The data of emotion. While founders measure click-through rates; artists teach us that you should be measuring the intake of breath before a room goes silent as you begin.

And unlike most startup programs, Buckley didn’t pivot because a mentor told him to. He pivoted because the feedback loop of humanity guided.

“I would rather play two notes in front of real people than a thousand behind a wall,” he told an interviewer. That wall, between performer and listener, creator, and customer, is exactly what separates invention from noise. Buckley never let the wall form.

The Product Was the Performance

When Grace arrived in 1994, it didn’t sound like anything else on the market. Columbia Records wanted another pop record. Buckley delivered something unclassifiable: ethereal, furious, devotional.

The title track, “Grace,” isn’t a song about salvation, it’s about surrender to what you can’t control. “There’s the moon asking to stay,” he sings, “Long enough for the clouds to fly me away.” That’s not melancholy; that’s acceptance, the kind that fuels every founder who knows that what they’re building might just outlive them.

He understood what startups call opportunity cost. Buckley left Grace untouched after release. He didn’t chase radio edits, didn’t remix it to fit the market. He let it stand as it was, imperfect, alive. And what did the market do?

It ignored him.

His mother later said he came home bewildered but unbroken, “He believed in Grace the way a scientist believes in a theorem because he’d proven it night after night.”

Rolling Stone gave the album a polite shrug.

Critics complained it was “too emotional” (As if that were a vice). Years later, the same publications canonized it as one of the greatest albums of all time. Innovation, as usual, was early to its own applause.

Entrepreneurs, take note: if the critics get you too soon, you’re not innovating, you’re optimizing.

Iteration as Category Design

Buckley’s rendition of Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” is not a cover. It’s an acquisition. He took an undervalued intellectual property and reengineered it until it became synonymous with his name. That’s not imitation, it’s category creation. If you’re not familiar with the song, you might know what Johnny Cash did with Nine Inch Nails’ Hurt, both will bring you to emotions we should all feel.

The song itself is a masterclass in market adoption. Cohen’s original was literate and restrained; Buckley’s was carnal and celestial at once. He once described it as “not a homage to a worshipped person, idol or god, but the hallelujah of the orgasm. It’s an ode to life and love” That duality (spirit and skin) is what made it viral long before virality was a metric.

And because Buckley poured himself into someone else’s creation, Cohen’s version finally found new audiences decades later. The ripple lifted all boats. That’s how great founders operate: build something so good that even your competitors get better because of it.

Water Takes Us Into the Myth of Risk

A friend recalled that days before his death, Buckley scribbled in his notebook, “There’s no end to love, only the end of understanding.” He’d been writing new material, planning sessions with his band, talking about redemption and rebirth. The future was opening wide.

In 1997, while working on his follow-up album, My Sweetheart the Drunk, Buckley drowned in the Wolf River, a tributary of the Mississippi. No drugs. No melodrama. Just a man, fully alive, singing Zeppelin’s “Whole Lotta Love” under the Mississippi Suspension Bridge as the water took him.

It’s haunting to remember his own words from “Dream Brother”:

“Don’t be like the one who made me so old / Don’t be like the one who left behind his name.”

The song was a plea to his friend not to repeat the abandonment of fathers and sons, but it reads now as prophecy; a man trying to break inheritance and fate, swept instead into both.

People love to turn that into a metaphor, but it isn’t tragedy, it’s a parable about risk. Creation doesn’t happen in safe harbors. You wade in, knowing the current can pull you under. Artists and entrepreneurs share that blind faith: that immersion itself is the point, that control is an illusion, that the only sin is never stepping into the water. Buckley once said, “Music comes from a primal place, it’s the sound of the river in me.” He understood the current as creation itself: restless, alive, and sometimes merciless. To enter that flow is to accept that what moves you may also undo you.

When the market takes you down, it’s not a failure of vision. It’s proof that you played where others watched.

The Business of Feeling

Buckley didn’t sell music; he sold vulnerability. That’s the part the world still doesn’t understand about him or about innovation. You can’t systematize what you’re unwilling to feel.

He could have been a chart-topping pop star, but he turned down collaborations that didn’t align with his values. He refused shortcuts, refused to repeat himself. “I don’t want to be remembered for one thing,” he said. “I want to keep being born.”

That’s entrepreneurship. The rebirth, the perpetual discomfort of reinventing something that works because stagnation feels like death. Most founders don’t fail because the market changes; they fail because they don’t.

Every artist like Buckley is an R&D department for the soul. They prototype emotion. They run experiments on meaning. They find language for feelings the rest of us only sense. And when the world finally catches up, we call it timeless. He taught, “Be awake enough to see where you are at any given time and how that is beautiful,” reminding creators that awareness, of the present, not the promise, is the only defense against the machinery of ambition.

The Founder’s Grace

Here’s the lesson that everyone, from startup accelerators to civic leaders, keeps missing: innovation isn’t an act of intellect, it’s an act of empathy. It’s feeling before it’s thinking. It’s believing before seeing, not seeing to believe.

Jeff Buckley lived that truth. He taught through art what business schools still can’t teach through frameworks: that creation is the intersection of mastery and surrender.

He never scaled. He never raised a round. He built something better: proof that even in a world addicted to growth, depth still compounds.

When he sang, “Love is not a victory march, it’s a cold and it’s a broken hallelujah,” he was describing not heartbreak but the entire process of creation. The brokenness is the work. The hallelujah is what we make of it.

To the founders, investors, and creators who still believe you can spreadsheet your way to inspiration: stop mistaking control for competence. Go play your Sin-é. Test your song. Listen to your audience breathe.

And when you find that moment, the hush between notes where meaning happens, don’t optimize it. Don’t brand it. Don’t pivot. Have the grace to let it live.

Because that’s what Jeff Buckley understood better than most entrepreneurs ever will: creation isn’t about what lasts forever. It’s about daring to make something worth remembering at all.

“You and I will rise up all the way,” he sang in “Lover, You Should’ve Come Over.”

Maybe that’s the real covenant between artists and entrepreneurs: to rise together, not by escaping risk, but by daring to create despite it.

Creation done openly will always age better than perfection done in silence. Buckley just had the nerve to live that lesson before it became fashionable.

Mark Leaning, PhD beautiful thought.